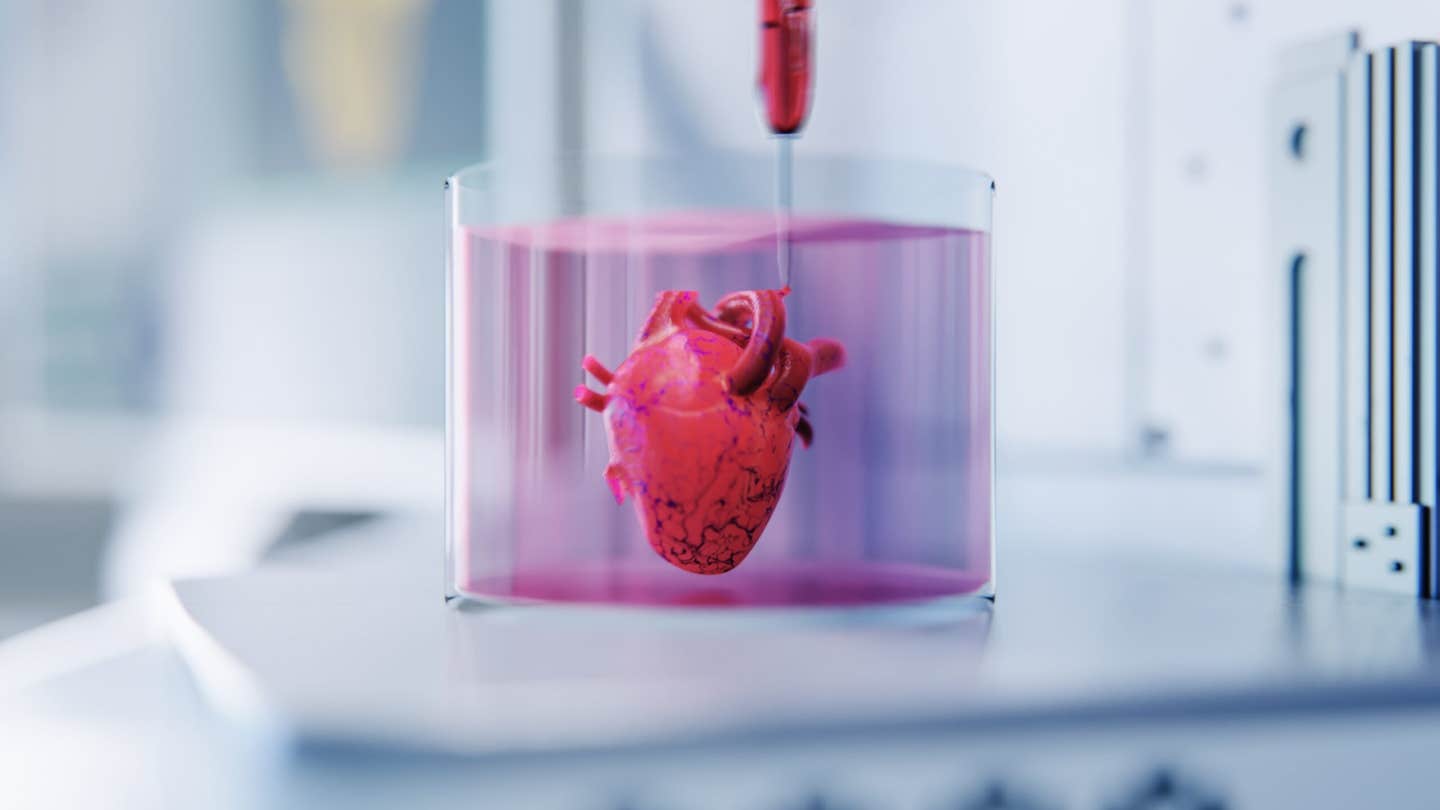

Tiny human heart organoids open the door to safer, faster drug discovery

Scientists have built tiny, beating human heart organoids that can be pushed into an atrial fibrillation state and then brought back toward a normal rhythm with drugs.

Michigan State University scientists have built tiny beating heart organoids that can be driven into atrial fibrillation with inflammation and brought back toward a steady rhythm with drugs. The model finally gives researchers human based tissue to study arrhythmias, speed drug discovery and move toward personalized heart treatments. (CREDIT: Shutterstock)

Millions of people live with atrial fibrillation, a racing, uneven heartbeat that can leave you exhausted and scared. Yet it has been at least 30 years since a new drug for this common rhythm problem reached patients. One major reason is simple and frustrating. Scientists have not had a realistic human heart model to test ideas and medicines.

That gap may finally be closing. Researchers at Michigan State University have built tiny, beating human heart organoids that can be pushed into an atrial fibrillation state and then brought back toward a normal rhythm with drugs. For the first time, you can watch something that looks and behaves like human heart tissue slip into arrhythmia in a dish.

Building a Miniature Human Heart

The work started in 2020, when MSU scientist Aitor Aguirre and his team began growing three dimensional heart organoids from donated human stem cells. These stem cells can turn into many different cell types. With the right signals, they self organize into small, lentil sized structures that pulse on their own.

These mini hearts are not simple clumps of muscle. They form chamber like spaces and a branching network of arteries, veins and capillaries. Their beat is strong enough that you can see it without a microscope. That level of structure lets researchers study heart development, disease and drug responses in ways that flat cell cultures or animal hearts cannot match.

Aguirre, an associate professor of biomedical engineering and head of developmental and stem cell biology at MSU’s Institute for Quantitative Health Science and Engineering, calls them “truly mini hearts.” They behave much more like living human tissue than most previous lab models.

Adding the Heart’s Own Immune Cells

The latest leap came when osteopathic medicine physician scientist student Colin O’Hern added immune cells called macrophages to the organoids. In a developing human heart, these long lived immune cells guide growth, clear debris and help shape healthy tissue. Until now, most lab models left them out.

“Our new model allows us to study living human heart tissue directly, something that hasn’t been possible before,” O’Hern told The Brighter Side of News. "By mixing macrophages into the organoids, our team created a more realistic version of the human heart, one that includes its built in immune system."

Then they did something bold. They triggered inflammation inside the organoids, much like what happens in people with chronic heart stress. When they added inflammatory molecules, the once steady organoids started to misfire.

“When we added inflammatory molecules, the heart cells began beating irregularly,” O’Hern said. “Then we introduced an anti-inflammatory drug, and the rhythm partially normalized. It was incredible to see that happen.”

Recreating Atrial Fibrillation in a Dish

That irregular beating pattern mimics atrial fibrillation, often called A fib. In this condition, the heart’s upper chambers quiver instead of squeezing in a smooth, coordinated way. The result can be palpitations, shortness of breath, blood clots and a higher risk of stroke.

For decades, drug development for A fib has stalled. Existing medicines often treat symptoms, not root causes. Many come with serious side effects. Part of the problem is that animal models do not copy the human disease very well. Hearts in mice, rats or dogs do not respond exactly like human hearts do.

“This new model can replicate a condition that is at the core of many people’s medical problems,” Aguirre said. “It’s going to enable a lot of medical advances so patients can expect to see accelerated therapeutic developments, more drugs moving into the market, safer drugs and cheaper drugs, too, because companies are going to be able to develop more options.”

In the study, the team showed that resident immune cells help guide heart rhythm in early development. Then they pushed the organoids further by “aging” them. They exposed the mini hearts to longer term inflammatory signals until the tissue started to resemble an adult heart facing chronic stress.

From Inflammation to Irregular Rhythm

As inflammation built up, the organoids developed unstable, uneven beats like those seen in A fib. That link between immune activity and arrhythmia came into sharp focus once the researchers added a candidate anti inflammatory drug. Based on the biology they observed, they predicted the drug would calm the rhythm. It did. The treatment restored a more regular beat in the organoids.

Aguirre explained that adding immune cells makes the model more accurate than past systems. “We’re now seeing how the heart’s own immune system contributes to both health and disease,” he said. “This gives us an unprecedented view of how inflammation can drive arrhythmias and how drugs might stop that process.”

The findings also reach beyond rhythm problems. By watching how resident immune cells steer early heart formation, the group gained clues about congenital heart disease, the most common birth defect in humans. If you can see where development goes wrong, you have a better chance of fixing it.

A Platform for Faster, Safer Drug Discovery

The lack of realistic human models has held back new treatments for rhythm disorders. You cannot easily test experimental drugs on living human hearts, and poorly matched animal models often give misleading results. The new organoids offer a middle path.

“Our new human heart organoid model is poised to end this 30 year drought without any new drugs or therapies,” Aguirre said. The technology also supports the National Institutes of Health’s New Approach Methodologies mission, which pushes for human based systems to improve preclinical testing.

MSU teams are now working with pharmaceutical and biotech partners to screen compounds. The goal is twofold. First, they want to find drugs that prevent or treat arrhythmias driven by inflammation. Second, they want to catch compounds that quietly damage heart tissue before they ever reach human trials.

Other contributors from MSU’s Institute for Quantitative Health Science and Engineering, Corewell Health and Washington University helped refine imaging, engineering and clinical links for the project. The work is supported by multiple groups, including the National Institutes of Health, National Science Foundation, Corewell Health partners, the Saving tiny Hearts Society and the American Heart Association.

Aguirre’s group has published several studies on human heart organoids, placing Michigan State among the leaders in this field. He already has his eye on the next horizon. “Our longer term vision is to develop personalized heart models derived from patient cells for precision medicine and to generate transplant ready heart tissues one day,” he said.

For people living with atrial fibrillation, that future could mean something very concrete. New drugs that treat the real drivers of arrhythmia, not just the symptoms, and treatments that are safer, more precise and easier to tailor to your unique heart.

Practical Implications of the Research

This work gives scientists a living human platform to probe atrial fibrillation at its roots, rather than guessing from animal models or indirect measurements. Researchers can watch how inflammation flips a healthy rhythm into chaos and then test drugs that either block or reverse that shift. That should speed the path toward new A fib treatments after a 30 year dry spell.

Because the organoids are grown from human stem cells, future versions can be made from a patient’s own cells. This could let doctors test drugs on your personal mini heart before prescribing them, cutting the risk of dangerous side effects. The same system can screen hundreds of compounds to ensure they do not quietly harm the heart, helping regulators and companies bring safer medicines to market.

Beyond arrhythmias, the model can reveal how immune cells shape early heart development and how congenital defects arise. That knowledge may guide new prenatal or early life interventions. Over time, the organoid platform could expand toward building larger, more complex heart tissues suitable for repairing damaged muscle or even for transplant.

Research findings are available online in the journal Cell Stem Cell.

Related Stories

- Smartwatch heart signals may offer an accurate and safe way to verify age online

- Origami 3D printed belt uses AI to spot dangerous heart rhythms in real time

- Experimental RNA drug helps hearts heal after heart attacks

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.

Hannah Shavit-Weiner

Medical & Health Writer

Hannah Shavit-Weiner is a Los Angeles–based medical and health journalist for The Brighter Side of News, an online publication focused on uplifting, transformative stories from around the globe. Passionate about spotlighting groundbreaking discoveries and innovations, Hannah covers a broad spectrum of topics—from medical breakthroughs and health information to animal science. With a talent for making complex science clear and compelling, she connects readers to the advancements shaping a brighter, more hopeful future.