The Milky Way’s stars reveal a hidden history of two galaxies in one

New simulations show why the Milky Way’s stars split into two chemical groups and reveal a new view of galactic evolution.

Edited By: Joshua Shavit

Edited By: Joshua Shavit

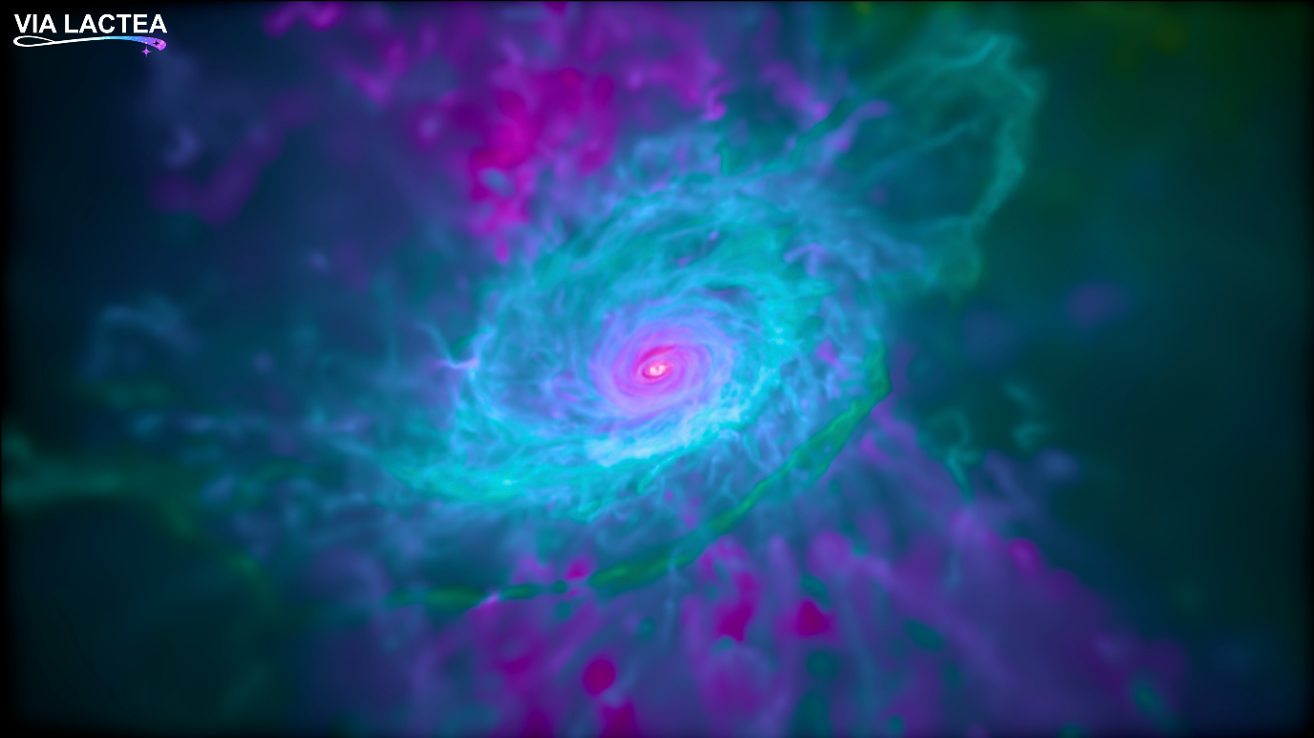

This image shows the gas disc in a computer simulation of a Milky Way-like galaxy from the Auriga suite. Colours represent the ratio of magnesium (Mg) to iron (Fe), revealing that the galactic centre (pink) is poor in Mg, while the outskirts (green) are Mg-rich. These chemical patterns provide important clues about how the galaxy formed. (CREDIT: Matthew D. A. Orkney (ICCUB-IEEC) /Auriga project)

From your place inside the Milky Way, you are living within a galaxy that keeps a detailed chemical diary. Every star holds clues about when it formed and what the galaxy was like at the time. Over the past decade, data from the Gaia space telescope and massive sky surveys have given astronomers an unusually sharp view of those records. With millions of stars tracked for motion, age and composition, a strange pattern has stood out: the stars in the Milky Way’s disc do not follow one smooth chemical trend.

Instead, they fall into two main groups. When astronomers measure iron and magnesium inside stars, they find that one group has much more magnesium compared with iron, while the other does not. These two families overlap in iron content, yet they separate cleanly when magnesium is factored in. This striking split, known as chemical bimodality, has raised a central question. Is this feature common across galaxies, or is the Milky Way unusual?

A new study in Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society sets out to answer that. The research used advanced computer simulations to replay the formation of galaxies like ours across billions of years. The goal was to learn what causes these chemical tracks and whether major galaxy crashes or slow star birth play the leading role.

Thick and Thin Discs, One Big Question

Astronomers already know that the Milky Way has two main layers: a thick disc and a thin disc. The thicker layer sits farther above and below the galaxy’s center and mostly contains very old stars. The thinner layer is flatter and is still making new stars today. These shapes line up with chemistry as well. The high magnesium stars mostly live in the thick disc, while the lower magnesium stars tend to stay close to the galaxy’s plane.

For years, scientists suspected that a violent collision shaped this pattern. Evidence from the Milky Way’s outer stars shows that our galaxy merged with a smaller neighbor called Gaia-Sausage-Enceladus about nine billion years ago. The idea was simple. The crash might have dumped fresh gas into the galaxy, changed its chemistry and sparked a new generation of stars with a different chemical mix.

But the new findings point in a different direction.

Running Galaxies on a Computer

The research team relied on a suite of galaxy simulations known as Auriga. These digital models followed the growth of 30 galaxies similar in size to the Milky Way, starting when the universe was still young. Inside each simulation, gas flowed in, stars ignited and supernovas scattered new elements into space. Over time, dark matter and glowing stars shaped each galaxy’s form.

To study chemical patterns, the scientists focused on magnesium as a marker for fast exploding stars, while iron traced slower stellar deaths. The balance between the two says a lot about how quickly stars formed. When birth rates are high, magnesium rises fast. When star making slows, iron catches up.

After sorting millions of simulated stars by age, motion and location, the team found something surprising. Roughly half the galaxies developed two clear chemical tracks like the Milky Way. The rest followed very different paths. Some had one track. Others had several. A few showed a blurry spread with no clean pattern at all.

“This study shows that the Milky Way’s chemical structure is not a universal blueprint,” said lead author Matthew Orkney of the Institute of Cosmos Sciences at the University of Barcelona and the Institut d’Estudis Espacials de Catalunya. “Galaxies can follow different paths to reach similar outcomes, and that diversity is key to understanding galaxy evolution.”

Mergers Matter Less Than Expected

If galaxy crashes caused chemical splits, the models should have shown a clear link. They did not. Some galaxies with major mergers formed two chemical groups. Others with similar crashes never developed that pattern. Even more striking, a few systems with no big collisions still formed clean chemical pairs.

When the team measured how much merger gas actually fed star formation, the numbers were small. In a galaxy resembling the Milky Way’s major merger, the incoming gas made up less than 15 percent of the stars in the high magnesium group and under 10 percent in the lower magnesium group. Even the largest collisions altered metallic levels by only small amounts.

The message was clear. Mergers can shake a galaxy and heat its stars, but they do not control its chemical identity.

Star Birth Sets the Rhythm

So what does? The models point to the pace of star formation as the main driver.

Every galaxy that showed two chemical groups shared one trait. Early in its life, the galaxy formed stars at a frantic rate. Magnesium built up fast from massive, short lived stars. Then star formation slowed or stopped for a time. During this pause, iron from slower explosions continued to rise in the gas. When star birth resumed, the new stars formed in a very different chemical setting.

This two stage process naturally produced two tracks. The gap between them lined up with the same pause in star formation. In many simulated systems, the lower magnesium stars did not appear until about nine billion years ago.

The study also found that gas flowing in from outside the galaxy played a bigger role than gas from mergers. A vast halo of thin material, called the circumgalactic medium, surrounds every large galaxy. This reservoir feeds the disc slowly, even today. Because this gas stays low in metals, it helps shape the chemistry of later generations of stars.

When a galaxy’s disc is thick and turbulent, this external gas forms stars in many places, which spreads out metallic content. When the disc settles into a thin, calm layer, mixing becomes more even and chemical ranges narrow.

What It Means for the Milky Way

The results suggest a new story for our home galaxy. The thick disc likely formed during a chaotic youth filled with gas and fast star birth. That phase created the high magnesium group. Then came a quieter era. Only later did the thin disc grow, fed mostly by gas drifting in from the galaxy’s outer regions, not by crash debris.

The famous ancient merger still matters. It likely stirred the galaxy and added shape to its structure. Yet it did not rewrite the Milky Way’s chemistry. The elements tell a quieter story about timing, not trauma.

“This study predicts that other galaxies should exhibit a diversity of chemical sequences,” said Dr. Chervin Laporte of ICCUB-IEEC, CNRS-Observatoire de Paris and Kavli IPMU. “This will soon be probed in the era of 30m telescopes where such studies in external galaxies will become routine.”

As new instruments like the James Webb Space Telescope and upcoming missions such as PLATO and Chronos scan distant stars, astronomers will test these ideas beyond the Milky Way. Each galaxy will add another chapter to a larger story.

In the end, a galaxy’s past is written not only in its shape, but in its atoms. The Milky Way did not become what it is through one crash, but through many seasons of star birth and silence.

Research findings are available online in the journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

Related Stories

- Scientists create the world’s first Milky Way simulation following 100 billion stars over 10,000 years

- Pulsars or dark matter? The Milky Way’s central glow just got more puzzling

- Scientists crack the mystery of galactic filaments and magnetic fields at the heart of the Milky Way

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.

Joseph Shavit

Writer, Editor-At-Large and Publisher

Joseph Shavit, based in Los Angeles, is a seasoned science journalist, editor and co-founder of The Brighter Side of News, where he transforms complex discoveries into clear, engaging stories for general readers. With vast experience at major media groups like Times Mirror and Tribune, he writes with both authority and curiosity. His writing focuses on space science, planetary science, quantum mechanics, geology. Known for linking breakthroughs to real-world markets, he highlights how research transitions into products and industries that shape daily life.