Physicists propose a new way to spot supermassive black hole pairs

Galaxy mergers should leave behind tight pairs of supermassive black holes, but few have been confirmed.

Edited By: Joshua Shavit

Edited By: Joshua Shavit

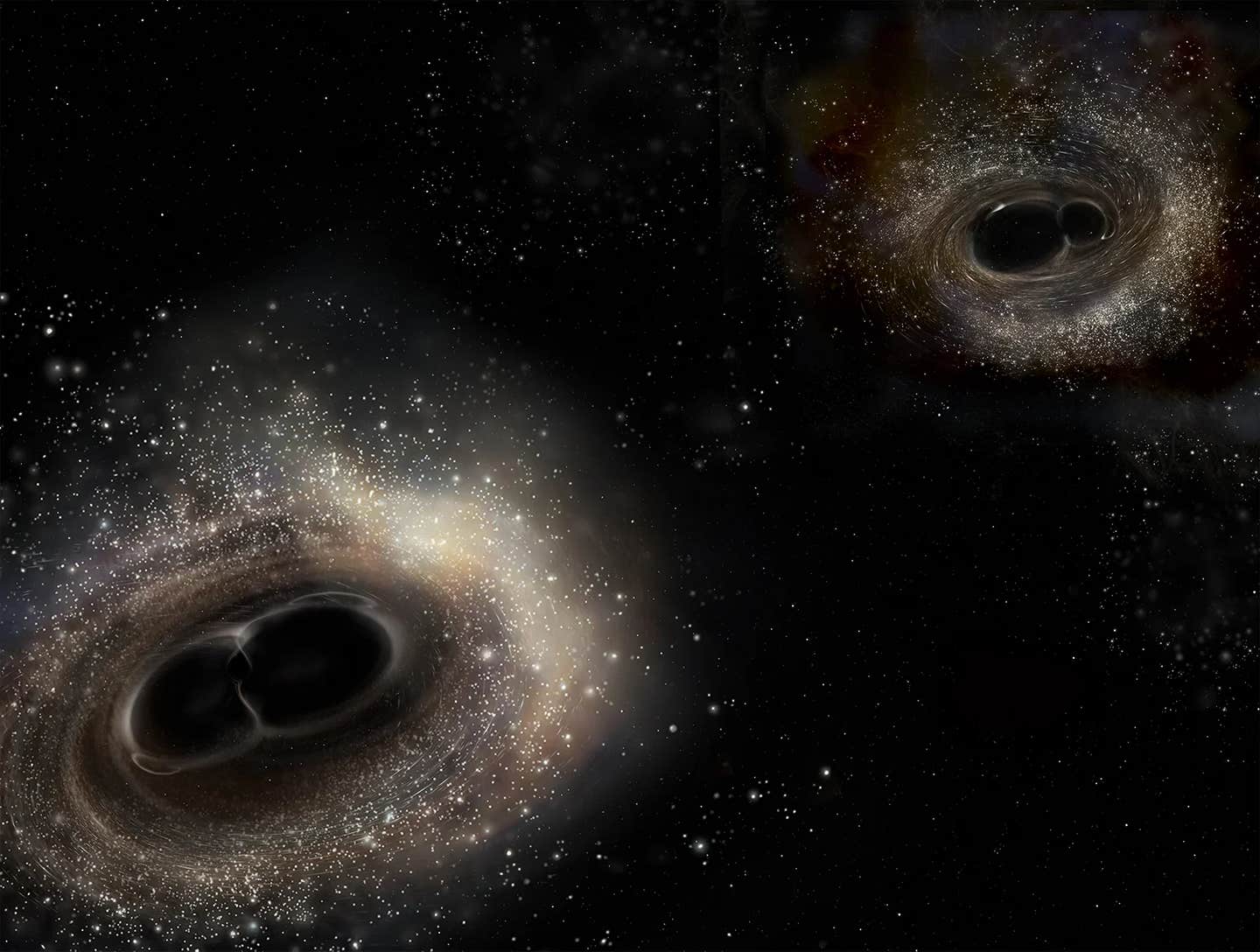

A new idea suggests hidden supermassive black hole pairs could reveal themselves through repeating, magnified flashes of starlight. (CREDIT: LIGO/Caltech)

Supermassive black holes rarely travel alone. Most large galaxies hide one at the center, and when galaxies collide, the two central black holes can end up bound together. Astronomers have seen plenty of wide pairs. The tighter ones, the kind that spiral inward and eventually merge, have been much harder to pin down.

Researchers at the University of Oxford and the Max Planck Institute for Gravitational Physics (Albert Einstein Institute) think the missing systems may be giving themselves away anyway, in brief, repeating flashes of starlight. In a paper published today in Physical Review Letters, they argue that a tight supermassive black hole binary could act like a moving magnifying glass, repeatedly boosting the light from individual stars in the same galaxy.

“Supermassive black holes act as natural telescopes,” said Dr Miguel Zumalacárregui from the Max Planck Institute for Gravitational Physics. “Because of their enormous mass and compact size, they strongly bend passing light. Starlight from the same host galaxy can be focused into extraordinarily bright images, a phenomenon known as gravitational lensing.”

A Flash That Comes Back

With a single supermassive black hole, the most extreme lensing needs a near-perfect alignment: a star almost exactly behind the black hole from our point of view. That makes the best events rare and easy to miss.

A binary changes the geometry. Two lenses create more complicated high-magnification zones, including a diamond-shaped structure called a caustic curve. If a star sits in the wrong place behind that pattern, its light can spike sharply.

In theory, the magnification can blow up to infinity for a point-like source. Real stars have size, so the peak gets capped by the star’s surface.

“The chances of starlight being hugely amplified increase enormously for a binary compared to a single black hole,” said Professor Bence Kocsis from the University of Oxford’s Department of Physics and a co-author of the study.

And the key twist is motion. A binary does not sit still. It orbits, and as it radiates gravitational waves, it loses orbital energy. The separation shrinks over time, and the orbit speeds up.

Not Random, Not One-Off

Graduate student Hanxi Wang, who works in Professor Kocsis’ group, led the study. “As the binary moves, the caustic curve rotates and changes shape, sweeping across a large volume of stars behind it. If a bright star lies within this region, it can produce an extraordinarily bright flash each time the caustic passes over it. This leads to repeating bursts of starlight, which provide a clear and distinctive signature of a supermassive black hole binary.”

That repeat part matters. Lots of things in the sky flicker. A flare that returns on a schedule gives observers something to grab onto.

In the framework laid out in the paper, the bursts also carry a fingerprint. As the binary inspirals, gravitational-wave emission subtly changes the caustic structure. The team argues that this can show up as a modulation in both the timing and the peak brightness of the flashes.

Measure that pattern well enough, and you can back out properties of the hidden binary, including masses and how the orbit evolves.

When a Star Outshines its Galaxy

The paper goes deeper than a simple sketch. The researchers model the binary as two point-mass lenses and track how the caustics move as the orbit tightens.

They estimate that a star in the host galaxy with a radius of 10–10^3 solar radii can be magnified by about 10^4–10^6. For bright stars such as red giants or main-sequence O/B-type stars, they describe how the amplified luminosity could reach 10^6–10^12 solar luminosities.

In other words, one ordinary star, briefly boosted, could look like a powerful central source. The authors note that this does not require gas around the black holes, which matters because “more than 90% of galaxies do not produce an AGN.”

The signal they focus on has a name: quasiperiodic lensing of starlight, or QPLS. In the idealized case they discuss, the rotating caustic can create multiple high-magnification events each orbital period, and the number and shape of peaks can change as the caustic shrinks during inspiral.

Even the duration of a peak has a scale in their estimates. They give a characteristic brightening time of about 16 hours, depending on orbital and source parameters.

Catching it with Real Surveys

All of this only helps if telescopes can spot the pattern in messy, real data. The researchers point to wide-field surveys already operating or coming soon.

They mention the Zwicky Transient Facility, Subaru’s Hyper-Supreme Cam, and future projects including the Vera C Rubin Observatory and the Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope. Rubin, they write, will monitor roughly 2 × 10^10 galaxies over ten years, with time resolution of about days in a single filter. Roman could observe periodic signals with cadence as low as five days, while reaching faint depths.

They also describe ULTRASAT as another time-domain option.

The paper includes rough rate estimates too, using a probability for QPLS and extrapolating to synthetic catalogs. They give a range of 1–50 [190–5000] QPLS sources in systems with periods below 10 [40] years at redshift z < 0.3, scaled by stellar density. They also estimate caustic crossing rates across nearby galaxies that can reach hundreds to far more per year, depending on assumptions.

The authors do not pretend the search will be easy. They flag the need for more realistic light curves that include the star’s own motion. They also point out that gas around a binary could block some images and add extra signatures, complicating interpretation.

Still, the attraction is obvious. “The prospect of identifying inspiraling supermassive black hole binaries years before future space-based gravitational wave detectors come online is extremely exciting,” concludes Professor Kocsis. “It opens the door to true multi-messenger studies of black holes, allowing us to test gravity and black hole physics in entirely new ways.”

Practical Implications of the Research

If this works, it gives astronomers a new way to find tight black hole pairs without relying on a bright, gas-fed active galactic nucleus. That could widen the census of binaries in quieter galaxies, where traditional methods struggle.

It could also create an “early warning” channel for future gravitational-wave detections. The paper describes cases where the light-curve modulation becomes prominent before a system enters the band of planned space-based detectors like LISA and TianQin, and it discusses how combining an electromagnetic detection with gravitational-wave searches could strengthen multi-messenger studies.

Even when gravitational waves arrive later, the earlier light signal could help observers know where to look, and what kind of system to expect.

Research findings are available online in the journal Physical Review Letters.

The original story "Physicists propose a new way to spot supermassive black hole pairs" is published in The Brighter Side of News.

Related Stories

- Three black holes light up at once in rare three-galaxy collision

- Astronomers capture first-ever image of two black holes orbiting each other

- Two new black hole collisions confirm Einstein’s theory with record precision

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.

Joseph Shavit

Writer, Editor-At-Large and Publisher

Joseph Shavit, based in Los Angeles, is a seasoned science journalist, editor and co-founder of The Brighter Side of News, where he transforms complex discoveries into clear, engaging stories for general readers. With vast experience at major media groups like Times Mirror and Tribune, he writes with both authority and curiosity. His writing focuses on space science, planetary science, quantum mechanics, geology. Known for linking breakthroughs to real-world markets, he highlights how research transitions into products and industries that shape daily life.