Mount Vesuvius’s 79 A.D. eruption was far more devastating than imagined

As Vesuvius erupted, the city was buried in pumice for nearly 18 hours. Residents who stayed thought the worst had passed. They were wrong.

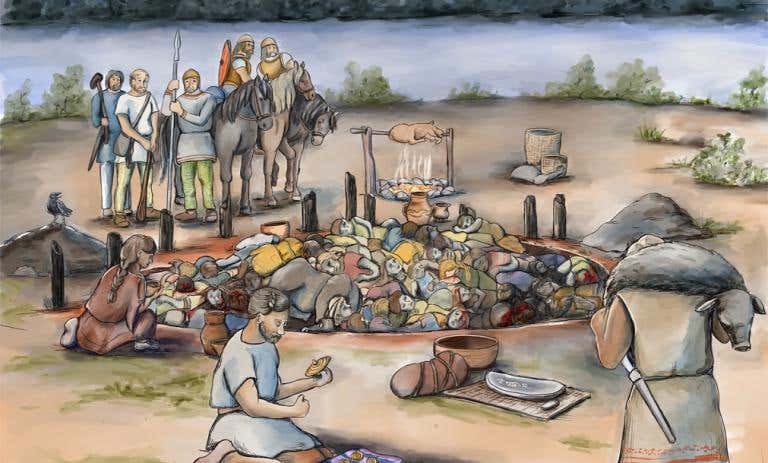

Nearly 2,000 years ago, Pliny the Younger described the ground shaking as Mount Vesuvius exploded in fury. (CREDIT: AI Generated, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Nearly 2,000 years ago, Pliny the Younger described the ground shaking as Mount Vesuvius exploded in fury. That eruption devastated Pompeii. Now, new research is digging deeper into what really happened beneath the ash.

Scientists from Italy’s Istituto Nazionale di Geofisica e Vulcanologia (INGV) and the Pompeii Archaeological Park are leading this investigation. Their work uncovers how earthquakes and volcanic eruptions acted together—rather than separately—to bring the ancient city to ruin.

Most studies focus on eruptions alone. But this team, publishing in Frontiers in Earth Science, took a new approach. “These complexities are like a jigsaw puzzle,” said volcanologist Dr. Domenico Sparice. “All the pieces must fit together to unravel the complete picture.”

Sparice believes the earthquakes did more than shake the earth. He says they shaped how people reacted, possibly altering decisions during those terrifying hours. The ground didn’t just rumble—it forced action.

Understanding this link is key, said Dr. Fabrizio Galadini, a senior researcher on the project. Without it, we miss how damage unfolds. “It is essential for reconstructing the interplay between volcanic and seismic events,” he explained.

Excavations at the “Casa dei Pittori al Lavoro” brought surprises. Walls had collapsed in strange ways—patterns not seen in known volcanic effects. “There had to be a different explanation,” said Dr. Mauro Di Vito, who leads the Vesuvian observatory. Then came the chilling discovery: two skeletons, crushed and fractured.

As Vesuvius erupted, the city was buried in pumice for nearly 18 hours. Residents who stayed thought the worst had passed. They were wrong. Powerful earthquakes hit next. Weakened roofs and walls gave way under the weight.

“The people who did not flee their shelters were possibly overwhelmed by earthquake-induced collapses,” said anthropologist Dr. Valeria Amoretti. “This was the fate of the two individuals we recovered.”

Related Stories

The researchers found two male skeletons, both around 50 years old. Their positioning suggested that ‘individual 1’ was crushed by a large wall fragment, leading to immediate death. ‘Individual 2’ appeared to have tried to protect himself with a round wooden object, traces of which were found in the volcanic deposits.

Several clues indicate these individuals did not die from inhaling ash or extreme heat. Their positions on top of the pumice lapilli, rather than beneath it, suggest they survived the first phase of the eruption. They were likely overwhelmed by collapsing walls during the temporary decline of the eruptive phenomena, before the arrival of the deadly pyroclastic currents.

While not everyone could reach temporary safety, the presence of many victims in the ash deposits suggests that some tried to flee. However, reliable estimates of how many people died due to volcanic or earthquake-related causes are unavailable.

“New insight into the destruction of Pompeii gets us very close to the experience of the people who lived here 2,000 years ago. The choices they made, as well as the dynamics of the events, remain a focus of our research and decided over life and death in the last hours of the city’s existence,” concluded Dr. Gabriel Zuchtriegel, director of Pompeii Archaeological Park.

10 facts you may not know about Mt. Vesuvius

Mount Vesuvius is made up of two volcanoes: Mount Vesuvius is not just one volcano. The main peak is called Vesuvius, but it is attached to another mountain, Monte Somma. Monte Somma has a crater at the top, which was created by a past eruption. Mount Vesuvius actually grew from the top of Monte Somma.

People of Pompeii didn't know they lived near a volcano: Before the massive eruption in 79 AD, the people of Pompeii didn't know they were living next to a volcano because it hadn't erupted for about 1,800 years. Since then, it has been very active, erupting six times in the 18th century, eight times in the 19th century, and three times in the 20th century. Its last eruption was in 1944.

There was no word for volcano before 79 AD: After the eruption in 79 AD, the word "volcano" was created, named after Vulcan, the Roman god of fire and metalworking.

The volcano gave warning signs before the eruption in 79 AD: Before the eruption, there were several earthquakes. The people of Pompeii and Herculaneum didn't realize these were warning signs. In 62 AD, a big earthquake destroyed many buildings. Some people moved away from the area because of this, which turned out to be a lucky escape.

It rained elephants… well, not really: When the volcano erupted almost 2,000 years ago, it blasted tons of volcanic debris into the air. This debris fell like rain on the surrounding towns. To give you an idea of how much debris fell, it was like 250,000 elephants falling per second!

The eruption ended in 24 hours: Around midday on August 24th in the year 79, Mount Vesuvius began to erupt. First, it blasted pumice stones high into the air. These stones fell like rain for about five hours, burying the towns. The stones grew larger over time, causing buildings to collapse. Seventeen hours later, a fierce flow of hot gas and debris rushed out of the volcano, covering Pompeii and Herculaneum in minutes. After a day of continuous eruption, the volcanic dust finally began to settle.

Pompeii was perfectly preserved until recently: For over 1,600 years, Pompeii remained well-preserved until it was discovered in the 18th century. However, human activity and natural weathering have since caused damage. Archaeologists are worried about preserving the site.

The World Monuments Fund, an organization dedicated to protecting historic architecture, recognizes Pompeii. It will cost an estimated $335 million to conserve the site. Although much of Pompeii and nearby Herculaneum are still buried, it is uncertain how long the uncovered artifacts will last.

We haven't uncovered everything that Mount Vesuvius buried: Only about two-thirds of Pompeii and even less of Herculaneum have been excavated. Many parts of these ancient cities remain buried to protect them. Herculaneum is now under the city of Ercolano. While parts of Ercolano have been demolished to allow excavations, it's unlikely the rest will be uncovered soon. There might still be many treasures and secrets waiting to be found!

Mount Vesuvius makes the land fertile: Many people live near Mount Vesuvius because the volcanic soil is great for growing plants. The ash and lava from the volcano are rich in minerals like potassium, phosphorus, and nitrogen, making the soil very fertile.

In the town of Irpinia near Mount Vesuvius, they grow red grapes (Aglianico) and white grapes (Fiano and Greco di Tufo), which make delicious wines. The area also grows a special type of tomato, ‘Pomodorino del Piennolo del Vesuvio,’ known for its quality.

The hardened lava acts like a sponge, storing water in the ground. Because of this, many vineyards around Mount Vesuvius don't need artificial irrigation during summer, as the soil slowly releases water to the plants.

Mount Vesuvius is still active and will erupt again: Mount Vesuvius is one of the most dangerous volcanoes in the world. Scientists believe another eruption is overdue and will be very powerful. The magma beneath Vesuvius covers 154 square miles – that's a lot of magma.

When it erupts, it could affect over 3 million people and destroy the city of Naples. This sounds scary, but scientists monitor the volcano 24/7, so there will be enough time to warn people and move them to safety.

Note: The article above provided above by The Brighter Side of News.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.