USC scientists develop safer, more accurate Alzheimer’s detection method

Alzheimer’s disease affects more than seven million Americans, slowly erasing memory and thinking skills.

Scientists developed a simple, noninvasive brain test that outperforms costly scans and painful spinal taps in detecting Alzheimer’s early. (CREDIT: Shutterstock)

Alzheimer’s disease affects more than seven million Americans, slowly erasing memory and thinking skills. For decades, doctors have relied on painful spinal taps, expensive brain scans, and imperfect behavioral tests to diagnose it. These methods often focus on detecting amyloid plaques and tau tangles—proteins that build up in the brain and damage nerve cells. While useful, these tools are far from perfect and often catch the disease after it has already taken hold.

A team of biomedical engineers at the University of Southern California’s Viterbi School of Engineering is challenging this long-standing approach. Led by Vasilis Marmarelis, Dean’s Professor in the Alfred E. Mann Department of Biomedical Engineering, the researchers developed a new, noninvasive way to measure brain health. Instead of tracking sticky proteins, they looked at how the brain regulates blood flow and oxygen. Their method, called the Cerebrovascular Dynamics Index, or CDI, could revolutionize how Alzheimer’s is detected and treated.

Looking at the Brain’s “Plumbing”

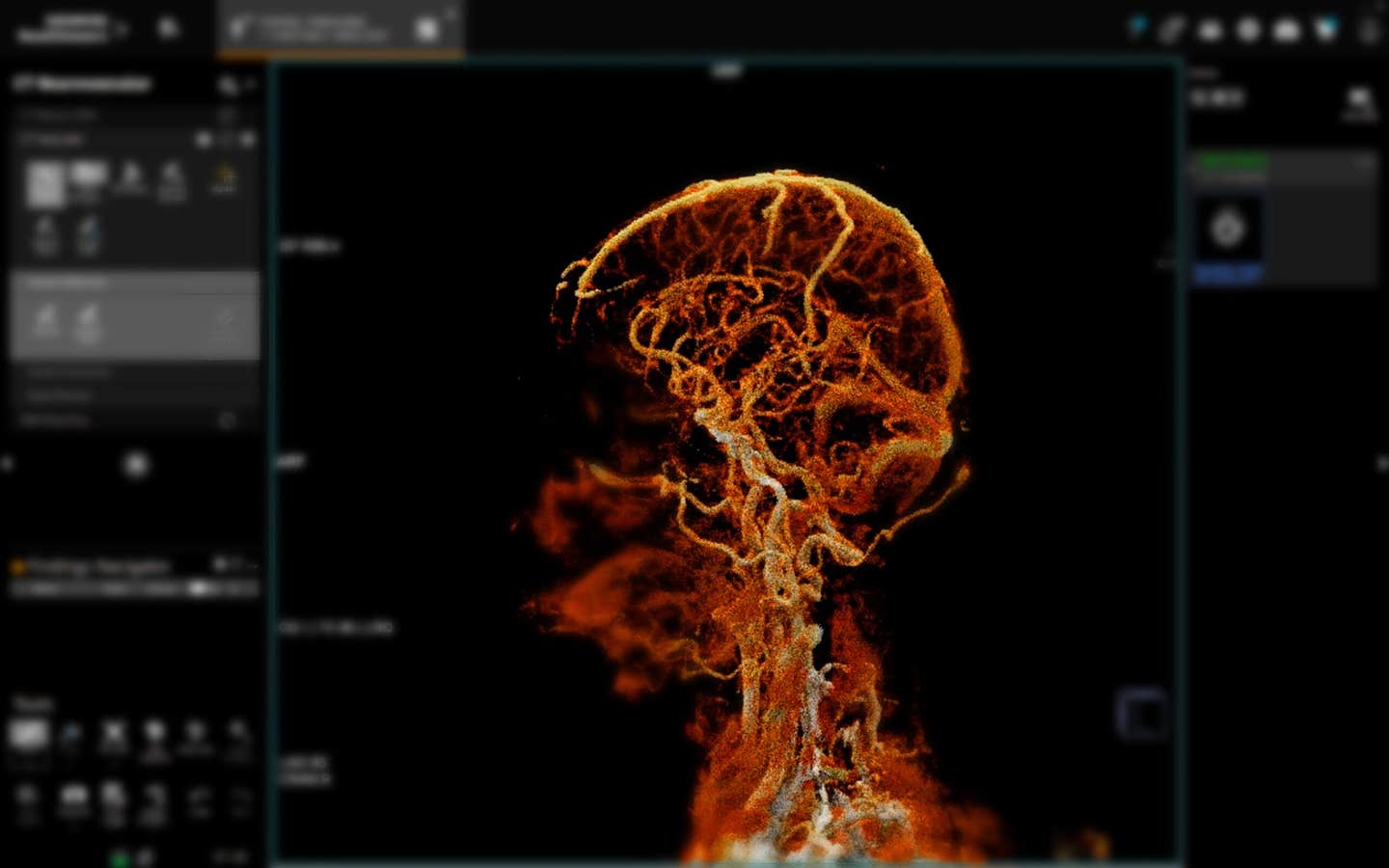

Think of your brain like a city. To keep it running, it needs a steady supply of oxygen and nutrients delivered through a network of blood vessels. When you concentrate, blood vessels expand to carry away extra carbon dioxide and deliver more oxygen. This process, known as vasomotor reactivity, is like traffic lights adjusting to rush-hour demand.

Marmarelis noticed something unusual nearly 15 years ago: people with Alzheimer’s often have trouble widening these vessels when needed. That means their brains can’t get oxygen, glucose, and nutrients quickly enough. “They cannot dilate the cerebral vessels to bring more blood in and provide adequate blood perfusion to the brain,” Marmarelis explained. “This means they don’t get the oxygen, nutrients and glucose that we need for cognition in a timely manner.”

His team decided to investigate whether this breakdown in blood vessel function could be measured and used as an early warning sign.

How the CDI Works

The CDI test is simple and painless. It combines Doppler ultrasound, which tracks blood moving through brain arteries, with near-infrared spectroscopy, which measures oxygen levels in the brain’s cortex. Together, these tools capture how quickly blood vessels react to changes in blood pressure and carbon dioxide.

Unlike spinal taps or PET scans that involve radioactive tracers, the CDI is noninvasive and quick. No needles, no injections—just a combination of ultrasound and light to reveal how well your brain adjusts to shifting demands.

Related Stories

- Groundbreaking test can reveal Alzheimer’s risk years before diagnosis

- Omega-3’s could protect women from Alzheimer’s disease

This approach shifts focus away from proteins like amyloid and tau and instead spotlights the “plumbing system” that keeps the brain alive and healthy.

Testing the CDI

The study, funded by the National Institutes of Health, tested nearly 200 people across multiple centers. Participants included healthy volunteers, those with mild cognitive impairment (MCI), and people in the early stages of Alzheimer’s.

When compared to standard diagnostic tools, the CDI outperformed them all. Using a common measure called the Area Under the Curve (AUC), which rates test accuracy from 0.5 (random guess) to 1.0 (perfect score), the CDI scored an impressive 0.96. For comparison, amyloid PET scans reached 0.78, while common cognitive assessments such as the MoCA and MMSE scored around 0.91 to 0.92.

The CDI was especially powerful in telling apart people with mild cognitive impairment from those already experiencing Alzheimer’s, scoring 0.98—remarkably close to perfect. In contrast, amyloid PET struggled at this stage.

Beyond the AUC, the CDI showed clear advantages in other ways. Its sensitivity—the ability to correctly identify people with the disease—was about 87 percent. Its specificity—the ability to rule out false alarms—was 93 percent. That’s stronger than amyloid PET, which had just 67 percent sensitivity.

The CDI also excelled at predicting outcomes. When it identified someone as having Alzheimer’s, it was correct 93 percent of the time. When it cleared someone as not having the disease, it was right 87 percent of the time. For patients and doctors, those numbers can make all the difference.

A Challenge to Old Thinking

For years, the “amyloid cascade hypothesis” has guided research and treatment. It argues that amyloid buildup triggers tau tangles, leading to cell death and cognitive decline. But Marmarelis believes the story is more complicated.

“What we have that others didn’t have before is a methodology to quantify these dynamic relations that’s extremely robust and accurate,” he said. “This indicates that the particular aspect of dysregulation of cerebral perfusion regulation may be the critical aspect in the pathogenesis of this disease, probably in conjunction with other factors, including amyloid accumulation.”

In other words, problems with blood flow may be just as important as protein buildup. By focusing only on amyloid and tau, medicine may have overlooked a key piece of the puzzle.

What Comes Next

The promise of the CDI lies not just in better diagnosis but also in shaping new treatments. If Alzheimer’s is tied to blood flow problems, then therapies aimed at restoring healthy circulation could slow or even prevent decline.

The team highlighted several possibilities:

- Aerobic exercise: Regular walking, biking, or swimming could improve vessel response. Even 20–30 minutes a day may help.

- The MIND diet: Rich in leafy greens, berries, nuts, whole grains, olive oil, and fish, this diet supports healthy circulation and reduces harmful fats and sugars.

- Breathing techniques: Controlled exposure to mild low-oxygen or high-carbon dioxide environments might “train” vessels to respond more effectively.

- Vagus nerve stimulation: A noninvasive device that stimulates the nerve through the ear shows early promise for boosting blood flow regulation.

These ideas are still in testing, but they open a new chapter in the fight against Alzheimer’s.

Practical Implications of the Research

This study suggests that doctors could soon diagnose Alzheimer’s earlier, faster, and with greater accuracy using a simple, noninvasive test. By focusing on blood flow dynamics instead of invasive or expensive protein scans, care could become more accessible in regular clinics—not just elite research hospitals.

The CDI may also inspire new treatments built around improving circulation and oxygen delivery in the brain. That means lifestyle strategies like exercise and healthy eating could become central parts of care, alongside emerging technologies such as nerve stimulation.

If future research confirms its accuracy, the CDI could reshape how doctors understand and treat Alzheimer’s, offering hope for millions of families facing this devastating disease.

Research findings are available online in the journal Alzheimer s & Dementia Diagnosis Assessment & Disease Monitoring.

Note: The article above provided above by The Brighter Side of News.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.