Scientists develop smart transparent woods that block UV and save energy

Researchers built a transparent wood composite that shifts from privacy to clarity with temperature, blocks UVA light, and insulates nearly five times better than glass.

Edited By: Joseph Shavit

Edited By: Joseph Shavit

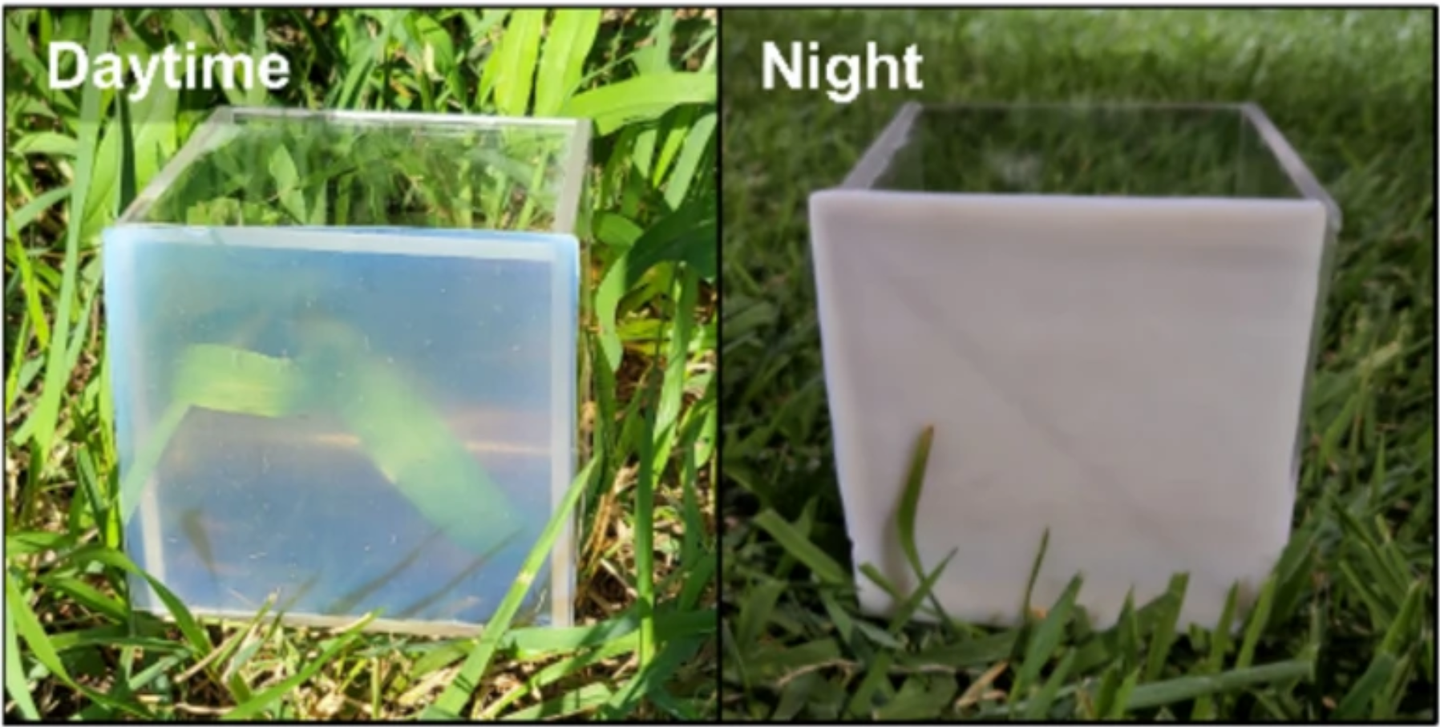

Images of PDLC/TW as one side of the showcase during the day and at night. (CREDIT: Advanced Composites and Hybrid Materials)

Researchers in the Republic of Korea are pushing smart-window design beyond glass. Professor Sung Ho Song at Kongju National University and Assistant Professor Jin Kim in the Department of Materials Science and Engineering at Hanbat National University led a project that turns chemically treated wood into a temperature-responsive window panel.

The team reports a transparent wood that can shift between hazy privacy and clear daylighting as temperatures change. It also blocks ultraviolet light and insulates far better than standard glass.

The goal targets a basic problem in building energy use. Windows admit light, but they also let heat move quickly in and out. That forces heating and cooling systems to work harder. At the same time, stronger UV exposure can harm skin and fade indoor materials.

Many existing smart windows rely on coatings and films on glass. Those layers can add cost and fragility. Even when the light-control layer works, the glass beneath still transfers heat efficiently.

Why transparent wood is appealing

Transparent wood has gained attention because wood starts with useful traits for buildings. It is strong for its weight and naturally resists heat flow better than glass. Its internal channels also form a ready-made scaffold that can be filled with polymers that transmit light.

Natural wood is not clear because light scatters in its porous structure and lignin absorbs light. Lignin also gives wood its brown color. A common strategy is to chemically modify or remove some lignin and then fill the remaining structure with a polymer whose refractive index closely matches wood components. That reduces scattering and improves clarity.

The Korean team aimed to add two functions often treated separately: switching transparency with temperature and shielding ultraviolet radiation. Instead of layering extra UV-absorbing parts onto a window, the researchers sought UV blocking from the composite itself.

How the material was built

The team tested balsa, bass and pine. Each sample was cut into small slices aligned with the growth direction. The slices underwent a chemical treatment to modify lignin and bleach the wood, leaving a pale template with its hollow structure still intact.

After bleaching, the researchers infiltrated the wood with a UV-curable polymer called NOA 63. This polymer cures quickly under UV light and has high optical transparency. The team also made epoxy-filled versions for comparison.

"NOA 63 produced clearer transparent wood than epoxy in these tests. Microscopy showed NOA 63 filled voids and cell walls without obvious gaps. The epoxy versions showed cracks or gaps at interfaces, likely from shrinkage during curing. Those gaps scatter light and reduce clarity," Kim explained to The Brighter Side of News.

"Our work also tracked mechanical performance. Polymer infiltration improved tensile stress for all three woods. Epoxy versions reached higher tensile stress, but the NOA 63 versions still strengthened substantially and offered better optical performance," he further shared.

Adding temperature switching with liquid crystals

The key advance came from introducing polymer-dispersed liquid crystals, or PDLCs, into the wood. PDLC materials can scatter light in one state and transmit it in another. Here, the switching depends on temperature rather than electricity.

The liquid crystal used was 4-cyano-4′-n-octylbiphenyl, called 8CB. The team mixed 8CB into NOA 63, then infiltrated the bleached wood with that mixture and cured it under UV light. The resulting composite is described as PDLC/TW, meaning transparent wood filled with the PDLC mixture.

In practical terms, the panel is designed to become clearer in warmer conditions and more opaque in cooler conditions. That could support natural light during the day and privacy at night without added power.

The study reports strong changes in visible-light transmission at 550 nanometers. Balsa PDLC/TW switched from 28% transmittance at room temperature to 78% at 40 degrees Celsius. Bass rose from 14% to 82%, and pine rose from 33% to 73%.

Microscopy and thermal measurements linked the switching to phase changes in 8CB. At lower temperatures, the liquid crystal phase produces refractive index mismatch and light scattering. At higher temperatures, the liquid crystal becomes isotropic and better matches the polymer, allowing light to pass with less scattering.

UV shielding and insulation, not just light control

One of the study’s headline claims is near-total shielding of UVA light in the 320 to 400 nanometer range for some versions. At room temperature, opaque balsa and bass PDLC/TWs blocked almost 100% of UVA. Even when heated to 40 degrees Celsius and becoming transparent, they still shielded most UVA.

The team argues this UV blocking arises from an interaction between 8CB and modified lignin, described as a “J-aggregation” effect. Pine PDLC/TW showed weaker UV absorbance and degraded more under extended UV exposure, which the authors linked to lignin-related darkening.

The composite also acts as a strong thermal barrier. PDLC/TW showed thermal conductivity of 0.197 W m⁻¹ K⁻¹, compared with 0.911 W m⁻¹ K⁻¹ for glass. “With a thermal conductivity of 0.197 W m⁻¹ K⁻¹, our novel bio-composite is nearly five times more insulating than conventional glass, significantly slowing heat loss or gain in buildings,” highlights Dr. Kim.

In a model-house heat test, a glass house warmed from about 20.85 degrees Celsius to 40.23 degrees Celsius in four minutes. A PDLC/TW house took 10 minutes to reach the same peak, suggesting slower heat transfer.

The team also demonstrated cycling stability. Balsa PDLC/TW kept visible-light modulation after 100 heating and cooling cycles, according to the study.

Practical Implications of the Research

If the performance scales to larger panels and real buildings, the work points to windows that regulate light and privacy without electricity. That could reduce demand for powered smart-window systems and cut energy use tied to heating and cooling.

The UV shielding may also protect indoor materials from fading and lower human UV exposure near windows. In agriculture, smart greenhouse panels could limit overheating and crop scorching while keeping stable growing temperatures, potentially helping food production in harsher climates.

The team also highlights health uses beyond buildings. “Our innovation is a direct, eco-friendly replacement for glass that provides privacy at night and natural illumination during the day while slashing HVAC energy costs. It is ideal for smart greenhouses to prevent crop scorching by automatically regulating sunlight and maintaining stable internal growing temperatures. Furthermore, the present technology is promising for the development of intelligent wearable health monitors. It can be used as a flexible skin patch that turns transparent when body temperature exceeds 38°C, providing an instant visual health alert without the need for batteries or electronics,” says Dr. Kim.

If researchers can improve durability, cost, and manufacturing scale, the approach could support low-cost, battery-free indicators for simple health monitoring, while expanding the toolbox for bio-based building materials.

Research findings are available online in the journal Advanced Composites and Hybrid Materials.

Related Stories

- Transparent wood looks to revolutionize home construction and personal electronics

- Transparent wood promises to become the window to the future?

- Scientists develop the first-ever eco-friendly, biodegradable, biorecyclable glass

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.

Shy Cohen

Writer