Radio telescopes reveal the final years of a rare exploding star

Astronomers detected radio waves from a rare Type Ibn supernova for the first time, uncovering how a massive star shed material in its final years.

Edited By: Joshua Shavit

Edited By: Joshua Shavit

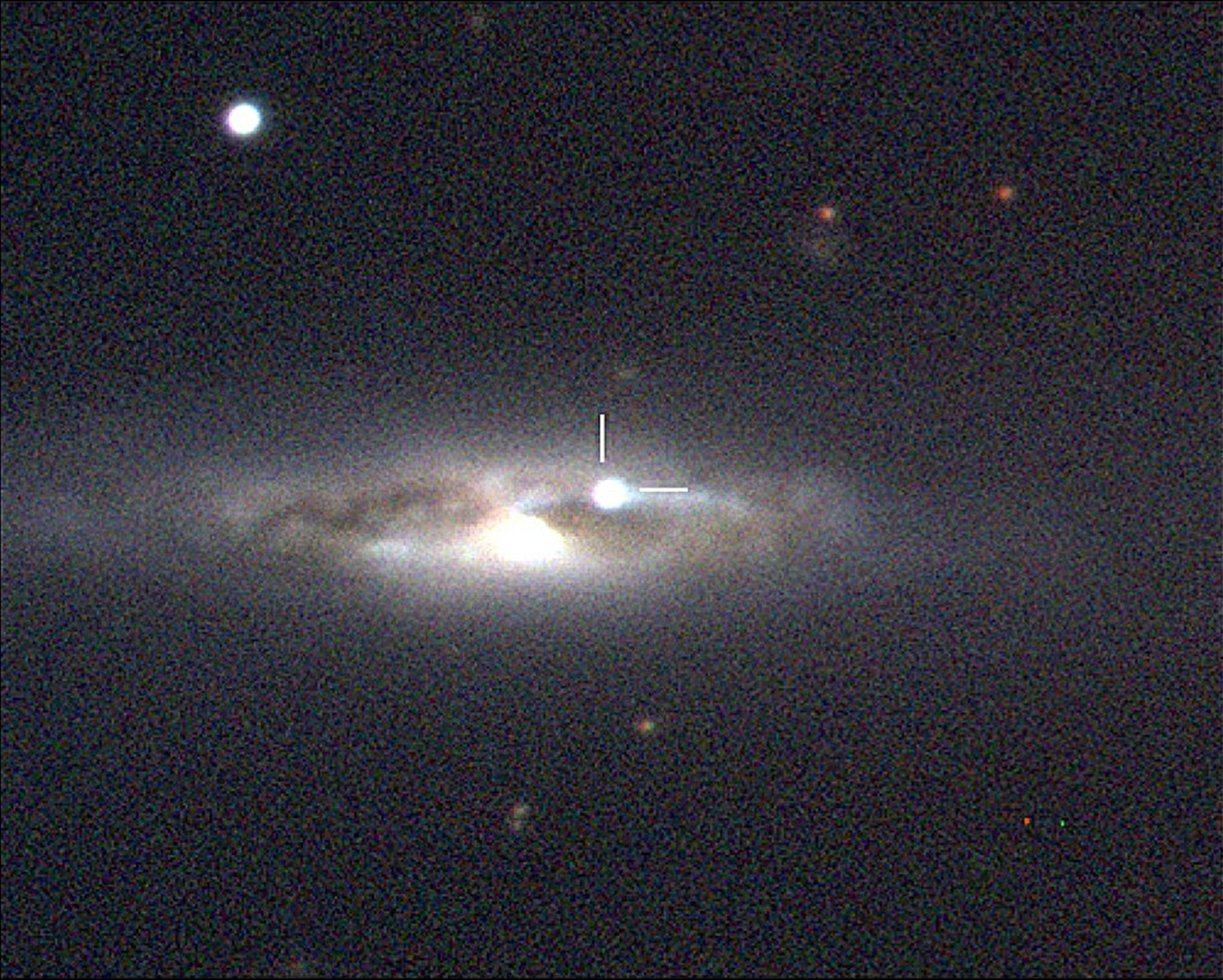

Composite gri image of NGC 4388 showing SN 2023fyq, captured by the Las Cumbres Observatory on August 11, 2023. White tick marks highlight the supernova’s location. (CREDIT: Dong et al., 2024)

Astronomers have discovered the first radio signals from a unique category of dying stars, called Type Ibn supernovae, and these signals offer new insights into how massive stars meet their demise. This new study provides an unprecedented level of detail about the last stages of stellar evolution.

“The radio observations show us what the last ten years of a star’s life looked like, and how much it lost in mass during that time,” explains Raphael Baer-Way, a third-year PhD student studying astronomy at the University of Virginia, who led the research team working at the NSF’s Karl G. Jansky Very Large Array in New Mexico, along with several other radio telescopes tracking the first few months of faint radio emission from supernova SN 2023fyq.

“Our observations allowed us to experience the last decade of the star’s life leading up to its explosion in real time, a true time machine,” says Baer-Way. “Because we were able to detect the radio emission from SN 2023fyq, we will be able to learn more about the dying star’s mass-loss history and other important details about the star.”

Rare Supernovae And Rapid Fading Signals

Type Ibn supernovae are formed from stars that shed substantial amounts of helium-rich gas prior to exploding. The material ejected from these stars records information about their last moments of life, and when the supernova shock wave strikes that material, it creates radio waves that optical telescopes cannot observe.

Type Ibn supernovae are one of the rarest types of supernovae, representing probably less than 1 per cent of all Type II core-collapse supernovae. They are unique for their lack of hydrogen and the presence of narrow helium emission lines in their optical spectra. These characteristics originate from a dense gas neighborhood close to the explosion site near the star.

The characteristics of these explosions diminish rapidly. Their brightness decreases at a rate of 0.1 mag per day during the first month after the explosion, a rate faster than the majority of supernova types. This high rate of decline makes it difficult to conduct detailed studies of these supernovae, particularly at wavelengths beyond the visible spectrum.

A Fortuitous Explosion Close To Home

A unique opportunity for study was available when SN 2023fyq exploded in mid-July 2023. This explosion occurred near NGC 4388 and is approximately 18 million light-years from Earth. It was observed both before and after its explosion. Observations in optical wavelengths indicated an outburst signature that lasted over 1,500 days, indicating a previously unstable system.

Due to the distance of the explosion from the active core of NGC 4388, astronomers are studying the exploding star without interference from the galaxy’s active galactic nucleus. Pre- and post-blast spectra confirmed the total destruction of the star.

"We began observing SN 2023fyq with radio telescopes approximately 58 days after its explosion. Early observations showed no radio emission from the supernova. Later, a radio signal was detected at higher frequencies. This easily distinguishable signal then faded over the next few months," Baer-Way told The Brighter Side of News.

Tracing Mass Loss Through Radio Waves

When a supernova explodes, it produces radio emission as high-speed electrons move through magnetic fields while shock waves from the explosion collide with dense material. The dense compression of ionized gas initially blocks radio signals from escaping the supernova. This occurs as a result of free-free absorption by the gas. When the shock propagating outward through the ionized material expands further, the radio waves are finally able to escape.

The researchers were able to reconstruct how a massive star shed mass before it exploded by producing radio light curves. These light curves show that the star lost around 0.004 solar masses per year at a steady rate over the final one to three decades leading up to the explosion. This rate is significantly larger than what is seen with typical stellar winds and suggests that the star experienced an intense period of mass loss.

The material ejected from the star extended out to a distance of approximately 1.4 × 10¹⁶ centimeters from its original position. The radio light curve data also showed a sudden decrease in radio-emitting flux around 525 days after the explosion occurred. This indicates that at some distance from the supernova site, there must have been a very low density of gas.

Evidence For A Binary Star System

The star did not experience consistent or steady mass loss throughout the decades. Rather, it likely went through a brief burst of mass loss just a few years prior to exploding, with relatively calm or steady mass loss during earlier stages.

Baer-Way stated that losing a mass similar to what was observed would require two stars orbiting one another through gravitational binding.

The data indicate that the progenitor of the supernova was most likely part of a binary stellar system. This finding is consistent with optical observations showing that one of the stars in the current binary system is likely a low-mass helium supernova-like star with a mass of approximately three times that of the Sun, or a neutron star companion. Either unstable mass transfer or a merger of stars likely led to the sudden shedding of gas.

X-Ray Silence And Broader Implications

Data from both the Swift X-ray Observatory and the Chandra X-ray Observatory detected no X-ray emissions at any point throughout the supernova event. This absence is important. The continued presence of dense gas around the supernova site would have resulted in ongoing X-ray emission. Its absence therefore supports the idea that the remnant of the exploding star formed a shell-like object rather than a long-lasting stellar wind remnant.

Professor Maryam Modjaz of the University of Virginia, an expert in massive star deaths, noted, “Raphael’s paper has opened up a new window to study supernovae by allowing us to more effectively point radio telescopes significantly earlier than would have otherwise been assumed, to catch these transient radio signals associated with massive stars before they explode.”

Implications of the Research

The data support the premise that radio telescopes can reveal far more information about the death of a star than can be obtained from optical light alone. The ability to trace timelines of mass loss many years before a supernova explosion enhances understanding of how massive stars evolve and ultimately explode.

The research also highlights the significant role that binary stellar systems can play in shaping how a star dies. These insights will improve scientific models of supernova behavior, the chemical enrichment of galaxies, and the origins of neutron stars and black holes. As radio telescope surveys expand, it is likely that more supernovae will be discovered with previously unknown histories leading up to their explosive ends.

Research findings are available online in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

Related Stories

- JWST detected a supernova from the dawn of the universe

- 10 billion-year-old supernova sheds new light on cosmic expansion and dark energy

- Fist-of-its-kind supernova offers rare look into the explosive death of a star

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.

Joseph Shavit

Writer, Editor-At-Large and Publisher

Joseph Shavit, based in Los Angeles, is a seasoned science journalist, editor and co-founder of The Brighter Side of News, where he transforms complex discoveries into clear, engaging stories for general readers. With vast experience at major media groups like Times Mirror and Tribune, he writes with both authority and curiosity. His writing focuses on space science, planetary science, quantum mechanics, geology. Known for linking breakthroughs to real-world markets, he highlights how research transitions into products and industries that shape daily life.