Rare prehistoric ‘Sword Dragon’ reptile unearthed in the UK

Scientists identify Xiphodracon goldencapensis, a new ichthyosaur species that bridges a major Jurassic evolutionary gap.

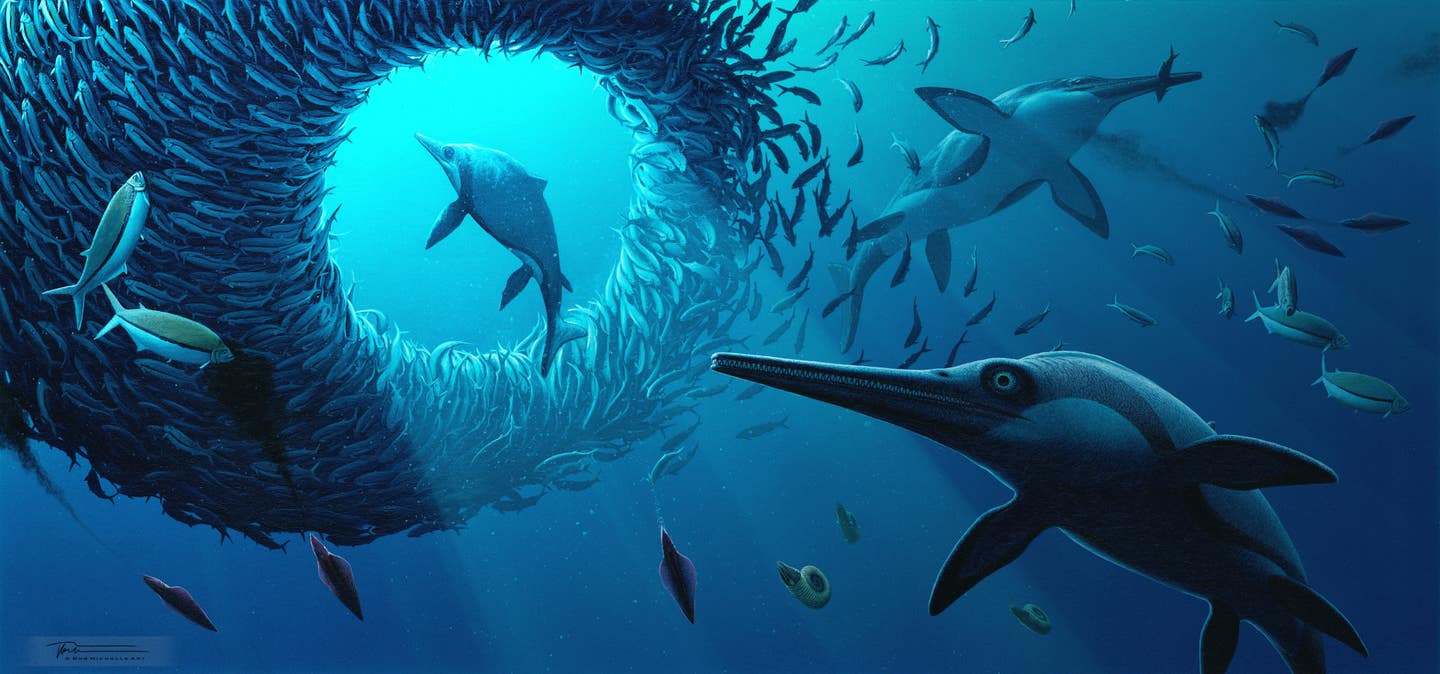

A long-snouted ichthyosaur fossil found on England’s Jurassic Coast fills a missing chapter in marine reptile evolution. (CREDIT: Bob Nicholls / University of Manchester)

A fossil found over two decades ago on England's Jurassic Coast has proved to be one of the most significant discoveries of marine reptiles in recent times. The almost complete skeleton of a long-snouted ichthyosaur—now classified as Xiphodracon goldencapensis, or the "Sword Dragon of Dorset"—is enabling scientists to piece together an incomplete chapter of evolution during the Early Jurassic era, around 193 to 184 million years ago.

Uncovering a Sea Dragon

The fossil was initially found in 2001 at Golden Cap, a cliff along the southwest England coast. It was discovered by local collector Chris Moore prior to its relocation to the Royal Ontario Museum in Canada. It stayed quite intact there until scientists at the University of Manchester and other institutions took a second look.

When Dr. Dean Lomax of the University of Manchester first looked at the fossil in 2016, he immediately knew that it was unusual. "I knew it was abnormal at the time but did not anticipate that it would turn out so significant to filling a gap in what we know," Lomax explained. The team's study determined that it represented a new species.

Measuring approximately three meters in length, Xiphodracon was roughly the size of a modern dolphin. It had a massive eye socket and a wide, sword-like snout edged with rows of sharp teeth—perfect attributes for snatching fish and squid in the oceans of the ancient past. Its name comes from the Greek xiphos (sword) and dracon (dragon), a nod to the "sea dragon" label that ichthyosaurs have had for more than 200 years.

A Window on a Lost World

The Early Jurassic Pliensbachian stage has been the frustrating, long-standing gap in the fossil record. There have been thousands of ichthyosaur skeletons found before and after that time, but fossils from within the Pliensbachian are scarce. That missing information has had scientists curious about how sea reptiles had evolved during the span of that epoch of prehistory.

Before the discovery of Xiphodracon, researchers already noted that the ichthyosaur genus before and after the Pliensbachian were quite different from one another even though they occupied the same ecological niches. The new fossil shows that this "turnover" in evolution occurred earlier than previously believed. Its presence shows that it has stronger affinities to taxa of the later Toarcian age, which extends the period of when newer ichthyosaur clades came to replace older ones.

This is a key time for the ichthyosaurs because a few of the families did become extinct and some new ones cropped up," Lomax said. "But Xiphodracon is one that you can say is missing from the ichthyosaur jigsaw."

Anatomy, Injuries, and Signs of a Struggle

The fossil has been remarkably well-preserved. There is nearly all of the skeleton intact and three-dimensional—not flat like most fossils. The only exception is the single hind flipper and the tail tip. The researchers also discovered signs of trauma: tooth marks on the skull show that the reptile had been bitten by a larger predator, possibly another ichthyosaur. A few of the teeth and bones are deformed and can show signs of disease or stress, and give an insight into dangers of Jurassic oceans.

One especially strange feature caught scientists' attention: a prong-like bony bump near the nostril, part of a bone called the lacrimal. No other ichthyosaur is known to possess such a thing. Its purpose is still a mystery—it may have affected breathing, streamlined swimming, or enhanced sensory perception—but it's a suggestion that these animals were more anatomically diverse than had been thought.

Filling Evolution's Gaps

Paleontologists call periods like these "faunal turnover," where old species die out and are replaced by new species. Ichthyosaurs experienced just such a shift during the Pliensbachian. But researchers couldn't say until now when the turnover began. Xiphodracon completes the missing record that the evolutionary change was gradual rather than abrupt.

As co-author Professor Judy Massare of the State University of New York puts it, "Thousands of complete or nearly complete ichthyosaur skeletons are known before and after the Pliensbachian. Something catastrophic happened to species diversity sometime during the Pliensbachian, that's certain. Xiphodracon allows us to pinpoint when the change took place, but we still don't know why."

That "why" is among the greatest questions of paleontology. Climatic change, sea temperature change, or competition for food might have been causes. Each new fossil discovery from this time has the potential to reveal even more pieces of the puzzle.

The Long Journey to Discovery

Xiphodracon sat unrecognized in Royal Ontario Museum collections for decades. Its importance wasn't obvious until new analytical techniques and comparisons made its uniqueness unavoidable. The tale underscores the utility of museum archives, where even fossils stored for centuries can contain solutions to scientific puzzles.

The fossil will go on display at some point at the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto, where the public will be able to see what paleontologists are calling the most complete Pliensbachian marine reptile skeleton on Earth. It's evidence that the Jurassic Coast—already a global hotspot for fossils—still has many secrets left to give.

Questions Still Unanswered

Although Xiphodracon has provided some information about some of the evolution of ichthyosaurs, there is still a great deal that is not known. Why, for instance, did it possess its unique pronglike snout bone? How common was the species—was it found only in the waters of the seas surrounding England, or was its range more extensive? And why did the general change in ichthyosaur species in the Pliensbachian take place?

The scientists hope that continued field trips and repeated studies of the fossilized creatures already in museums will provide some of those answers. Each new find can continue to refine the timeline for how these rapid, dolphin-like reptiles developed and flourished in prehistoric oceans.

Practical Implications of the Research

This discovery not only rewriting the ichthyosaur family tree—rewrites the image of how evolution unfolds in the sea. By putting Xiphodracon goldencapensis on the map as an early representative of subsequent ichthyosaur groups, researchers can now more accurately reconstruct evolutionary leaps.

The research also highlights the importance of keeping museum collections and examining specimens, where overlooked specimens are still able to overturn our understanding.

More broadly, it shows that radical evolutionary transformations can occur slowly and unnoticed, rather than suddenly—a lesson applicable to the study of diversity and extinction in the rapidly changing marine ecosystems of the present day.

Research findings are available online in the journal Papers in Palaeontology.

Related Stories

- Rare Antarctic fossil discovery has rocked scientific understanding of ancient marine reptiles

- Newly discovered Plesiosaur species rewrites Jurassic history

- 11-year-old girl finds fossil of largest marine reptile ever to swim Earth’s oceans

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.

Joseph Shavit

Science News Writer, Editor-At-Large and Publisher

Joseph Shavit, based in Los Angeles, is a seasoned science journalist, editor and co-founder of The Brighter Side of News, where he transforms complex discoveries into clear, engaging stories for general readers. With experience at major media groups like Times Mirror and Tribune, he writes with both authority and curiosity. His work spans astronomy, physics, quantum mechanics, climate change, artificial intelligence, health, and medicine. Known for linking breakthroughs to real-world markets, he highlights how research transitions into products and industries that shape daily life.