Scientists reveal how dark matter formed in the early universe and why its still here

A new study finds dark matter could have formed at near light speed and still cooled enough to build galaxies.

Edited By: Joshua Shavit

Edited By: Joshua Shavit

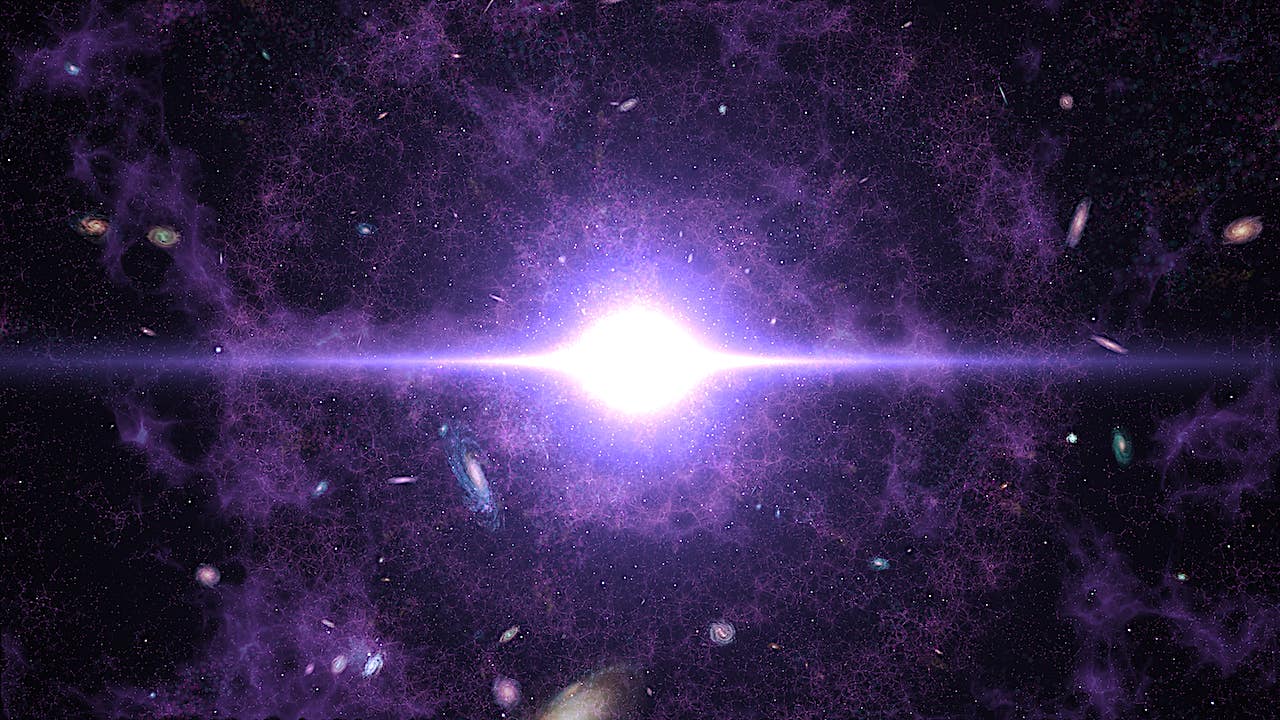

Dark matter may have started hot and cooled during reheating after the Big Bang. (CREDIT: NASA / Goddard Space Flight Center Conceptual Image Lab)

Researchers from the University of Minnesota Twin Cities and Université Paris-Saclay have reopened one of cosmology’s oldest debates by showing that dark matter may have started its life far hotter than anyone expected.

The work, led by Stephen Henrich, a graduate student in the School of Physics and Astronomy at Minnesota, and co-authored by Keith Olive and Yann Mambrini, appeared in Physical Review Letters, the flagship journal of the American Physical Society. Their study suggests that dark matter could have formed while moving close to the speed of light and still cooled enough to help build galaxies.

For decades, most physicists believed dark matter had to be cold at birth. Cold, in this case, means slow moving. That idea came from how galaxies and clusters form. If dark matter were too fast, it would smear out small structures and prevent stars and galaxies from clumping. The new work challenges that view by focusing on a forgotten chapter in the early universe, a period known as post inflationary reheating.

Rethinking how dark matter first appeared

Inflation is the brief burst of rapid expansion thought to have happened just after the Universe began. When inflation ended, its energy did not turn into matter and radiation all at once. Instead, it likely took time, as the inflation field slowly decayed into particles. That era is called reheating. Henrich and his colleagues show that what happens during reheating can change how dark matter forms.

“Dark matter is famously enigmatic. One of the few things we know about it is that it needs to be cold,” Henrich told The Brighter Side of News. “As a result, for the past four decades, most researchers have believed that dark matter must be cold when it is born in the primordial universe. Our recent results show that this is not the case; in fact, dark matter can be red hot when it is born but still have time to cool down before galaxies begin to form,” he continued.

The team studied a process they call ultra relativistic freeze out, or UFO. In simple terms, it means dark matter stops interacting with ordinary matter while it is still moving extremely fast. Even so, the Universe keeps expanding and cooling. By the time galaxies start to form, those once fast particles have slowed enough to behave like cold dark matter.

Lessons from neutrinos and a twist on an old idea

This idea has a historical echo. Neutrinos, the light and elusive particles that stream through Earth, decoupled from matter while still moving at near light speed. That happened because the Universe expanded faster than neutrinos could keep colliding. As Olive explains, this was once thought to rule out neutrinos as dark matter.

“The simplest dark matter candidate, a low mass neutrino, was ruled out over 40 years ago since it would have wiped out galactic size structures instead of seeding it,” Olive said. “The neutrino became the prime example of hot dark matter, where structure formation relies on cold dark matter. It is amazing that a similar candidate, if produced just as the hot big bang universe was being created, could have cooled to the point where it would in fact act as cold dark matter.”

The difference, the new study shows, lies in timing. If dark matter decouples during reheating, not after the Universe has fully filled with radiation, it has extra time to lose energy as space stretches. That allows even light, fast particles to become slow enough before galaxies take shape.

Why this matters for today’s dark matter searches

Modern experiments have struggled to find dark matter. The most famous idea, the WIMP or weakly interacting massive particle, depends on dark matter freezing out when it is already slow and heavy. But detectors looking for WIMPs have not seen clear signals. Another idea, the FIMP or feebly interacting massive particle, makes dark matter so weakly connected to normal matter that it is almost impossible to detect.

The UFO picture sits between those two extremes. It offers a wide middle ground where dark matter can briefly reach balance with the early universe and then freeze out while still hot. For some kinds of interactions, especially those involving heavy mediator particles, this middle zone becomes large and natural.

The study also shows that, under realistic reheating conditions, dark matter with a mass above a few thousand electron volts would be cold enough by the time the Universe cooled to about one electron volt, the era when cosmic structure begins to grow. That meets the strict limits from galaxy surveys and cosmic background measurements.

Opening a new window on the early universe

Beyond explaining dark matter, the work hints at a deeper prize. “With our new findings, we may be able to access a period in the history of the Universe very close to the Big Bang,” said Mambrini, a professor at Université Paris-Saclay. That period has remained mostly out of reach because it happened so early and left so few direct traces.

The team now plans to explore how these UFO dark matter particles might be detected, either in collider experiments, scattering studies, or through subtle signals in the sky. Their work was supported by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 program through a Marie Sklodowska Curie grant.

By showing that dark matter did not have to be born cold, the study widens the map of what is possible. It suggests that a large and long ignored region of dark matter theory may hold the answer to one of science’s biggest mysteries.

Practical Implications of the Research

The findings reshape how scientists think about dark matter’s origin and how it might be found. If dark matter formed through ultra relativistic freeze out during reheating, then many models once set aside become viable again.

That gives physicists more targets to test in particle accelerators and in cosmic surveys. It also improves the odds of spotting dark matter indirectly through its effects on galaxies or the early universe.

In the long run, a better grasp of dark matter will sharpen models of cosmic evolution, from the first atoms to the largest galaxy clusters, helping humanity understand where it came from and how the Universe took its present form.

Research findings are available online in the journal Physical Review Letters.

Related Stories

- Runaway stars within the Milky Way may reveal dark matter’s hidden structure

- Cloud-9: Astronomers spot a gas-rich cloud dominated by dark matter that contains no stars

- Fusion reactors may be the key to uncovering dark matter particles

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.

Joseph Shavit

Writer, Editor-At-Large and Publisher

Joseph Shavit, based in Los Angeles, is a seasoned science journalist, editor and co-founder of The Brighter Side of News, where he transforms complex discoveries into clear, engaging stories for general readers. With vast experience at major media groups like Times Mirror and Tribune, he writes with both authority and curiosity. His writing focuses on space science, planetary science, quantum mechanics, geology. Known for linking breakthroughs to real-world markets, he highlights how research transitions into products and industries that shape daily life.