12,000-year-old brains provide new insight into Alzheimer’s, study finds

Researchers have challenged previous notions regarding the rarity of brain preservation in the archaeological record.

Researchers have challenged previous notions regarding the rarity of brain preservation in the archaeological record. (CREDIT: Graham Poulter)

A recent study by researchers at the University of Oxford has challenged previous notions regarding the rarity of brain preservation in the archaeological record. The team conducted an extensive examination of global archaeological literature to compile a database exceeding 20 times the number of brains previously documented. Their findings were published in the Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

Preservation of soft tissue in the geological record is uncommon, and the survival of entire organs, except under specific conditions like embalming or freezing, is particularly unusual.

Historically, the spontaneous preservation of brains amidst skeletonized remains has been viewed as a unique phenomenon. However, this new research reveals that nervous tissues persist more abundantly than traditionally thought, aided by conditions that inhibit decay.

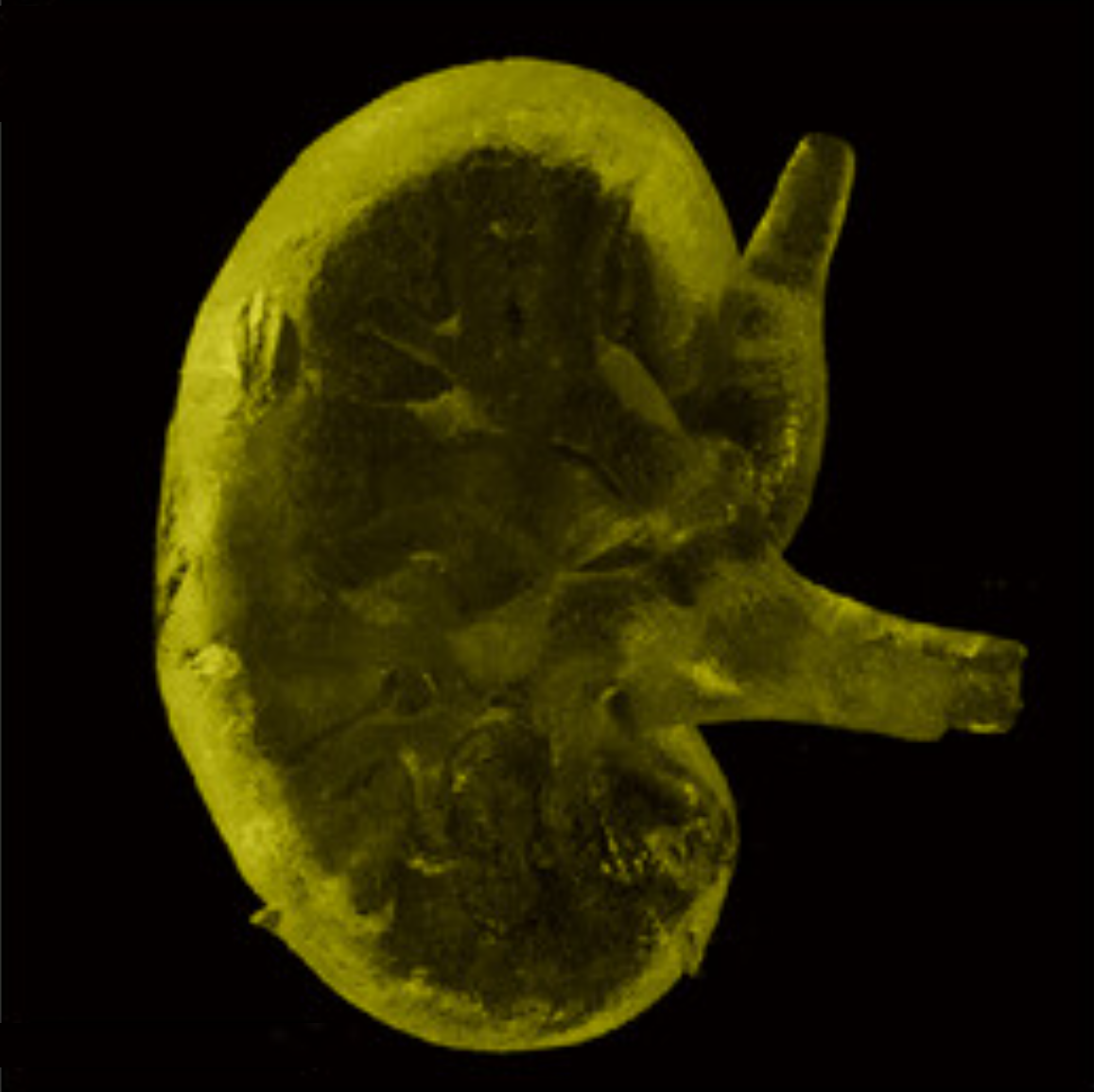

Alexandra Morton-Hayward holding the preserved hemispheres of a 200-year-old brain. (CREDIT: Graham Poulter)

Led by postgraduate researcher Alexandra Morton-Hayward from the Department of Earth Sciences at Oxford, the study compiled records of over 4,000 preserved human brains from more than 200 sources across six continents, excluding Antarctica.

These brains, some dating back 12,000 years, were discovered in records dating to the mid-17th century. They were found in diverse individuals, including Egyptian and Korean royalty, British and Danish monks, Arctic explorers, and war victims.

Through a thorough review of literature and collaboration with historians worldwide, the study uncovered a variety of archaeological sites yielding ancient human brains, such as a Stone Age site in Sweden, an Iranian salt mine from around 500 BC, and Andean volcanoes during the Incan Empire.

Related Stories

Each brain in the database was paired with historic climate data from the corresponding area to examine trends in preservation conditions over time, including dehydration, freezing, saponification, and tanning.

Co-author Professor Erin Saupe from the Department of Earth Sciences at the University of Oxford remarked, "This record of ancient brains highlights the array of environments in which they can be preserved, from the high arctic to arid deserts."

Over 1,300 of the preserved human brains were the only soft tissues found, raising questions about why the brain may endure while other organs decay. Remarkably, these brains are also the oldest in the archive, with some dating back to the last Ice Age. The exact preservation mechanism for these ancient brains remains unknown, although the research team suggests possibilities such as molecular crosslinking and metal complexation.

Fragments of brain from an individual buried in a Victorian workhouse cemetery (Bristol, UK), some 200 years ago. No other soft tissue survived amongst the bones, which were dredged from the heavily waterlogged grave. (CREDIT: Alexandra L. Morton-Hayward)

These ancient brains offer unique insights into the early evolution of our species, including the roles of ancient diseases. Lead author Alexandra Morton-Hayward stated, "In the forensic field, it is well-known that the brain is one of the first organs to decompose after death - yet this huge archive clearly demonstrates that there are certain circumstances in which it survives."

She added, "Whether those circumstances are environmental or related to the brain’s unique biochemistry is the focus of our ongoing and future work. We’re finding amazing numbers and types of ancient biomolecules preserved in these archaeological brains, and it’s exciting to explore all that they can tell us about life and death in our ancestors."

Distribution and frequency of preserved human brains by type, compared with soft tissues in the IsoArcH repository. (CREDIT: Proceedings of the Royal Society B)

The discovery of preserved soft tissues is highly valuable to bioarchaeologists, as they provide a wealth of information beyond what can be gleaned from bones alone.

However, less than 1% of preserved brains have been examined for ancient biomolecules. The untapped archive of 4,400 human brains described in this study offers promising avenues for new insights into ancient health, disease, and the evolution of human cognition and behavior.

For more science news stories check out our New Innovations section at The Brighter Side of News.

Note: Materials provided above by The Brighter Side of News. Content may be edited for style and length.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get the Brighter Side of News' newsletter.