Record-breaking neutrino points to exploding primordial black hole

A 2023 neutrino with record energy left scientists scrambling. UMass Amherst physicists say a dying primordial black hole may explain it.

Edited By: Joshua Shavit

Edited By: Joshua Shavit

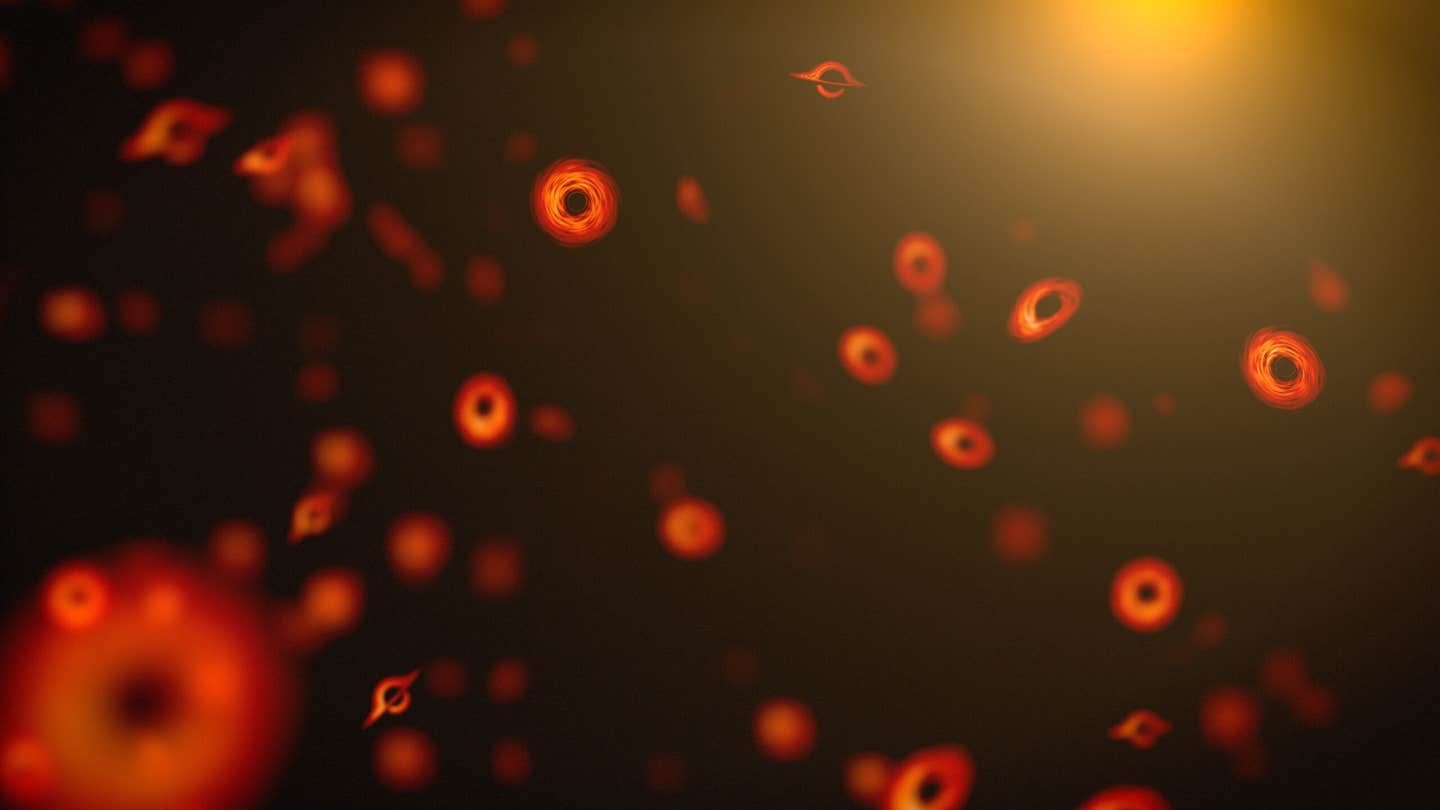

A 220 PeV neutrino may have come from an exploding primordial black hole with a hidden “dark charge,” researchers report. (CREDIT: Wikimedia / CC BY-SA 4.0)

A neutrino slammed into Earth in 2023 with so much energy that it looked almost unreal. The particle carried about 220 peta–electron volts, or PeV, making it the most energetic neutrino ever reported. That is roughly 100,000 times more energy than the highest-energy particle produced by the Large Hadron Collider.

Now physicists at University of Massachusetts Amherst say the event may fit a bold explanation. In a study published in Physical Review Letters, they argue the neutrino could have come from a tiny, ancient black hole that reached the end of its life and detonated. The team includes Andrea Thamm, Joaquim Iguaz Juan and Michael Baker.

The detection came from the KM3NeT Collaboration, a neutrino experiment in the Mediterranean Sea. It recorded the event called KM3-230213A. The puzzle deepened because IceCube Neutrino Observatory, a larger and longer-running detector, did not see anything like it.

A record neutrino and an awkward mismatch

When two major detectors tell different stories, you have to ask why. IceCube has observed high-energy neutrinos for years. It has measured events in the PeV range. Yet KM3NeT spotted a far rarer, far more energetic event first.

If the 220 PeV neutrino came from a steady, all-sky background, the two experiments appear to be in about 3.5-sigma tension. If it came from a brief point source, that tension drops to about 2 sigma. Either way, the mismatch pressures scientists to explain what kind of source could produce such energy, and why one detector would catch it before the other.

That is where the UMass Amherst idea enters. The researchers focus on primordial black holes, hypothetical black holes formed soon after the Big Bang. Unlike the black holes made by collapsing stars, primordial black holes could be tiny. Some could be light enough to die today.

A black hole that can blow up

Primordial black holes, or PBHs, remain unconfirmed. But they carry a powerful promise. In 1970, Stephen Hawking showed that black holes should emit radiation because of quantum effects near the event horizon. Over long times, that radiation robs a black hole of mass.

“The lighter a black hole is, the hotter it should be and the more particles it will emit,” says Thamm. “As PBHs evaporate, they become ever lighter, and so hotter, emitting even more radiation in a runaway process until explosion. It’s that Hawking radiation that our telescopes can detect.”

If you observe a final PBH blast, you do not just spot a fireworks show. You also get a particle inventory. The outburst would include familiar particles, like electrons and quarks. It could also include particles nobody has seen, including candidates for dark matter.

The UMass Amherst group has argued before that PBH explosions could occur surprisingly often, perhaps on the scale of once a decade. The 2023 neutrino, they say, looks like the kind of clue you might expect if one exploded close enough.

The “dark charge” twist

A straightforward PBH explosion model runs into a problem. Past work on uncharged PBHs suggests that matching the KM3NeT event would require a huge burst rate. That rate would also imply IceCube should see many more events. On top of that, large PBH explosion rates can clash with limits from the extragalactic gamma-ray background. Those limits generally allow only a small local burst rate, around 0.01 to 0.1 per cubic parsec per year.

So the researchers added complexity. “We think that PBHs with a ‘dark charge’; what we call quasi-extremal PBHs; are the missing link,” says Iguaz Juan. In their model, the black hole carries charge, not in ordinary electromagnetism, but in a hidden force. The team assumes a dark U(1) symmetry with a massless “dark photon” and a heavy “dark electron.” They also assume the dark photon barely mixes with normal light.

“There are other, simpler models of PBHs out there,” says Baker; “our dark-charge model is more complex, which means it may provide a more accurate model of reality. What’s so cool is to see that our model can explain this otherwise unexplainable phenomenon.”

A PBH with a stable dark charge behaves differently as it shrinks. As the black hole loses mass, its effective charge parameter rises toward an extreme state called “quasi-extremal.” In that state, Hawking radiation becomes strongly suppressed. The black hole can linger in a long-lived, metastable phase.

“A PBH with a dark charge,” adds Thamm, “has unique properties and behaves in ways that are different from other, simpler PBH models. We have shown that this can provide an explanation of all of the seemingly inconsistent experimental data.”

Eventually, the researchers say, the PBH discharges through a dark-sector version of the Schwinger effect. After that discharge, the PBH can explode like an uncharged black hole.

Why KM3NeT could win the race

To check whether their idea could work, the researchers first ran detailed models of how tiny primordial black holes would change as they aged. They tracked how the black holes lose mass and how their hidden, or “dark,” charge behaves over time. From there, they estimated how many neutrinos would be released during the black hole’s final moments. Some neutrinos would come straight from the explosion itself, while others would form later, when emitted particles break apart and decay.

What matters most is not just that these black holes can produce neutrinos, but how the energy of those neutrinos is spread out. In this model, neutrinos with lower extreme energies, around 1 PeV, are strongly reduced, while much higher-energy neutrinos, closer to 100 PeV, are less affected. That detail turns out to be crucial. IceCube mostly detects neutrinos near the lower end of that range, while the KM3NeT event was far more energetic. A skewed energy pattern like this could help explain why the two detectors saw such different things.

To make fair comparisons, the researchers set clear energy cutoffs for each experiment. For IceCube, they focused on neutrinos above 1 PeV, matching what the detector usually sees. For KM3NeT, they used a much higher cutoff, 35 PeV, based on the energy range tied to the 2023 detection. They also assumed the black holes being modeled were old enough to be exploding today, choosing starting masses that would let them survive for the entire age of the universe.

The team then scaled up from a single black hole to a whole population. They assumed these primordial black holes would be spread through the Milky Way in the same way as dark matter. Using that setup, they calculated how often black hole explosions would need to happen near Earth to match what each detector observed.

In simpler models without a dark charge, the numbers do not agree at all. KM3NeT would require explosion rates thousands of times higher than what IceCube’s data suggests. But when the researchers included dark-charged black holes, that gap narrowed. Under certain conditions, both experiments could be explained by similar explosion rates, without breaking existing limits from other cosmic measurements.

The same model also touches on a much bigger question. Astronomers know that dark matter exists because of how galaxies move and how the early universe looks, but they do not know what it is made of. The researchers argue that if these dark-charged primordial black holes are real, there could be enough of them to account for some, or even all, of the missing matter in the universe.

Practical Implications of the Research

If this model holds up, you gain a new way to test some of physics’ hardest ideas with real sky data. A confirmed PBH explosion would strengthen the case for Hawking radiation. It would also turn neutrino telescopes into tools for particle discovery, not just cosmic astronomy.

The work also offers a fresh angle on dark matter. If some dark matter consists of primordial black holes with hidden charge, future surveys could look for signatures that match this specific neutrino pattern, including fewer PeV events than expected and occasional far higher-energy bursts.

Finally, the study gives experiments a concrete target. By comparing KM3NeT, IceCube, and gamma-ray background limits together, you can narrow the allowed range of dark-sector properties. That kind of cross-check can guide detector upgrades and help decide what signals deserve the most follow-up.

Research findings are available online in the journal Physical Review Letters.

Related Stories

- Computer models reveal how early black holes grew so quickly after the Big Bang

- JWST discovers a massive primordial black hole that may have formed before stars

- Astronomers watch a supermassive black hole X-ray flare ignite an ultra-fast galactic wind

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.

Joseph Shavit

Writer, Editor-At-Large and Publisher

Joseph Shavit, based in Los Angeles, is a seasoned science journalist, editor and co-founder of The Brighter Side of News, where he transforms complex discoveries into clear, engaging stories for general readers. With vast experience at major media groups like Times Mirror and Tribune, he writes with both authority and curiosity. His writing focuses on space science, planetary science, quantum mechanics, geology. Known for linking breakthroughs to real-world markets, he highlights how research transitions into products and industries that shape daily life.