The seven-hour flash: Astronomers discover the longest gamma-ray burst on record

A record-breaking gamma-ray burst forces astronomers to rethink how black holes form and how jets stay active for hours.

Edited By: Joshua Shavit

Edited By: Joshua Shavit

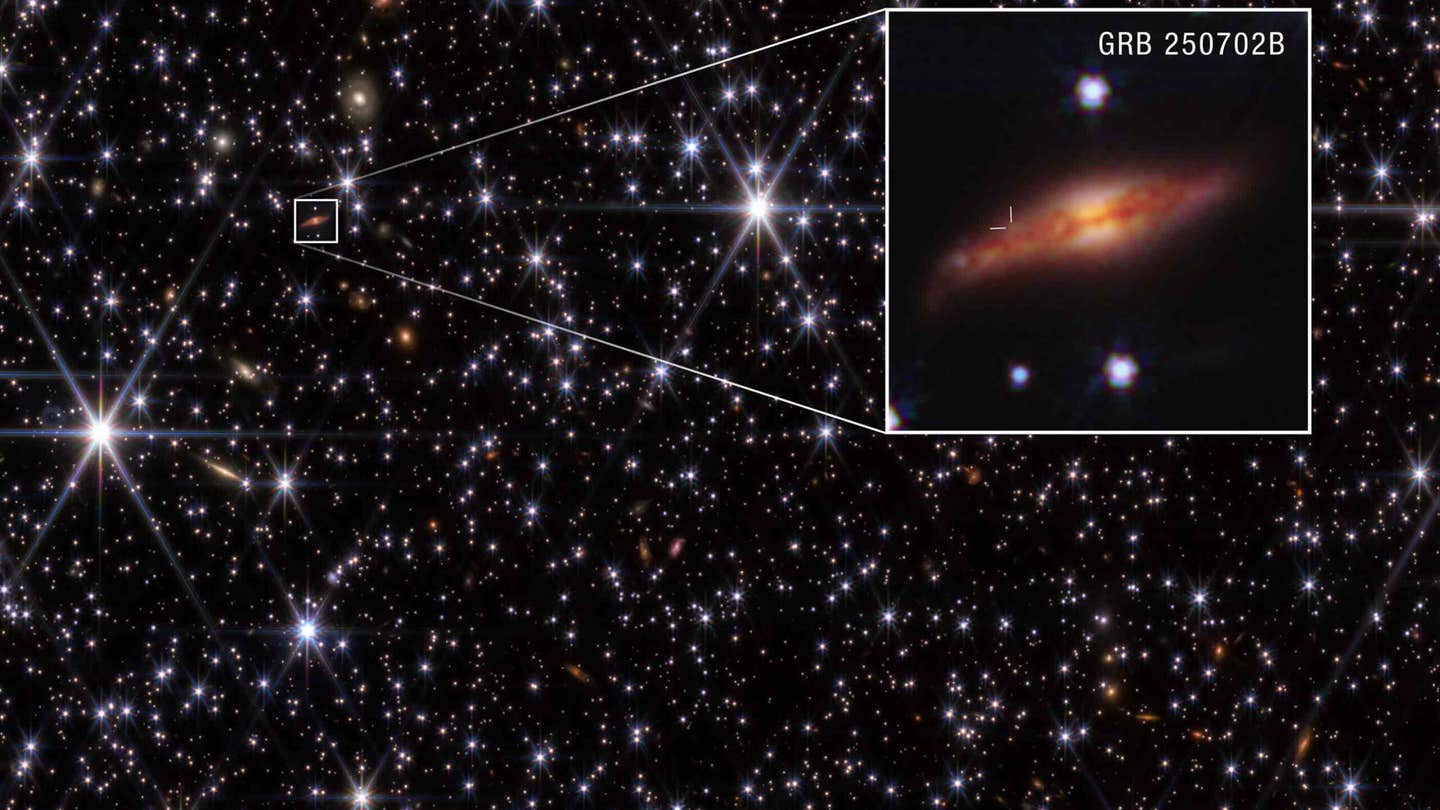

On Oct. 5, NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope gave astronomers their clearest view of GRB 250702B’s host galaxy, which is so far away its light takes about 8 billion years to reach us. (CREDIT: NASA, ESA, CSA, H. Sears (Rutgers))

Astronomers spend careers watching stars collapse and explode, but an eruption spotted in July pushed beyond anything seen before. The event, called GRB 250702B, released high-energy radiation for nearly seven hours. That endurance broke every known record for its kind and forced scientists to rethink how such blasts are powered.

Gamma-ray bursts are brief, fierce flashes from distant galaxies. Most last seconds, sometimes minutes. This one glowed for more than 25,000 seconds. The previous record holder lasted about 15,000 seconds. By that measure alone, this outburst changed the scale.

NASA’s Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope first flagged the signal on July 2. The detector triggered again and again over about three hours. At first, the alerts looked like a chain of separate flares. Other spacecraft soon confirmed a single source. Telescopes on Earth then joined in, tracking radiation across X-rays, near-infrared light, and radio waves. No normal visible light appeared.

“This is certainly an outburst unlike any other we have seen in the past 50 years,” said Eliza Neights, an astronomer at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Maryland.

Pinpointing the blast

NASA’s Swift satellite narrowed the burst to a tiny patch of sky. Images from the Hubble Space Telescope and the European Southern Observatory’s Very Large Telescope revealed its host galaxy. The location did not sit in the galaxy’s center, which ruled out a common idea. If a star had been torn apart by a massive black hole, the flare would have come from the core.

Instead, the afterglow told a different story. Its fading pattern matched shock waves from a razor-thin jet of matter moving near light speed. That profile fits traditional gamma-ray bursts, which fire jets as a newborn black hole or neutron star feeds on falling debris.

The James Webb Space Telescope then measured the galaxy’s distance. The light left the scene when the universe was about half its current age, roughly eight billion years ago. The site lies in a region busy with star birth, which favors violent ends for heavy stars.

What astronomers did not see mattered just as much. A normal, long gamma-ray burst often brings a bright supernova weeks later. Careful searches found no clear trace. If an explosion occurred, it must have been faint, dusty, or oddly weak.

A marathon of radiation

Researchers blended data from five space missions to reconstruct the timeline. Gamma rays arrived long after midnight on July 2, by universal time, and kept coming for hours. Once scientists corrected for the expansion of the universe, the blast still burned for more than 12,500 seconds in its own frame. No known type had ever run so long.

The light curve showed rapid flickers inside the drawn-out glow. Some spikes lasted only about a second. In the source’s frame, that shrank to about half a second. Such quick shifts reveal a compact engine. A giant black hole changes too slowly. A stellar-sized black hole fits the bill.

Despite its length, the outburst was not wildly powerful. Its total energy matched other strong gamma-ray bursts. It simply spent that energy slowly, researchers found. Peak brightness also looked ordinary once we counted how tightly the jet was aimed.

Its spectrum added another twist. High and low energy photons arrived almost together, which is rare for long events. Even stranger, the peak energy was high, with photons topping several million electron volts. Calculations showed the jet must have raced with extreme speed, at least 56 times faster than would be safe under everyday physics rules.

“Only through the combined power of instruments on multiple spacecraft could we understand this event,” said Eric Burns, an astrophysicist at Louisiana State University.

Ruling out familiar causes

Teams tested every likely culprit. Mergers of neutron stars fail to last that long. Magnetic stars flare too briefly. White dwarf pairs cannot sustain such power. Tidal shredding by a supermassive black hole did not work, since the flare sat away from the galactic center and varied too fast.

Even the standard model for long bursts struggled. In that scenario, a massive star collapses and feeds a jet as it spins. But no single star holds enough spin to run a jet for tens of thousands of seconds. The math refused to cooperate.

One idea survived.

The favored model involves a helium star and a compact partner. A stripped star rich in helium orbits a black hole or a neutron star. The compact object spirals inward, stirring the star into a frantic spin. When it hits the core, a thick disk of debris forms and funnels material into the compact object. The disk’s borrowed spin keeps the jet alive far longer than any lone star could manage.

The theory also explains why the outburst peaked late. Observations show activity up to nearly a day when early X-rays are counted. The gamma rays took tens of thousands of seconds to reach full strength, just as the merger model predicts.

It may also explain the missing supernova. These mergers should create little radioactive nickel, the fuel that makes supernovae glow. Without it, the blast would dim quickly and hide in dust.

NASA even released an animation that matches this picture, with a black hole about three times the sun’s mass and an event horizon only 11 miles across closing in on a helium star.

What Webb revealed

A Rutgers University team used Webb’s main infrared camera to inspect the host galaxy months later. The images first suggested either two galaxies colliding or one split by dark dust.

“In such vibrant and unprecedented detail, we see just one very large galaxy with a dust lane,” said Huei Sears, a postdoctoral researcher at the Rutgers School of Arts and Sciences. “The galaxy has such a complex structure that it’s not 100% clear if there’s anything left to see of the explosion, but if there is, it’s really faint.”

That weak remnant fits a gamma-ray burst better than a star consumed by a gargantuan black hole. Still, Sears urges caution.

“We have only seen a few tidal events of this type, so we don’t know for sure how they evolve,” she said. “A lot of studies provide different explanations. It’s still early in our understanding.”

What comes next

If GRB 250702B truly marks a helium star merger, it points to a rare class of cosmic disaster. These events should trace regions where stars are born and need not prefer thin, metal-poor galaxies. That widens the search.

They are also easy to miss. Some satellites cannot stare at one patch for hours. Earth’s shadow interrupts others. This burst was caught only because far-flung instruments watched without blinking.

"After more than fifteen thousand gamma-ray bursts have been detected by astronomers, this one stands out. It looks familiar but refuses old limits. The cosmos, it seems, still holds surprises for us", Huei Sears told The Brighter Side of News.

Practical implications of the research

The findings expand how scientists explain the deaths of massive stars and the birth of black holes. A confirmed helium star merger model would add a new channel for creating black holes and launching jets.

That improves forecasts for how often extreme explosions occur across cosmic history. It also sharpens strategies for future missions, encouraging longer, uninterrupted monitoring to catch ultra-long events.

Better detection increases chances of linking gamma-ray bursts with gravitational waves, which could reveal how often compact objects merge.

Over time, this work may refine how astronomers measure distances, chart star formation, and test physics under extreme conditions.

Research findings are available online in the journal arXiv.

Related Stories

- Rare black hole-star merger creates the longest gamma-ray burst ever

- Gamma-rays trigger lightning and alter atmospheric chemistry

- The extraordinary cause of the brightest gamma-ray burst of all time

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.

Joseph Shavit

Writer, Editor-At-Large and Publisher

Joseph Shavit, based in Los Angeles, is a seasoned science journalist, editor and co-founder of The Brighter Side of News, where he transforms complex discoveries into clear, engaging stories for general readers. With vast experience at major media groups like Times Mirror and Tribune, he writes with both authority and curiosity. His writing focuses on space science, planetary science, quantum mechanics, geology. Known for linking breakthroughs to real-world markets, he highlights how research transitions into products and industries that shape daily life.