Scientists build an electrostatic ‘tractor beam’ to move space junk safely

Scientists test electrostatic tractor beams to move space debris, while similar physics may help deflect small asteroids.

Edited By: Joseph Shavit

Edited By: Joseph Shavit

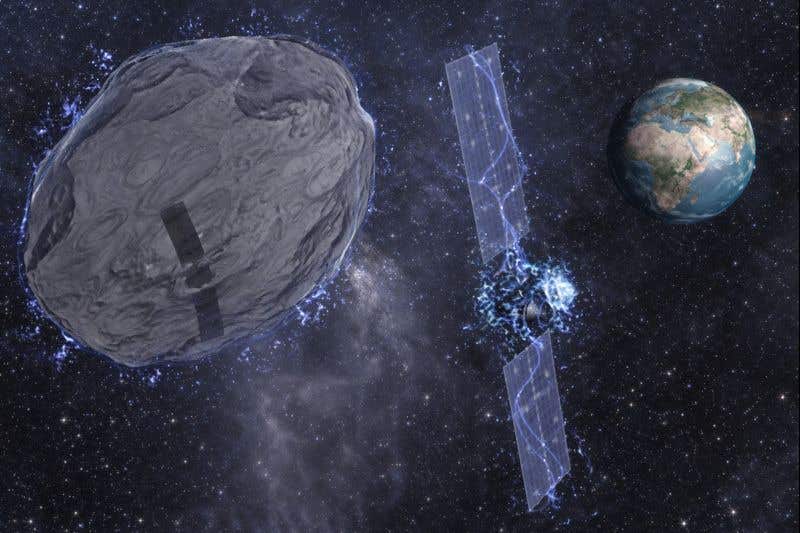

Artistic impression of the Electrostatic Tractor during an Earth encounter. (CREDIT: Fabio Annecchini & Dario Izzo)

A dead satellite can become a high-speed hazard in an orbit that is already packed with working spacecraft. That risk is why engineers at the University of Colorado Boulder are building what sounds like science fiction; a “tractor beam” that can pull space junk without ever touching it. Their work also echoes a parallel idea in planetary defense: nudging an asteroid off course using forces you can control, even when gravity alone is too weak.

At CU Boulder, Professor Hanspeter Schaub and his team are testing electrostatic “tugs” in a custom vacuum facility on the university’s East Campus. Doctoral students Julian Hammerl and Kaylee Champion are part of the group tackling the hard part: making electric forces behave predictably in the messy plasma environment around Earth and beyond.

"The problem with space debris is that once you have a collision, you're creating even more space debris," said Julian Hammerl, a doctoral student in aerospace engineering sciences at CU Boulder. "You have an increased likelihood of causing another collision, which will create even more debris. There's a cascade effect."

A tractor beam built for crowded orbits

Space debris became a public warning sign on Feb. 10, 2009, when a defunct Russian satellite struck Iridium 33 over Siberia, breaking both into thousands of pieces. NASA estimates that about 23,000 debris objects the size of a softball or larger now orbit Earth. Each one raises the odds of another chain reaction, where one crash creates fragments that cause more crashes.

Schaub’s group wants to prevent that cascade by moving old spacecraft away from valuable orbital “parking spots.” The idea relies on electrostatics, the same basic physics behind static cling. One craft charges another, and the two feel an attractive or repulsive force.

"We're creating an attractive or repulsive electrostatic force," said Schaub, chair of the Ann and H.J. Smead Department of Aerospace Engineering Sciences. "It's similar to the tractor beam you see in Star Trek, although not nearly as powerful."

That tug could matter most in geosynchronous orbit, the region roughly 22,000 miles above Earth where many large military and communications satellites operate. Schaub calls it an “expensive patch of real estate,” and he has a shorthand comparison.

"GEO is like the Bel Air of space," Schaub said.

The lab that mimics “space in a can”

To test the concept, the team built a chamber called the Electrostatic Charging Laboratory for Interactions between Plasma and Spacecraft, or ECLIPS. It can be pumped down to near vacuum over about a day, creating a small, controlled pocket that behaves like space. Inside, the researchers can introduce plasma, then place metal shapes that stand in for debris.

Those details matter because orbit is not empty. It is filled with plasma, and plasma tends to shield electric fields. What looks simple on a whiteboard becomes tricky when the field you create gets distorted, or when a charged object draws in opposite charges from its surroundings.

"Touching things in space is very dangerous. Objects are moving very fast and often unpredictably," said Kaylee Champion, a doctoral student working with Schaub. "This could open up a lot of safer avenues for servicing spacecraft."

Hammerl describes the tug as a “virtual tether.” A servicing spacecraft approaches a dead satellite from about 15 to 25 meters, then uses an electron beam to charge it. That makes the debris more negative, while making the servicer more positive, so the two attract.

"With that attractive force, you can essentially tug away the debris without ever touching it," Hammerl said. "It acts like what we call a virtual tether."

Based on ECLIPS experiments and computer modeling, the team estimates an electrostatic tug could move a multi-ton satellite about 200 miles in two to three months. The pace is slow, but orbital safety often rewards patience.

When the target spins, and space gets wilder

Real debris does not always cooperate. Decommissioned satellites can tumble, and a tumbling target complicates both charging and control. Schaub’s team has studied whether “rhythmic” pulses of electrons, rather than a steady beam, could reduce a satellite’s rotation. If it works, the same tool that charges the object could help calm it.

The group is also looking beyond Earth orbit to “cislunar” space between Earth and the moon, where conditions can change sharply. Champion notes that outside Earth’s magnetic shield, the solar wind can make the plasma environment less predictable. A spacecraft can disturb that flow and leave an ion wake behind it, which could alter how an electrostatic tug performs.

"That's what makes this technology so challenging," Champion said. "You have completely different plasma environments in low-Earth orbit, versus geosynchronous orbit versus around the moon. You have to deal with that."

To explore that problem in the lab, Champion’s team added an “ion gun” to ECLIPS to generate fast-moving argon ion currents. She links the work to future exploration goals tied to NASA’s Artemis Program.

"Once we put people back on the moon, that's a steppingstone to traveling to Mars," Champion said.

A sister problem: moving asteroids with more than gravity

A separate line of research focuses on deflecting near-Earth asteroids. Engineers have proposed many approaches, from kinetic impacts to nuclear devices, but “soft” methods aim to push an object gradually and predictably. The classic soft method is the gravity tractor, where a spacecraft hovers near an asteroid and uses mutual gravity as an invisible tow line. In an early reference case, a roughly 200-meter asteroid would need a 20-ton tractor and about 20 years of lead time.

Even with improved hovering geometries, gravity tractors face an unavoidable limit: gravity is weak, especially for small asteroids. That is why researchers have explored an “Electrostatic Tractor” concept. It keeps the hover-and-tug idea, but replaces some of gravity’s pull with a stronger, tunable force by charging the spacecraft and asteroid.

The details turn on force and timing. A small push applied early can change where an asteroid crosses Earth’s orbit later. The research warns that encounter geometry matters, and that a near head-on approach can make some “phase shift” deflection strategies less efficient than they look on paper. To compare methods, the study leans on deflection charts that scale with the maximum continuous force a system can apply.

Building that force with electrostatics depends on charging both objects, and keeping those charges stable in plasma. Spacecraft can control their “floating potential” using ion or electron emission, and some work suggests potentials around 20 kilovolts may be feasible with designs that prevent damaging discharges. Modeling in the study suggests a 500-kilogram spacecraft at 20 kilovolts could hold on the order of tens of microcoulombs of charge.

Asteroids are harder. The study simplifies an asteroid as a cohesive, conductive sphere, while acknowledging that real asteroids may not conduct well. It also flags uncertain issues like charge distribution and dust loss. The researchers focus on a practical hurdle: holding an asteroid at a target voltage costs power, because plasma currents flow to the charged surface and must be balanced.

Using a more detailed current model, the study finds it can be more power-efficient at high voltage to charge an asteroid negatively. It reports that maintaining roughly −20 kilovolts on an asteroid requires power that grows with size, reaching on the order of tens of kilowatts for a 100-meter-radius body. Smaller asteroids need far less power, which is why the concept looks most attractive for objects under about 100 meters in radius.

Practical Implications of the Research

For people on Earth, the most direct benefit is risk reduction. In orbit, electrostatic “tugs” offer a way to move derelict satellites without docking, grappling, or firing harpoons. If the approach matures, it could lower the chance of debris cascades that threaten communications, weather monitoring, navigation, and national security spacecraft. It could also make it easier to clear space for new satellites in geosynchronous orbit, where replacement capacity matters.

For planetary defense, the electrostatic tractor idea points to a more adjustable tool for small asteroids, where gravity tractors struggle. If engineers can reliably charge an asteroid and predict field behavior in plasma, future deflection missions may gain a safer, slower option that avoids violent fragmentation.

Just as important, this research pushes plasma modeling, high-voltage spacecraft design, and charging control methods that could spill into other fields, from spacecraft servicing to deep-space operations.

Research findings are available online in the journal ESA.

Related Stories

- Scientists just built an actual working tractor beam

- MIT engineers create a tractor beam to manipulate cells from a distance

- Scientists built the world's first laser-powered tractor beam

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.

Shy Cohen

Writer