Researchers create new molecule to insert DNA into cells

A thymine-tipped PEG carrier delivered plasmid DNA into mouse muscle, with one formula reaching a 14-fold expression increase.

Edited By: Joseph Shavit

Edited By: Joseph Shavit

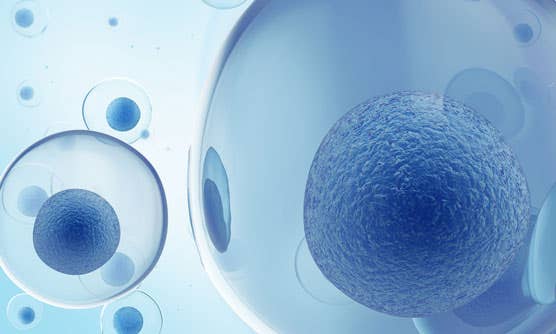

A Tokyo team built a neutral PEG-DNA complex that boosted gene expression in mouse muscle, avoiding cation-linked inflammation. (CREDIT: Wikimedia / CC BY-SA 4.0)

Getting DNA into a living cell sounds simple, until you remember the cell’s outer membrane acts like a guarded wall. DNA strands carry a negative charge, and they do not cross that wall easily. So for years, many genetic therapies and DNA-based vaccines have depended on delivery helpers that are strongly positively charged, because opposite charges stick. That trick works, but it can come with baggage: irritation, inflammation, and messy clumping with other molecules in the body.

A team led by Professor Shoichiro Asayama at Tokyo Metropolitan University set out to dodge that tradeoff. Their approach uses an uncharged polymer, paired with a small DNA “handle,” to escort plasmid DNA into cells. In mouse experiments, their best formulation produced luciferase gene expression that tended to be about 14 times higher than annealed DNA delivered without a carrier, with results reported as p < 0.1 in groups of four mice.

The goal is not a new gene-editing tool. It is a new way to carry DNA safely, particularly into skeletal muscle, where the surrounding environment can make charged delivery systems behave badly.

Why muscle is a tough neighborhood for DNA delivery

Plasmid DNA is a circular piece of DNA that can instruct cells to make specific proteins or RNAs. In gene therapy, that can mean producing therapeutic proteins. The source material also notes plasmids can be used to produce RNA molecules such as short interfering RNA, messenger RNA, and noncoding RNA.

The trouble starts after injection. The DNA has to survive and then get taken up by cells. One major strategy has been nonviral carriers built from biocompatible cationic polymers. These positively charged carriers bind the negatively charged plasmid through electrostatic attraction, forming what researchers often call a polyion complex. This can stabilize DNA in the body and improve uptake.

But in muscle, that positive charge can backfire. Muscle fibers sit within a strongly negatively charged extracellular matrix. The source describes two linked problems: cationic complexes can bind nonspecifically to anionic molecules in the body, and in muscle tissue that can reduce transfection efficiency and trigger inflammation at the injection site.

Asayama’s work has explored ways to reduce those strong charge interactions before. The new study pushes that idea further by trying to build a plasmid DNA complex that relies only on hydrogen bonding, with no cations at all.

A single DNA base, used like Velcro

The carrier at the center of the study is poly(ethylene glycol), better known as PEG. PEG is widely used and often described as inert in the body. The team chemically modified PEG so that a single thymine base sat at one end of each PEG strand.

Thymine is one of the four nucleobases in DNA. In natural double-stranded DNA, thymine pairs with adenine through Watson–Crick hydrogen bonds. The researchers wanted to exploit that pairing to attach PEG to plasmid DNA without relying on charge.

There was a catch. In intact double-stranded plasmid DNA, the adenine bases that thymine would normally pair with are already bonded to thymine bases on the opposite strand. So the researchers used a thermal treatment called annealing to partially dissociate the plasmid’s duplex structure and expose bases for binding.

They did not simply heat the plasmid and hope for the best. They measured the plasmid’s melting behavior, seeing signs of structural change starting around 65 °C and a major shift from around 80 to 90 °C, with complete dissociation suggested around 90 °C. Based on gel electrophoresis results, they selected annealing at 85 °C for 5 minutes as a practical middle ground, aiming to increase base accessibility while still maintaining the plasmid’s structure.

Salt and DNA concentration also mattered. The team reported the strongest signal for their annealing-derived DNA band at 0.2 mM sodium ions and a plasmid DNA concentration of 0.06 mg/mL. Higher sodium levels appeared to suppress dissociation by reducing electrostatic repulsion within the DNA duplex.

The complex that forms, and why the “right” ratio matters

Once the plasmid was annealed under those conditions, the modified PEG, called Thy-PEG, could bind by hydrogen bonding, forming what the researchers call a single-nucleobase-terminal complex, or SNTC.

Because Thy-PEG is uncharged, standard gel electrophoresis did not show clear band shifts. To confirm complex formation, the researchers added DNase, an enzyme that digests DNA. In the presence of DNase, plasmid bands were retained at certain carrier-to-DNA ratios, suggesting the DNA had gained protection through complex formation. The best retention appeared around a hydrogen-bonding-terminal to base ratio (H/B) of roughly 0.5, depending on the PEG length.

Too much carrier could hurt. The researchers suggest excess Thy-PEG might compete for hydrogen bonding and reduce effective binding.

They also checked cytotoxicity in mouse myoblast C2C12 cells. A positively charged polymer control, branched poly(ethylenimine), reduced cell viability when compared on the basis of equivalent molar concentrations of charged groups, while the Thy-PEG materials did not show the same cytotoxic effect. The authors attribute this to Thy-PEG being nonionic.

Particle size measurements showed the Thy-PEG/plasmid complexes had a most frequent size of about 100 nanometers under the tested conditions, with negative zeta potentials that did not strongly correlate with PEG length or H/B ratio.

A mouse test points to one standout formulation

The in vivo test came next. Male ICR mice, 5 weeks old, received tibialis muscle injections of complexes made with different PEG chain lengths and different H/B ratios. The plasmid encoded a firefly luciferase gene under a cytomegalovirus promoter, and expression was measured one week later as luciferase activity normalized per milligram of protein.

Not every version worked well. The standout was Thy-PEG with a PEG molecular weight of 5k. At an H/B ratio of 0.5, luciferase expression tended to be about 14-fold higher than expression from annealed plasmid DNA alone, with p < 0.1 and n = 4. A similar result, about 12-fold higher, appeared at an H/B ratio of 1.0. Thy-PEG10k at an H/B ratio of 0.25 produced about a 4-fold increase compared with annealed plasmid DNA, while other combinations did not show meaningful improvement in this dataset.

The team points out that particle size and zeta potential looked broadly similar across complexes. So they argue the difference may come from more subtle structural features, describing the Thy-PEG5k complex as having an “optimal uncondensed flexible structure” with PEG chains that may help deliver plasmid DNA into parts of skeletal muscle that naked plasmid DNA cannot easily reach.

To support the importance of base-specific binding, the researchers also tested an amide end-modified PEG that can form hydrogen bonds more broadly with DNA bases. In a separate comparison described as a negative control, the Am-PEG5k/plasmid complex at an H/B ratio of 1.0 produced about a 5-fold increase over annealed plasmid DNA, lower than the Thy-PEG5k results.

Research findings are available online in the journal ACS Applied Bio Materials.

The original story "Researchers create new molecule to insert DNA into cells" is published in The Brighter Side of News.

Related Stories

- New sensor captures DNA breaks, repair inside living cells in real time

- New DNA tool detects 'zombie cells' linked to Alzheimer’s and arthritis

- New experimental molecules encourage cells to work harder and burn more calories

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.

Hannah Shavit-Weiner

Medical & Health Writer

Hannah Shavit-Weiner is a Los Angeles–based medical and health journalist for The Brighter Side of News, an online publication focused on uplifting, transformative stories from around the globe. Passionate about spotlighting groundbreaking discoveries and innovations, Hannah covers a broad spectrum of topics—from medical breakthroughs and health information to animal science. With a talent for making complex science clear and compelling, she connects readers to the advancements shaping a brighter, more hopeful future.