Red giant starquakes reshape what scientists think about quiet black holes

Astronomers decode starquakes in two Milky Way systems, exposing a stellar merger and the limits of black hole measurements.

Edited By: Joshua Shavit

Edited By: Joshua Shavit

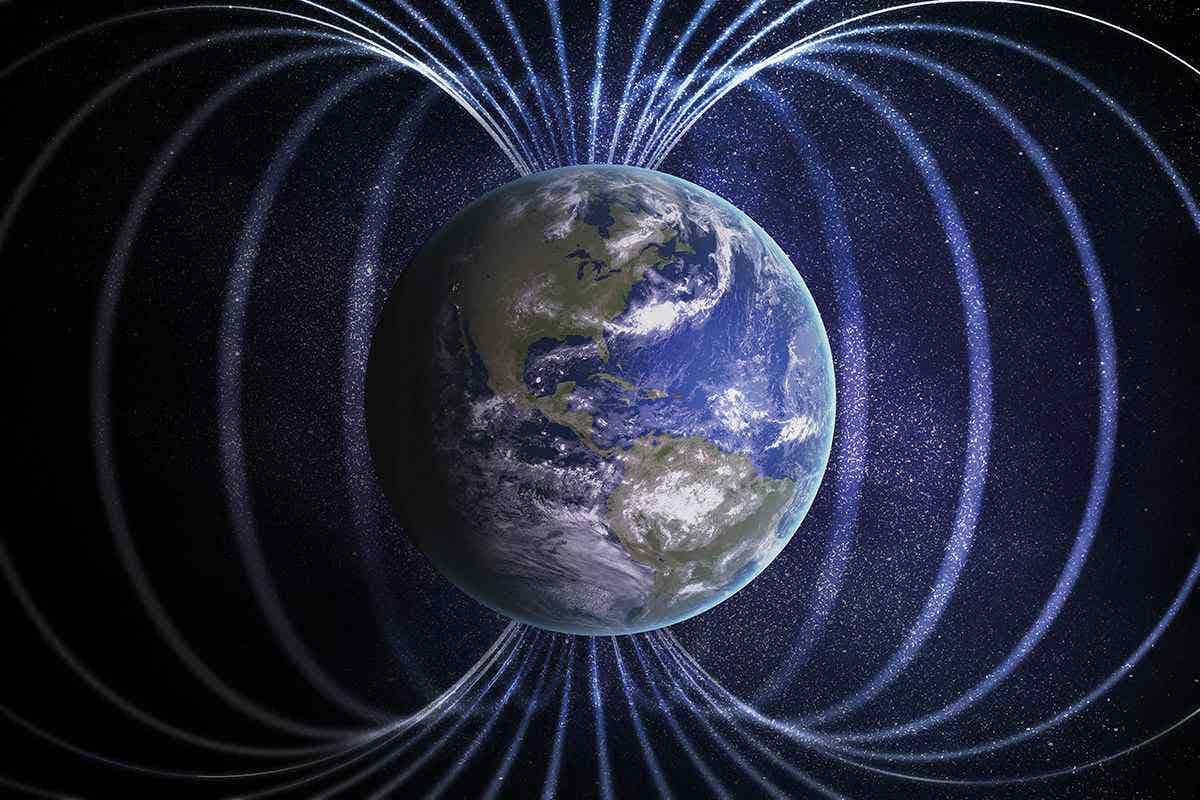

AI-generated image of red giant star orbiting a quiet black hole in the Gaia BH2 system. (CREDIT: ESO/L. Calçada/Space Engine)

You live in a galaxy packed with black holes that never announce themselves. They do not blaze in X-rays or glow with stolen gas. They hide. Astronomers find them by watching the stars that dance around them.

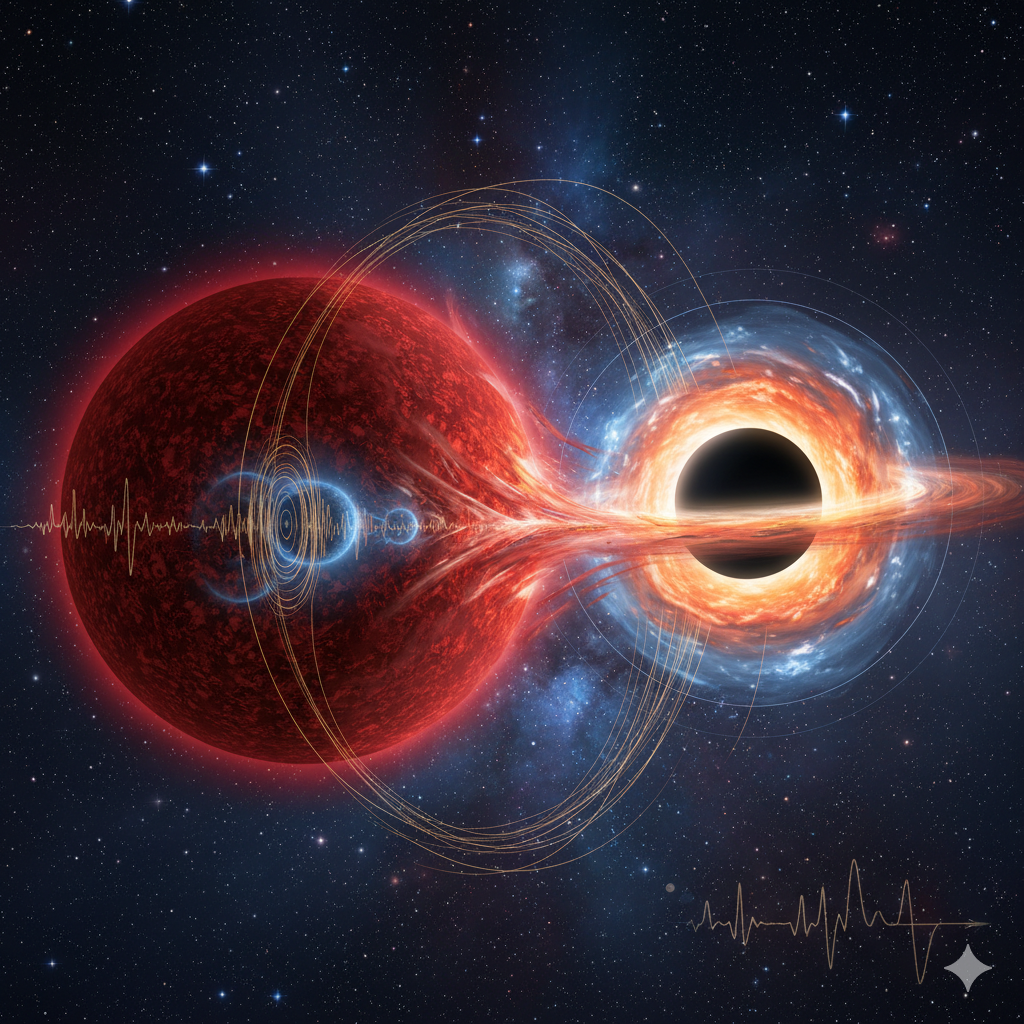

Two such systems, called Gaia BH2 and Gaia BH3, sit in your own Milky Way. Each pairs a red giant with a dormant black hole, meaning the black hole feeds on almost nothing and gives off almost no light. A new investigation shows that the visible stars tell sharply different stories about their pasts, and those stories reshape how you think about quiet black holes.

Listening for Starquakes

Red giants flicker. Their surfaces rise and fall in tiny rhythms that change the light you see. Space telescopes such as NASA’s Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite capture those faint beats. Astronomers treat them like heart sounds. From them, they infer a star’s size, mass, and age.

That method has a name, asteroseismology. It works because the spacing and strength of the flickers depend on a star’s internal structure. If you misjudge the star, you misjudge the black hole orbiting it. Precision matters.

A Star That Sings

In the Gaia BH2 system, the red giant sings loudly enough to hear. Scientists pulled years of TESS data and stitched the light into a clean curve. A clear pattern appeared. The star’s interior pressure waves set the rhythm.

Those pulses revealed a mass close to earlier estimates and a radius slightly larger, still within error. The shock came with the age. The star looked young, under about eight billion years, but its chemistry suggested it should be old. It is rich in alpha elements, a signature common in ancient stars nearby.

That mix of youth and old chemistry makes no sense if the star lived alone. To match the numbers with standard models, the star would need extra mass added long after birth.

Spinning Too Fast

Ground surveys then revealed slow, repeating streaks in brightness. One cycle stood out at about 398 days. The team reads that as the star’s rotation, caused by surface features moving in and out of view.

A lone red giant should spin far more slowly by now. But this one sits in an odd, stretched orbit with its black hole. Theory predicts a special spin rate in such orbits, where tidal forces tug the star toward a steady pace. That predicted rate nearly matches the observed one.

“It can’t be explained by the star’s birth spin alone,” said Joel Ong, a NASA Hubble Fellow at the University of Hawaiʻi Institute for Astronomy. “The star must have been spun up through tidal interactions with its companion, which further supports the idea that this system has a complex history.”

Evidence of a Past Collision

The simplest story fits hard evidence. The star likely stole mass from a partner, or merged with one, before it met the black hole it orbits today. Such events can make a star look young again and speed its spin.

The research team used multiple sets of models to test that idea. All paths pointed the same way. This red giant is not what it pretends to be. It is a survivor of a crash.

“Just like seismologists use earthquakes to study Earth’s interior, we can use stellar oscillations to understand what’s happening inside distant stars,” said Daniel Hey, lead author and research scientist at the Institute for Astronomy. “These vibrations told us something unexpected about this star’s history.”

The Star That Refused to Ring

Gaia BH3 tells the opposite tale. Its black hole is enormous, about 33 times the Sun’s mass. Its red giant is ancient and poor in heavy elements, a classic fossil from the early galaxy.

Predictions were clear. The star should show strong flickers. It did not.

TESS watched it closely. The light stayed flat. The expected signals never rose above the noise.

Researchers tried everything sensible. They built careful models across a range of masses and compositions. They relaxed assumptions about the star’s age. They examined how dust might affect its measured brightness. Still no pulses.

Two explanations remain. The star’s basic numbers may be less precise than believed, perhaps skewed by dust along the line of sight. Or the simple formulas astronomers use do not hold for such metal-poor stars. Too few of these relics have been measured to trust rules built for younger suns.

What This Changes

The missing beats do not change the black hole’s mass in Gaia BH3. That figure stands firm. But the silence warns you about overconfidence in easy shortcuts. For ancient stars, the old recipes can fail.

For Gaia BH2, the music does more than refine numbers. It exposes a violent history that likely shaped the system you see today. Quiet black holes do not always grow up in quiet homes.

More observations are coming. Future TESS passes may capture deeper signals from Gaia BH2 that probe the star’s core. That could confirm the merger story without relying on external clues.

Practical Implications of the Research

These findings sharpen how black hole masses are measured across the Milky Way. Better star measurements mean better black hole counts. The work also flags where standard tools can mislead, especially for very old stars. That protects future surveys from quiet errors that spread through catalogs.

In time, improved methods will map hidden black holes with higher confidence and reveal how often stars collide on cosmic scales.

Research findings are available online in The Astronomical Journal.

Related Stories

- Unparalleled bounty of oscillating red giant stars detected

- Black hole stars: Giant stars may hide black holes at their core

- Red dwarf stars are unlikely to host planets with advanced life and civilizations

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.

Joseph Shavit

Writer, Editor-At-Large and Publisher

Joseph Shavit, based in Los Angeles, is a seasoned science journalist, editor and co-founder of The Brighter Side of News, where he transforms complex discoveries into clear, engaging stories for general readers. With vast experience at major media groups like Times Mirror and Tribune, he writes with both authority and curiosity. His writing focuses on space science, planetary science, quantum mechanics, geology. Known for linking breakthroughs to real-world markets, he highlights how research transitions into products and industries that shape daily life.