World-first room-temperature RTD looks to safely deliver terahertz wireless communication

Nagoya University builds a room-temperature RTD using Group IV materials, a key step toward scalable terahertz wireless components.

Edited By: Joseph Shavit

Edited By: Joseph Shavit

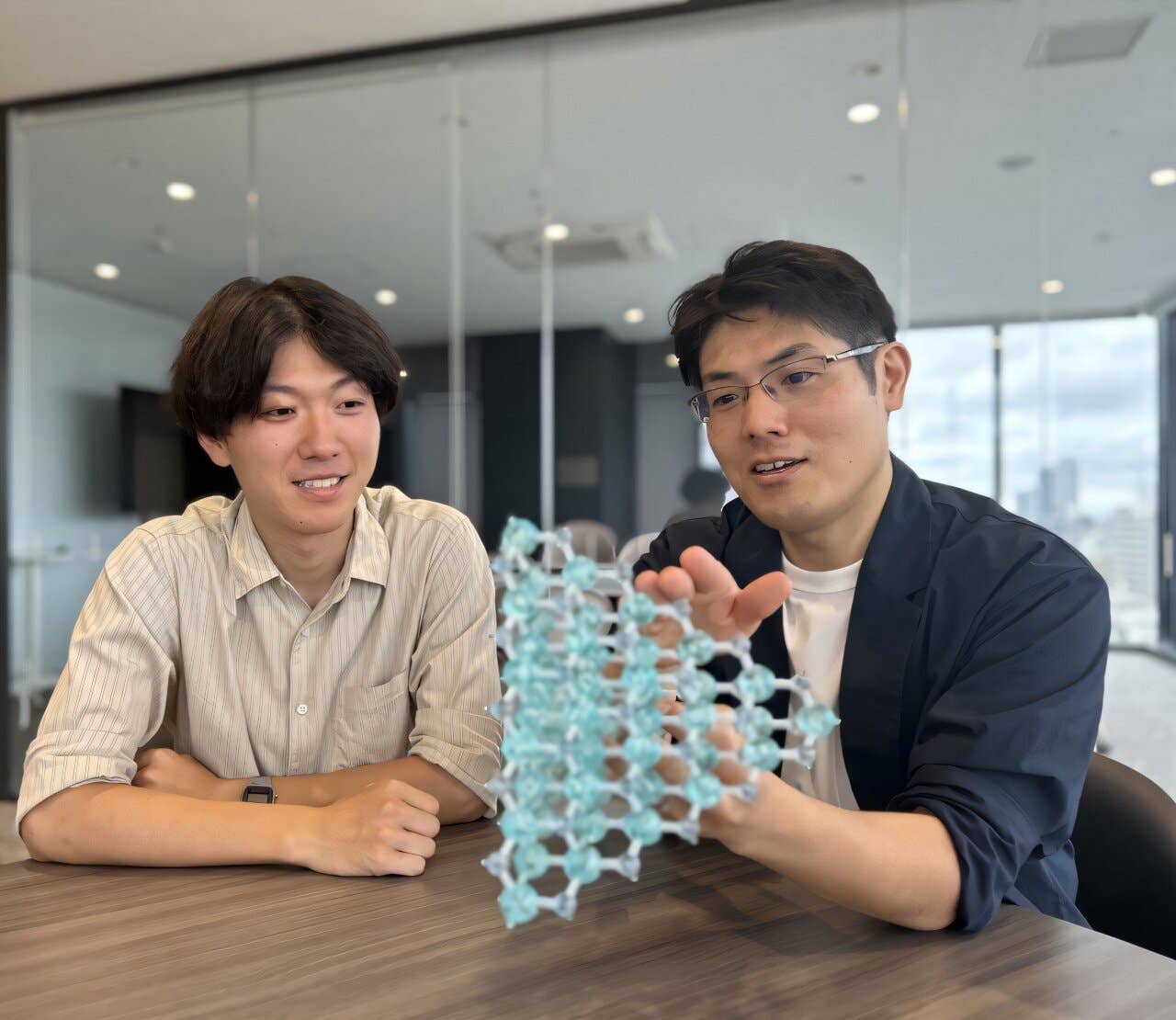

Assistant Professor Shigehisa Shibayama (right) and lead author Shota Torimoto (left), together with their colleagues, created a room-temperature resonant tunneling diode made entirely from non-toxic Group IV semiconductor materials. (CREDIT: Shigehisa Shibayama (Nagoya University) and Shota Torimoto (Nagoya University))

Terahertz wireless has long sounded like the next big leap; fast enough to move huge amounts of data with less delay. Yet the hardware has struggled to keep up. A key part, the resonant tunnel diode, has often demanded extreme cooling or relied on materials that raise cost and safety concerns.

Now researchers at Nagoya University in Japan say they have cleared a major hurdle. In what they describe as a world first, the team developed a resonant tunnel diode that runs at room temperature and uses only Group IV semiconductor materials. That means it avoids toxic and rare elements used in many earlier designs.

The achievement matters because a room-temperature device can leave the lab and enter real systems. It also fits better with sustainable manufacturing goals. The team says the new diode could help unlock terahertz components for next-generation wireless communication systems.

A Tiny Device With a Big Job

A resonant tunnel diode, often called an RTD, is a quantum device built from layers so thin they span only a few atoms. Its key feature is negative differential resistance, where current can drop as voltage rises. That behavior can sound backward, but it proves useful.

In the right circuit, negative differential resistance lets the diode sustain very high-frequency oscillations. Those oscillations can support terahertz signals, which vibrate about a trillion times per second. Researchers see terahertz links as one promising path toward the high speed and heavy data loads expected from sixth-generation, or 6G, networks.

Scientists have pursued RTDs for years, but many devices have depended on Group III-V materials such as InGaAs. Those approaches can involve indium and arsenic, which bring toxicity and supply concerns. They can also complicate large-scale manufacturing.

“Compared to InGaAs-based Group III-V RTDs that include toxic and rare elements, such as indium and arsenic, Group IV compounds-based RTDs are safer, lower cost, and offer advantages for creating integrated production processes,” said senior author Dr. Shigehisa Shibayama of the Nagoya University Graduate School of Engineering to The Brighter Side of News.

Why Room Temperature Changes Everything

Earlier work by the same research group pointed toward a safer path. The team created a p-type RTD using Group IV materials, specifically germanium-tin (GeSn) and germanium-silicon-tin (GeSiSn) alloys. Yet the device only worked at extremely low temperatures, around minus 263 degrees Celsius.

That level of cooling keeps a device locked in research settings. Consumer electronics and network hardware cannot depend on such cold conditions. Even many advanced lab systems would struggle to scale that approach.

In the new study, the team reports a p-type RTD that functions around room temperature, about 27 degrees Celsius. That shift moves the device from “interesting physics” toward “usable component.” It also raises the odds that terahertz circuits could one day reach broader deployment.

The team’s goal was not just to prove tunneling works in Group IV materials. They aimed to protect the delicate layer structure that makes the tunneling “resonant,” meaning selective and efficient.

The Barrier Layers That Must Stay Clean

An RTD depends on a double-barrier structure. In simple terms, electrons or holes tunnel through two thin barrier layers with a well-like region between them. If the layers stay crisp and separate, the diode can produce negative differential resistance.

If the layers mix, the effect can collapse. If defects form, current can leak through easier routes. That leakage can overwhelm the special tunneling behavior and ruin the device’s performance.

“The RTD cannot function if these layers are mixed,” Shibayama said. “If there are defects in the layers, electrons can tunnel through these easier routes, leading to current leakage. This leakage current needs to be reduced for negative differential resistance; the key property of an RTD; to occur.”

That problem has shaped the field for years. Building layers a few atoms thick sounds clean in theory, but real growth can create rough surfaces, island-like structures, and unwanted blending between layers.

A Simple Gas With a Crucial Role

The team’s breakthrough came from a change during layer formation. They introduced hydrogen gas and tested three different approaches.

First, they introduced hydrogen gas to both the two GeSiSn layers and the three GeSn layers. Second, they used no hydrogen gas. Third, they introduced hydrogen gas only to the three GeSn layers.

The last scenario worked best. Hydrogen gas restricted island growth and limited mixing between layers. That produced a smoother, more ordered double-barrier structure. With cleaner barriers, the diode could show the negative differential resistance needed for high-frequency operation.

This finding also offers a practical lesson for device engineering. You can think of hydrogen as helping the material “settle” into the right shape, instead of clumping and blending. The diode’s success depends on those microscopic details.

The researchers frame the result as a step toward terahertz wireless components that combine speed, data handling, and energy efficiency. They also emphasize the manufacturing upside of Group IV materials, since those elements fit more naturally into established semiconductor workflows.

Practical Implications of the Research

If engineers can build terahertz systems that work at room temperature, you could see real changes in how wireless devices move data. Faster links could support higher-capacity networks in dense environments, where today’s systems strain under video, sensors, and constant connectivity. The work also points toward better energy efficiency, since a device that sustains high-frequency signals without extreme cooling can avoid major power costs.

The materials angle matters too. By avoiding toxic and rare elements, Group IV RTDs could reduce supply risks and improve safety in manufacturing. That shift could make it easier to scale production and integrate these diodes into broader chipmaking processes.

For researchers, the study also highlights a concrete method, hydrogen introduced during specific layer growth, to reduce defects and improve barrier quality. That technique could guide future experiments and speed the path from prototypes to practical circuits.

Still, the study does not claim consumer-ready hardware today. It offers a key building block and a clearer recipe for making it work under everyday conditions. The next progress will come from refining performance and integrating these diodes into complete terahertz components.

Research findings are available online in the journal ACS Applied Electronic Materials.

Related Stories

- Wireless implant sends information straight to the brain using light

- Next-gen wireless chip boosts battery life and reduces signal errors

- Ultrasound technology brings wireless power to medical implants

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.

Joshua Shavit

Writer and Editor

Joshua Shavit is a NorCal-based science and technology writer with a passion for exploring the breakthroughs shaping the future. As a co-founder of The Brighter Side of News, he focuses on positive and transformative advancements in technology, physics, engineering, robotics, and astronomy. Joshua's work highlights the innovators behind the ideas, bringing readers closer to the people driving progress.