Russia patents a modular spacecraft designed to create artificial gravity

Russia has patented a rotating spacecraft design that could create artificial gravity for long-duration space missions.

Edited By: Joseph Shavit

Edited By: Joseph Shavit

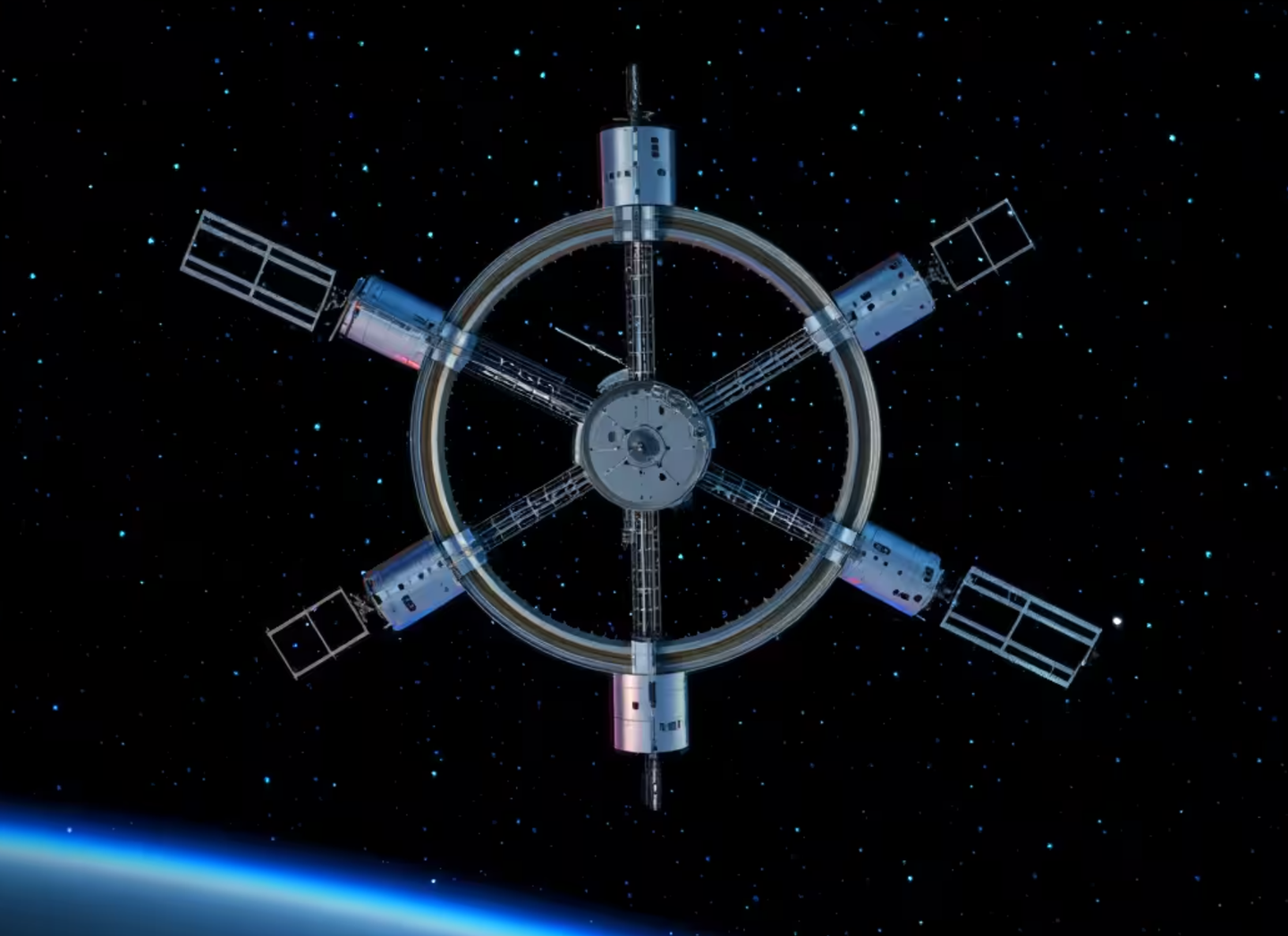

Russia’s Energia Space Rocket Corporation has patented a modular spacecraft that uses rotation to generate artificial gravity, a step that could reshape long-duration human spaceflight. (CREDIT: Reve)

Human spaceflight is once again confronting a familiar problem: how to protect astronauts during long missions far beyond Earth. Engineers at Russia’s Energia Space Rocket Corporation, part of the state-run space agency Roscosmos, have proposed a new answer. According to a patent obtained by the Russian news agency TASS, the company has designed a modular spacecraft system that generates artificial gravity by rotating its living sections.

The patent describes a space system built around a central axial module with both static and rotating components. These parts connect through a hermetically sealed flexible junction. Radially attached habitable modules rotate around the core, creating a centrifugal force that mimics gravity. The design aims to produce 0.5g, about half of Earth’s gravity, a level researchers believe could significantly reduce the health risks of long-term weightlessness.

Russia has not announced funding or a timeline for building the system. Still, the patent signals renewed interest in artificial gravity as the International Space Station approaches retirement.

Why Artificial Gravity Matters for Human Health

You already know that spaceflight changes the human body. Months in microgravity weaken muscles, thin bones, and alter circulation. Astronauts exercise daily aboard the ISS, yet bone density loss and muscle shrinkage remain serious concerns.

Artificial gravity offers a potential solution. By rotating living spaces, spacecraft can generate forces that pull occupants toward the outer walls. Over time, this load could help preserve muscle strength and bone health. Researchers have studied partial gravity for decades, and many believe even half of Earth’s gravity could provide major benefits.

Energia’s concept joins a long line of attempts to solve this problem. NASA explored rotating designs such as the Nautilus-X concept, while private companies like Vast have announced plans for spinning space stations. Each effort, however, has faced technical and safety challenges.

Lessons From Earlier Concepts

Earlier artificial-gravity designs revealed critical weaknesses. Nautilus-X, for example, relied on a rotating torus connected to a central corridor by a single passage. If that connection failed, crew members could become trapped. The fixed torus also complicated launch and assembly.

More recent commercial concepts require visiting spacecraft to match the station’s rotation before docking. That step increases the risk of collision and demands precise coordination. Older designs using counterweights and multiple sealed rotary joints raised similar safety concerns. Failures in those systems could block crew movement or isolate entire sections.

Energia’s engineers used these lessons to rethink how rotating habitats connect to a spacecraft’s core.

Inside the New Rotating Architecture

At the heart of the patented system is an axial module made of two shells. One shell remains static. The other rotates and combines spherical and cylindrical surfaces. A sealed movable joint connects the two.

Crucially, all rotating and sealing components sit on one side of the rotating shell. Bearings, gaskets, and the gear system that drives rotation are grouped together. This layout reduces the chance that a single failure could block crew passage or compromise safety.

An electric motor drives a gear ring attached to the rotating shell. By controlling rotation speed, the system generates the desired artificial gravity. The spherical end of the rotating shell includes both axial and radial docking ports. These ports allow multiple habitable modules to connect while maintaining structural balance.

Living and Moving Inside the Station

Each habitable module includes a transfer compartment and a living compartment. The transfer section functions as a telescoping tunnel. It contains both fixed and extendable segments, along with power systems and structural supports. Crew members can move through the tunnel using electromechanical aids or ladder-based access, whether the station is rotating or not.

The living compartment attaches to a rigid base with a docking port. When deployed and pressurized, it expands into a larger space reinforced from within. Crews can configure these modules for sleeping, working, exercise, or medical care. Hatches separate all sections, allowing isolation during emergencies or maintenance.

Building the System in Orbit

Assembly follows a step-by-step process. First, the axial module launches into orbit and moves to an assembly location. Transport spacecraft then dock with the axial port. Habitable modules launch separately and dock in sequence.

Each module initially connects to the axial port, then automatically relocates to a radial port using a redocking system. Once all modules are in place, crews extend the telescoping tunnels and deploy the living shells. Seals lock the connections, and the structure is pressurized.

After assembly, electric motors gradually spin the system up to its operating speed.

How Much Gravity Can It Provide?

Medical studies guided the design target. Engineers calculated that a rotation rate of about five revolutions per minute, combined with a radius of roughly 40 meters, would generate 0.5g. That balance limits motion sickness while delivering meaningful gravitational load.

The design also preserves a non-rotating central zone. Crews can perform experiments requiring weightlessness in the static core, while living and exercising in the rotating habitats.

Practical Implications of the Research

This patented design highlights how artificial gravity could change the future of human spaceflight. If developed, such systems may allow astronauts to stay in orbit or travel through deep space for longer periods with fewer health risks. Partial gravity could reduce bone loss, muscle decline, and cardiovascular strain, easing the burden of rehabilitation after missions.

For researchers, the system offers a platform to study how the human body responds to sustained partial gravity. Those insights could shape future spacecraft, lunar habitats, and missions to Mars. For humanity, artificial gravity may be a key step toward safer, longer, and more sustainable exploration beyond Earth.

Related Stories

- Travelers could embark on celestial vacations to luxury space hotels by 2030

- A space elevator to the Moon is now within reach thanks to modern technology

- Beam Me Up Scotty: NASA 'Holoported' a doctor onto the International Space Station

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.

Joshua Shavit

Writer and Editor

Joshua Shavit is a NorCal-based science and technology writer with a passion for exploring the breakthroughs shaping the future. As a co-founder of The Brighter Side of News, he focuses on positive and transformative advancements in technology, physics, engineering, robotics, and astronomy. Joshua's work highlights the innovators behind the ideas, bringing readers closer to the people driving progress.