Tidal discovery offers new insight into how ‘hot Jupiters’ formed

New research from the University of Tokyo uses tidal timing to identify hot Jupiters that moved inward through calm disk migration.

Edited By: Joshua Shavit

Edited By: Joshua Shavit

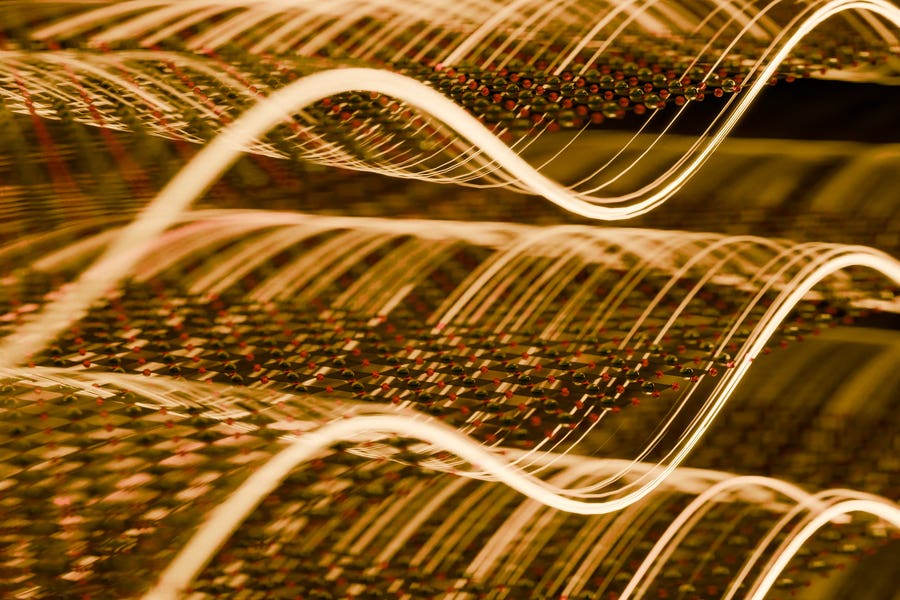

An illustration of a Jupiter mass planet migrating through a protoplanetary disk. (CREDIT: Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, College of Arts and Sciences, The University of Tokyo)

Hot Jupiters rank among the strangest planets astronomers have ever found. They are gas giants as massive as Jupiter, yet they race around their stars in just a few days. Since the first such world was discovered in 1995, scientists have agreed on one point. These planets almost certainly formed far from their stars, where gas giants can grow, and later moved inward. The unresolved question has been how that journey happened.

Two ideas dominate the debate. In one, known as disk migration, a young planet drifts inward while still embedded in the thick disk of gas and dust that surrounds a newborn star. In the other, called high eccentricity migration, a planet’s orbit becomes stretched and distorted after a gravitational shove from another planet or a companion star. Over time, strong tides raised during close passes then smooth that orbit into a tight, nearly circular path close to the star.

For years, researchers have tried to tell these stories apart using clues such as the tilt between a planet’s orbit and its star’s spin. The problem is that tides can erase those clues. A calm, aligned orbit today does not always mean a calm past.

A new study led by PhD student Yugo Kawai and Assistant Professor Akihiko Fukui at the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, the University of Tokyo, offers a different approach. Instead of asking what an orbit looks like now, the team asks whether there has been enough time for a violent path to work at all.

Timing migration with tidal physics

The study focuses on a simple physical clock. When a planet follows an elongated orbit, tides raised within the planet act to make that path more circular. The time required for this process is called the circularization timescale. It depends on measurable properties such as the planet’s mass, size, and distance from its star. It also depends on how efficiently the planet dissipates tidal energy, captured in a quantity known as the tidal quality factor.

In the high eccentricity picture, a planet must complete this circularization before today. That means its circularization time must be shorter than the age of the system. If the calculated timescale is longer than the system’s age, then tides simply have not had enough time to erase a once elongated orbit. A planet in that situation, yet already moving on a nearly circular path, becomes a strong candidate for disk migration.

To apply this test, the researchers first needed a realistic value for the tidal quality factor of hot Jupiters. Jupiter’s own value likely falls between about 60,000 and two million, but alien worlds may differ. The team treated this factor as adjustable and searched for the value that best separated planets that should still look eccentric from those that should already be circular.

Building a large and careful sample

The analysis draws on a large census of known giant planets. The team selected worlds with masses between 0.2 and 13 times that of Jupiter, radii larger than five Earth radii, and orbital periods shorter than one year. Importantly, they focused on transiting planets, whose sizes are directly measured rather than guessed.

Planet properties came from the NASA Exoplanet Archive as of May 22, 2025, then were updated using detailed follow up studies. In total, the researchers assembled eccentricity measurements for 578 planets. After removing systems without reliable age estimates, 537 planets remained for calibrating the tidal model. Circularization times were calculated for an even broader set of 668 planets.

Care was taken to avoid a common pitfall. Some planets are listed as having zero eccentricity simply because their data are too sparse to detect small deviations. The team excluded these assumed cases when building the core calibration, ensuring that the method rested on real measurements.

A typical tidal efficiency, with rare exceptions

After running thousands of statistical tests, the researchers found that a tidal quality factor near 500,000 best matched the observed data. With this value, planets expected to still be evolving showed higher eccentricities, while those expected to be old and settled were mostly circular. The result fits comfortably within estimates for Jupiter and suggests that many hot Jupiters share similar internal behavior.

The study also explored delays before tides begin to act strongly, such as those caused by long term gravitational cycles. Adding a one billion year delay slightly shifted the preferred value but did not change the overall picture.

Most planets behaved as expected, but two stood out. XO 3 b and CoRoT 16 b both appear old enough to have circularized many times over, yet they still follow notably eccentric paths. These rare cases, less than one percent of the sample, may reflect unusual internal structures or systems caught in the act of change.

Identifying quiet movers near their stars

With the tidal clock set, the team turned to planets already on nearly circular orbits. Among these, they highlighted those whose circularization times exceed their system ages. For these worlds, high eccentricity migration cannot work. There has simply not been enough time for tides to do the job.

"You can think of these planets as the “quiet movers,” Kawai explained to The Brighter Side of News. "Their orbits are too neat and too young, in tidal terms, for a violent past to make sense. That makes them prime targets for future missions that want to connect migration history to atmospheric chemistry, such as measuring carbon-to-oxygen ratios. Seventeen of the candidates are already marked as Tier 3 targets for the upcoming Ariel mission," he continued.

Using a standard definition of hot Jupiters, the study identified 13 strong disk migration candidates with well measured eccentricities. When planets with only upper limits are included, the list grows to 36 systems. These planets appear to have arrived quietly, without the chaos expected from strong gravitational kicks.

Several patterns reinforce this view. These candidates tend to have orbits aligned with their stars. Many also retain nearby planetary companions, something high eccentricity migration usually destroys. Statistical tests show that this clustering of companions is unlikely to occur by chance.

The team also reports a possible gap in the masses of these quiet migrants. Planets within a certain mass range appear less likely to survive smooth migration without being driven to the very inner edge of the disk. While intriguing, this hint will require larger samples to confirm.

Looking ahead to deeper clues

The findings point to clear paths for future work. Better age estimates and more precise eccentricity measurements will sharpen the boundary between violent and gentle migration histories. New measurements of orbital tilt for the identified candidates will test whether smooth disk migration truly preserves alignment.

Searching existing data from Kepler and TESS for subtle timing shifts or faint companion transits could also reveal more survivors of migration. Combined with future atmospheric studies, especially with the upcoming Ariel mission, these observations may link how a planet moved inward with where it formed and what it is made of.

Understanding how hot Jupiters reached their tight orbits remains central to the broader story of planetary systems. This new timing based method offers a rare way to rule out one path entirely, rather than infer it indirectly.

Practical Implications of the Research

By identifying hot Jupiters that could not have formed through violent orbital disruptions, the study provides a clearer map of planetary migration pathways. This helps astronomers predict where planets formed within their disks and how common different migration processes are.

In the long term, connecting orbital history with atmospheric composition could reveal how planets acquire water, carbon, and other key elements. These insights deepen our understanding of how planetary systems, including our own, take shape.

Research findings are available online in The Astronomical Journal.

hot Jupiter migration

Related Stories

- Scientists baffled by 'Hot Jupiter' exoplanet's irregular motion

- JWST may have found a thick atmosphere in an unexpected place — an ultra-hot super-Earth

- Exoplanet TRAPPIST-1e may hold Earth-like atmosphere, JWST finds

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.

Joseph Shavit

Writer, Editor-At-Large and Publisher

Joseph Shavit, based in Los Angeles, is a seasoned science journalist, editor and co-founder of The Brighter Side of News, where he transforms complex discoveries into clear, engaging stories for general readers. With vast experience at major media groups like Times Mirror and Tribune, he writes with both authority and curiosity. His writing focuses on space science, planetary science, quantum mechanics, geology. Known for linking breakthroughs to real-world markets, he highlights how research transitions into products and industries that shape daily life.