Scientists develop a photonic transistor powered by a single photon

Purdue researchers show how one photon can control light using silicon avalanche detectors, opening doors for photonic computing.

Edited By: Joshua Shavit

Edited By: Joshua Shavit

Researchers at Purdue University have achieved a long-sought milestone, demonstrating what they call a “photonic transistor” that operates at single-photon intensities. (CREDIT: Purdue University)

Modern life runs on light. Fiber-optic cables move data across continents, lasers guide surgeries, and photons sit at the heart of quantum technologies. Yet one long-standing goal has remained elusive: letting light control light at the level of a single photon. Researchers have now shown that this is possible by rethinking how silicon responds when it detects light.

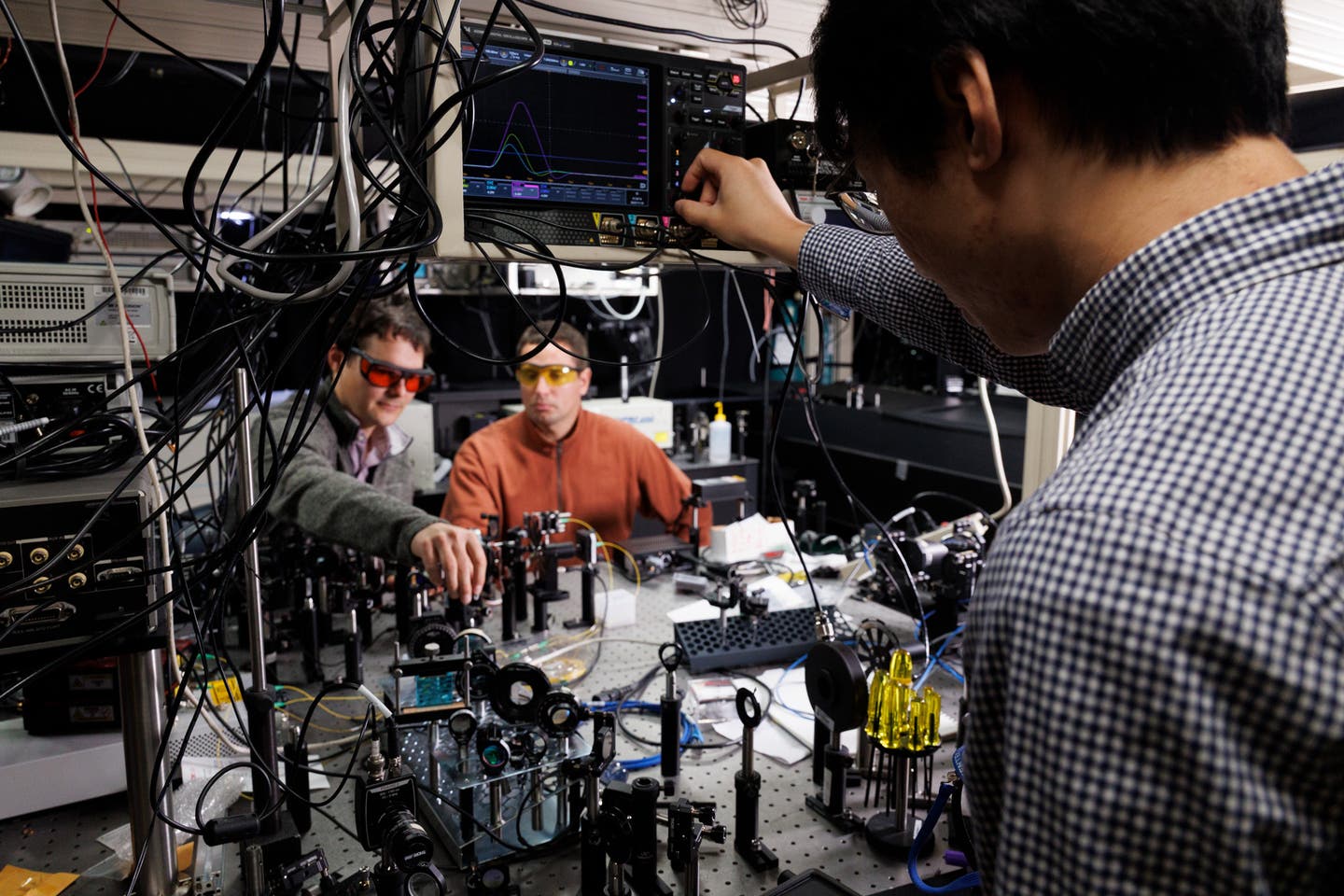

A new study from Purdue University describes an all-optical modulator that works when the control signal contains, on average, less than one photon. The work, published in Nature Nanotechnology, uses a familiar device in an unfamiliar way. Instead of treating a single-photon avalanche diode, or SPAD, purely as a detector, the researchers harness its internal avalanche process to create a dramatic optical response.

The result is a system where one visible photon can alter the behavior of a much stronger near-infrared beam at room temperature, without optical cavities or cryogenic cooling. That combination addresses a key limitation that has slowed progress in photonic computing and quantum communication.

Why controlling light with light has been so hard

All-optical modulation means using one beam of light to control another, without electronics in between. Traditional approaches rely on nonlinear optical effects, where a material’s refractive index changes slightly as light intensity increases. These effects exist in many materials, but they are weak.

Because the response is small, conventional nonlinear optics requires intense laser beams. That makes it impractical for single photons and inefficient for low-power technologies. “Usually there is optical nonlinearity, which allows two beams to interact with each other,” said Demid Sychev, a postdoctoral researcher at Purdue and first author of the paper. “But typically, this interaction works only for macroscopic beams, for classical light, because the nonlinear refractive index is very small.”

The Purdue team took a different route. Instead of trying to enhance a weak nonlinearity, they amplified the physical effect of a single absorbed photon using avalanche multiplication, a process already central to single-photon detection.

Turning a detector into a modulator

In silicon, absorbed light can change the refractive index in two main ways. It can create free charge carriers, which alter how light propagates, and it can heat the material, producing a slower optical change. On their own, these effects are tiny at the single-photon level.

A SPAD changes the picture. When biased above its breakdown voltage, a single photo-generated electron entering the device’s high-field region can trigger a chain reaction. Each energized electron knocks others loose, producing an avalanche that can multiply one electron into as many as a million in less than a nanosecond.

“This multiplication is a very powerful tool for connecting the microscopic quantum world with the macroscopic world,” Sychev said. “This principle was often used for single-photon detection, but what we did was apply this process to create a huge nonlinearity for optical beams.”

That avalanche floods the silicon with carriers and briefly heats the lattice. Both effects strongly change the refractive index and absorption. A near-infrared probe beam, with photons below silicon’s bandgap, senses these changes without creating carriers itself.

Watching fast and slow effects unfold

To track the dynamics, the researchers performed pump–probe experiments using a commercial silicon SPAD. A green control pulse at 520 nanometers triggered avalanches, while a 1,550-nanometer near-infrared pulse probed the optical response. Both pulses were shorter than 130 picoseconds, and their timing could be adjusted with 5-picosecond precision.

"The control beam was heavily attenuated so that each pulse contained, on average, only 0.1 to 1 photon. Because the pulses are coherent, their photon number follows a Poisson distribution. For a mean of one photon per pulse, the probability of having two photons is about 20 times smaller than the probability of having one photon," Sychev explained to The Brighter Side of News.

"The measurements revealed two distinct responses. A fast effect rose and fell within a few nanoseconds and was driven by the sudden burst of free carriers. A slower effect lasted for microseconds and came from local heating after the avalanche. The two contributions even affected the probe beam in opposite ways, a sign that different physical processes were at work," he continued.

Around zero delay between control and probe pulses, the modulation briefly vanished. This gap reflected the SPAD’s dead time. If one pulse triggered an avalanche, the other could not, making the probe signal look the same whether the control light was present or not.

A giant effective nonlinearity

From changes in reflected probe light, the team estimated how much the refractive index shifted. The fast response produced changes of about one part in 100,000. The slower thermal response reached nearly one part in 10,000.

When expressed as effective nonlinear coefficients, these shifts were extraordinary. The slower effect corresponded to a value more than 15 orders of magnitude larger than silicon’s conventional optical nonlinearity and 17 orders of magnitude larger than that of lithium niobate, a standard nonlinear material.

These numbers do not mean silicon has suddenly changed its fundamental properties. Instead, avalanche multiplication makes a single absorbed photon behave as if it were an intense optical signal. The physics is different, but the outcome mimics an enormous nonlinearity at vanishingly low light levels.

A photonic transistor at room temperature

The researchers also showed direct light-on-light control without lock-in detection. With a 5-megahertz pulse rate and modest probe power, they observed clear changes in near-infrared intensity as the timing shifted. The modulation reached about 0.7 decibels and was sometimes visible without averaging.

“This was a long-standing problem, and we found a potential way of solving it,” said Vladimir Shalaev, Purdue’s Bob and Anne Burnett Distinguished Professor in Electrical and Computer Engineering. He described the device as a photonic transistor, where a single photon in the control beam can switch a much stronger optical signal.

Peigang Chen, a fourth-year PhD student in Shalaev’s group, emphasized the practicality of the approach. “This is seamless and compact,” Chen said. “It is semiconductor, and it can always be fabricated on chip.”

Unlike many quantum optical systems, the device operates at room temperature and is compatible with complementary metal-oxide-semiconductor technology. The fast carrier response also suggests operation at gigahertz speeds, with the potential to go much higher.

Practical implications of the research

This work points toward optical switches that operate with minimal energy, a key step for photonic computing and low-power data processing. In quantum technologies, single-photon control could improve photon sources, enable faster quantum communication protocols, and simplify on-chip quantum circuits.

For classical systems, the impact could be broader. Optical switches that work without high power or cooling could reduce energy use in data centers and allow light-based processors to move beyond laboratory demonstrations. Because the approach relies on existing semiconductor devices, it offers a realistic path from experiment to application.

Research findings are available online in the journal Nature Nanotechnology.

Related Stories

- Silicon-photonic chip enables AI computing at light speed

- Multi-wavelength photonics breakthrough performs AI math at light speed

- Silicon qubits bring scalable quantum computing closer to reality

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.

Joseph Shavit

Writer, Editor-At-Large and Publisher

Joseph Shavit, based in Los Angeles, is a seasoned science journalist, editor and co-founder of The Brighter Side of News, where he transforms complex discoveries into clear, engaging stories for general readers. With vast experience at major media groups like Times Mirror and Tribune, he writes with both authority and curiosity. His writing focuses on space science, planetary science, quantum mechanics, geology. Known for linking breakthroughs to real-world markets, he highlights how research transitions into products and industries that shape daily life.