Rainfall became irregular during Earth’s hottest periods, raising global warming concerns

Study of the early Paleogene finds rainfall grew less reliable in extreme heat, with long dry spells and intense downpours.

Edited By: Joseph Shavit

Edited By: Joseph Shavit

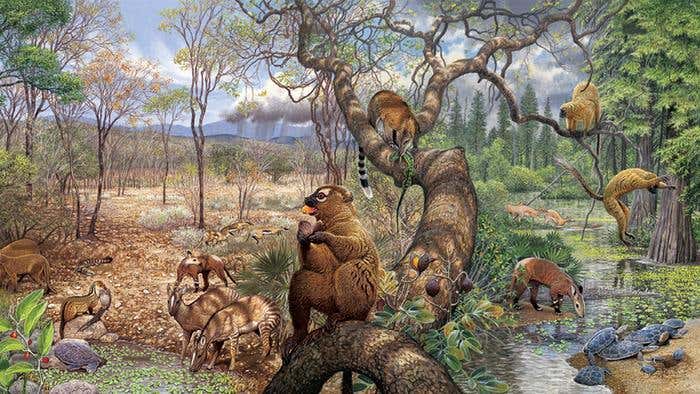

A Nature Geoscience study finds that in one of Earth’s hottest eras, rain often arrived in bursts, not steady seasons, drying many mid-latitudes. (CREDIT: U.S. Geological Survey)

The climate record holds some of its best warnings in stone, soil, and leaves. In a new study, scientists from the University of Utah and the Colorado School of Mines looked back to one of Earth’s hottest eras to see how rain behaved when the planet ran far warmer than today. What they found challenges existing knowledge regarding climate change and rainfall.

The research examines the early Paleogene, roughly 66 to 48 million years ago. During that stretch, atmospheric carbon dioxide levels sat about two to four times higher than modern levels. The team used that deep-time heat as a test case for how a hotter world can reshape the water cycle.

Instead of asking only how much rain fell in a year, the researchers focused on something that often gets missed. They asked when rain fell and how steady it was across seasons and years. Their conclusion is blunt. Under extreme warming, rainfall can become far less reliable, even in places that are not deserts.

A Hot Earth That Rewrote the Rules

Many people have heard the idea that wet places get wetter and dry places get drier as the climate warms. Thomas Reichler, a professor of atmospheric sciences at the University of Utah and a co-author of the study, said the assumption has strong physical logic behind it. Yet the paleoclimate evidence told a different story.

“There are good reasons, physical reasons for that assumption,” Reichler said. “But now our study was a little bit surprising in the sense that even mid-latitudes regions tended to become drier.”

That drying did not always come from a simple drop in total rainfall. The bigger shift involved timing. The team found signs that rain fell in bursts, with long dry spells in between. In that kind of pattern, land can look dry even if the sky still delivers plenty of water over a full year.

Reichler also pointed to what this rhythm does to ecosystems. “It has to do with the variability and the distribution of precipitation over time,” he said. “If there are relatively long dry spells and then in between very wet periods, as in a strongly monsoonal climate, conditions are unfavorable for many types of vegetation.”

Following Clues Instead of Rain Gauges

No one can measure a rainstorm from 50 million years ago with an instrument. So the team relied on proxies, which are climate hints preserved in the geologic record. The Colorado School of Mines researchers examined plant fossils, ancient soils, and river deposits to reconstruct past conditions. Reichler and graduate student Daniel Baldassare handled the climate modeling.

Plant fossils can act like a time capsule for moisture and temperature. “From the shape and size of fossilized leaves, you can infer aspects of climate of that time because you look at where similar plants exist today with those leaves,” Reichler said. “So this would be a climate proxy. It’s not direct measurement of temperature or humidity; it’s indirect evidence for climate of that time.”

Landforms add another layer of evidence, especially old river channels. Reichler explained how rivers react when rain arrives in extremes. “When there is intermittent, strong precipitation then followed by long periods of drought, that precipitation is forming the riverbed in different ways because there’s very high amounts of water flowing down and carving it out or transporting the rocks much more vigorously than were it a little drizzle every day,” he said.

These reconstructions come with uncertainty, and Reichler emphasized that point. Still, the team treated them as the best available window into how rainfall behaves under extreme warming, especially when paired with climate model results.

What the Early Paleogene Looked Like

The study targets a world that feels almost alien compared with modern life. The early Paleogene began after the sudden demise of the dinosaurs and unfolded during the rise of mammals in terrestrial ecosystems. In Utah, the period also links to the formation of notable landscapes. The hoodoos of Bryce Canyon and the badlands of the Uinta Basin trace back to deposits from that era.

The early Paleogene also includes a dramatic warming episode known as the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum, or PETM. The study describes this as a time when heat levels rose to about 18 degrees Celsius, or 32 degrees Fahrenheit, warmer than they were just before humans began releasing greenhouse gas emissions into the atmosphere. Some scientists view that climate as a possible worst-case comparison for future change.

Yet the study’s message goes beyond one event. The researchers found that irregular rainfall patterns began millions of years before the PETM and lasted long after. That long duration suggests the climate system can settle into a new rainfall style once it crosses certain thresholds.

A Rainfall Pattern Marked By Extremes

The team’s key finding is not simply “more rain” or “less rain.” It is about how rain arrived.

They found evidence that rainfall under extreme warmth became far more variable. Downpours hit hard, and dry stretches stretched longer. In other words, precipitation became less regular.

The researchers concluded that polar regions were wet during the Paleogene, and they may have experienced monsoonal patterns. At the same time, many mid-latitude regions and continental interiors became drier overall.

This result matters because it pushes back on an overly neat picture of rainfall change. Even places you might expect to stay comfortably watered can shift toward longer dry periods, especially in the middle latitudes. The study ties that risk to shorter wet seasons and longer gaps between rain events.

The team also compared proxy-based reconstructions with paleoclimate model simulations. Their analysis suggests that today’s models underestimate how irregular rainfall can become when warming reaches extreme levels. That gap matters because people often plan around averages, not around whiplash.

Practical Implications of the Research

This research shifts attention from yearly rainfall totals to rainfall reliability. In daily life, you feel the difference between steady seasonal rain and a handful of violent storms. A region can post the same annual total but still suffer. Crops can fail during long dry spells, and floods can follow when rain finally returns in intense bursts. Water systems can also struggle when wet seasons shrink and dry gaps widen, even if the long-term average looks acceptable.

The findings also give scientists a tougher benchmark for climate models. By using proxies from plant fossils, soils, and river deposits, the team highlights patterns that models may not fully capture under extreme warming. That creates a clear research goal. Future modeling work can aim to reproduce the Paleogene’s stop-and-start rainfall. If models can match those ancient patterns, planners can trust projections more when making decisions about drought risk, flood control, and ecosystem stability.

Finally, the study offers a caution about thresholds. The irregular rainfall patterns began well before the PETM and continued long after. That suggests the climate can lock into a new mode once conditions shift far enough. The benefit to humanity comes from earlier warning. If you track variability and season timing, not just averages, you can spot dangerous shifts sooner and design smarter adaptation strategies.

Research findings are available online in the journal Nature Geoscience.

The original story "Rainfall became irregular during Earth’s hottest periods, raising global warming concerns" is published in The Brighter Side of News.

Related Stories

- Resilient desert plant shows how agricultural crops could beat global warming

- Ancient fossils find Pacific Ocean balances itself during global warming

- Scientists find cheap way to fight global warming using airplanes

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.

Joshua Shavit

Writer and Editor

Joshua Shavit is a NorCal-based science and technology writer with a passion for exploring the breakthroughs shaping the future. As a co-founder of The Brighter Side of News, he focuses on positive and transformative advancements in technology, physics, engineering, robotics, and astronomy. Joshua's work highlights the innovators behind the ideas, bringing readers closer to the people driving progress.