Superionic form of water may power planetary magnetic fields

Experiments using powerful X-ray lasers show that superionic water forms a complex, disordered structure under extreme pressure, reshaping models of icy planets.

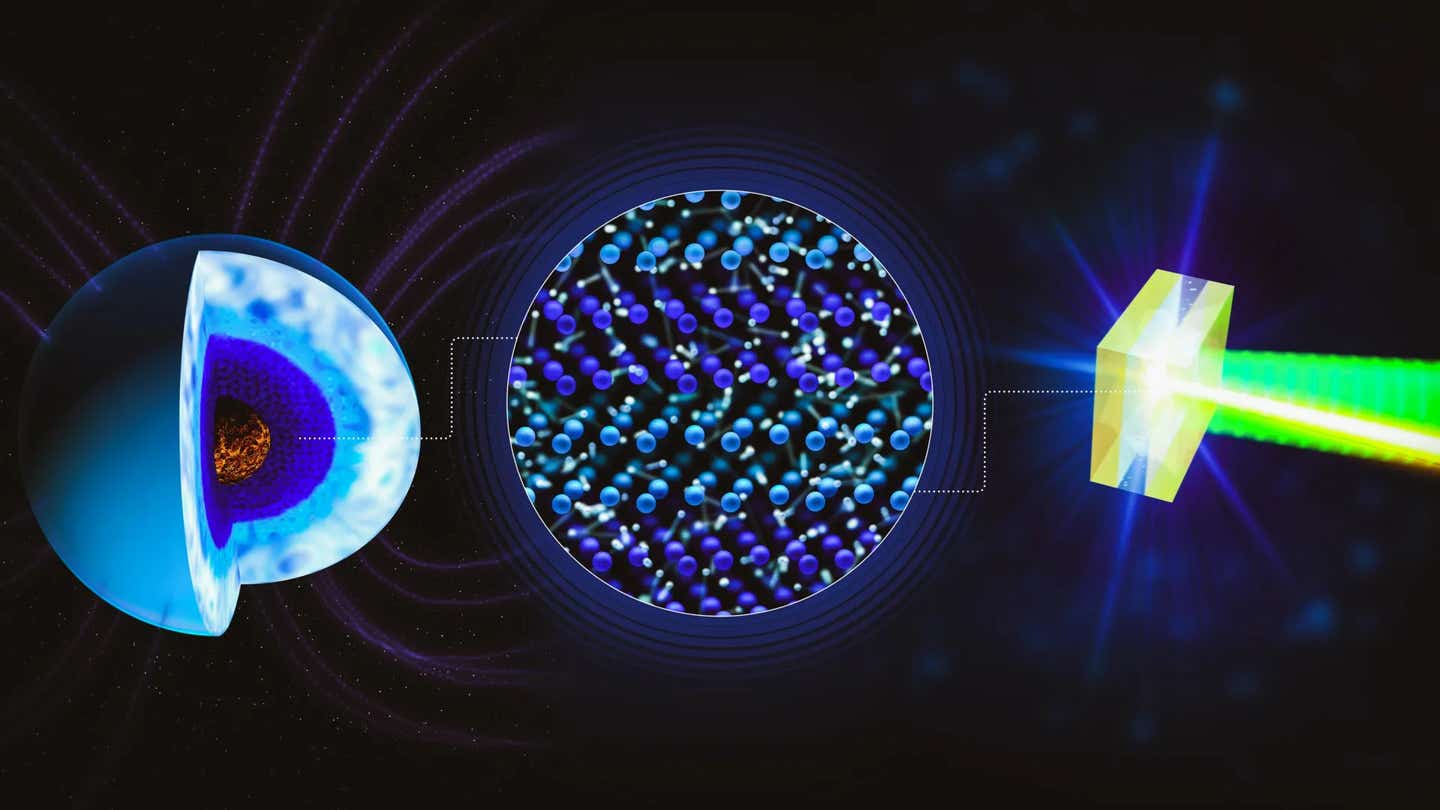

A schematic of superionic water, where oxygen atoms form a solid lattice and hydrogen ions move freely. Powerful lasers allow this planet-like state to be recreated and measured in the lab. (CREDIT: Greg Stewart / SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory)

Water doesn't behave the same way in a glass as it does as ice in your freezer. When water is heated to several thousand degrees Celsius, it is also placed under pressures many millions of times greater than the pressure of Earth’s atmosphere; the result is the special form called "superionic water". The superionic form of water has a rigid, solid-like crystal structure composed of oxygen atoms with flowing hydrogen ions moving through that structure. As such, superionic water can conduct electricity very well.

Researchers from the U.S. and various countries in Europe who work at X-ray laser facilities are now beginning to understand that the superionic form of water is actually a lot more complicated than previously thought. Their work helps to explain the unusual magnetic fields seen in other planets, such as Uranus and Neptune, that are believed to be composed of enormous reservoirs of water located deep inside those planets.

The research used the Matter in Extreme Conditions (MEC) instrument from the Linac Coherent Light Source at the U.S. Department of Energy and the HED-HIBEF instrument from the European XFEL.

An Ongoing Argument in Science

There has been an ongoing debate in the scientific community for several years regarding how the oxygen atoms arrange themselves in superionic water. The first set of solutions proposed was based on the idea that a body-centered cubic (bcc) arrangement was likely to develop at high pressures, similar to how some of the higher-pressure ice structures develop.

Then, computer simulations showed that a face-centered cubic (fcc) structure was actually more stable at higher pressures than was predicted by the first set of solutions. The distinction between BCC and FCC is critical because the movement of hydrogen ions, which happens as a result of electrical conductivity, is affected by the arrangement of the oxygen atoms.

The final solution set goes beyond the previously proposed arrangement solutions and suggests that the arrangement of superionic water may not settle into a single orderly pattern at all. Oxygen atoms have the potential to form a mix of FCC and HCP structures by stacking themselves in a nonuniform way instead of stacking perfectly. When this occurs, structural disorder occurs wherein the atomic layers form different patterns and do not repeat in a neatly ordered way.

To Achieve Planetary Conditions on Earth

Laboratory testing of these ideas is challenging, as the extreme pressure and temperature conditions that exist naturally on ice giant planets are greater than 100 GPa (Gigapascals) in pressure and 2000 K (Kelvin) in temperature, far beyond the capabilities of any modern laboratory instruments.

"Because of the brief duration of time that extreme conditions last, any experiment that has been performed using traditional techniques has returned conflicting outcomes or indications of structural disorder because they last only a small fraction of a second," Professor M. G. Stevenson, corresponding study author from the University of Rostock, told The Brighter Side of News.

"Our research overcomes these challenges through the application of powerful laser-generated shock waves compressing water when combined with probing the water using ultrafast X-ray pulses that exist only for a trillionth of a second. This combination has permitted our team to gather multiple detailed images of the atomic arrangement of water while it is in a superionic state," he continued.

What the Experiments Revealed

The information obtained from the experiments indicates that above approximately 150 GPa of pressure and approximately 2450 K in temperature, the primary structure formed by oxygen atoms is FCC. Also, the experimental results indicate that there is no indication of any BCC structure existing at these high-pressure environments. These results substantiate the previous shock wave experiments and eliminate the possibility that BCC is stable at these very high-pressure levels.

However, there is still a larger portion of the data that is not yet definitively explained. The patterns of x-ray diffraction from the sample under high-pressure conditions reveal the clear presence of stacking disorder rather than a completely ordered FCC crystal structure. Research into the structure of superionic water has revealed that the layers of oxygen in superionic water contain both FCC (face-centered cubic) and HCP (hexagonal close-packed) layers mixed together.

Approximately 25 - 32% of the layers of oxygen were found to display an HCP stacking pattern. These findings agree with predictions made using state-of-the-art computer simulations, which have indicated that superionic water may exist in a number of closely-related structural forms due to competition between several of these forms at this point in the structural evolution of the structure.

Although there were still slight differences between the calculated and measured structures, these differences suggest that the true structure of the superionic water is much more complex than can be represented by the existing model(s).

The Wider Phase Picture

As the researchers adjusted their laser pulse intensity and timing to generate a range of conditions in the high-pressure regime (7 to 120 GPa), it was found that both FCC and BCC (body-centered cubic) forms of structure were present in combination within this pressure range, thereby demonstrating that the FCC and BCC forms have almost equal stability in these conditions; hence both forms can coexist.

Under much lower pressure conditions than those mentioned above (25 - 50 GPa, < 1300 K), the superionic water was shown to exist as a BCC structure, supported by numerous unique diffraction peaks found in the data collected for this phase.

The densities of this phase matched previous measurements of the density of the BCC phase of ice (H2O). Taken together, these results provide a coherent view of the structural transformations that take place in superionic water when subjected to increasing temperature and pressure.

The Importance of Disorder

The remaining unanswered question is whether the disorder observed in the stacking of superionic water is an intrinsic property of this phase of water or a result of the rapid shock-induced compressive forces acting on it.

Should the disorder be an intrinsic property of superionic water, there are likely to be wide-ranging implications for the physical properties of superionic water, including its viscosity and electrical conductivity. It should be noted that the electrical conductivity of superionic water is believed to significantly influence the thermal transport and magnetic field generation in planets.

In contrast, should the stacking disorder be an artefact of the shock compression process and, therefore, of limited long-term significance while under the state of prolonged stability that is reached when the superionic water is under the conditions of the deep interior of a planet, the implications of these findings depend on how long the disorder remains under planetary conditions. Either way, the results demonstrate that superionic water is a phase with a more complex "landscape" of competing structures and fine atomic motions.

Application of the Research

An understanding of the behavior of superionic water can provide scientists with a basis for the development of models of the interiors of superoxide planets, which are plentiful in the Universe as we know it. Improved models of the electrical conductivity and flow of superionic water should provide many scientists with insight into how the unusual magnetic fields present on superoxide planets have developed and how they maintain their existence.

The research carried out in the context of this project can also be used to enhance materials science by providing an improved understanding of how simple forms of matter behave when subjected to extreme conditions, which will be beneficial in designing new materials.

Finally, the research adds to our knowledge of how matter can exist under extreme conditions that are not achievable naturally at the surface of the Earth, thereby extending the frontiers of chemistry and physics.

Research findings are available online in the journal Nature Communications.

Related Stories

- Scientists discover new form of ice that freezes at room temperature

- Titan’s interior is slushy ice, not a hidden ocean, Cassini data finds

- Venus's clouds contain massive reservoirs of water and iron

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.

Joseph Shavit

Writer, Editor-At-Large and Publisher

Joseph Shavit, based in Los Angeles, is a seasoned science journalist, editor and co-founder of The Brighter Side of News, where he transforms complex discoveries into clear, engaging stories for general readers. With vast experience at major media groups like Times Mirror and Tribune, he writes with both authority and curiosity. His writing focuses on space science, planetary science, quantum mechanics, geology. Known for linking breakthroughs to real-world markets, he highlights how research transitions into products and industries that shape daily life.