3000-year-old copper smelting site reveals the dawn of iron age technology

New research shows Georgia’s Kvemo Bolnisi site was a copper workshop, not an iron factory, reshaping ideas about early metallurgy.

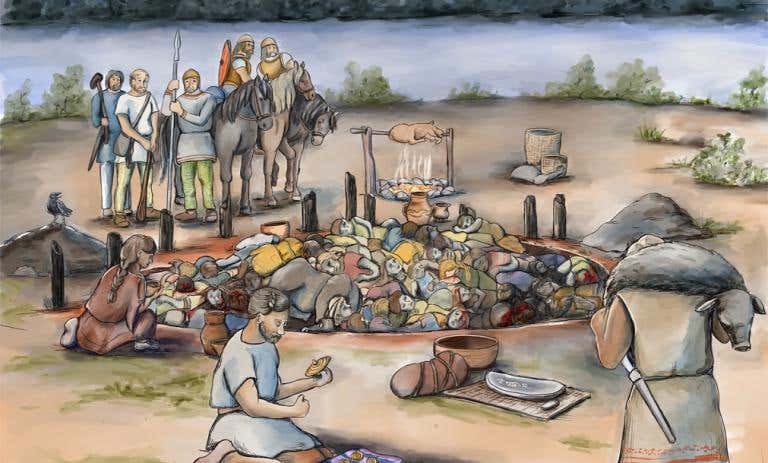

The site, shown here, was originally excavated during the Soviet period and was relocated using hand draw maps from a 1964 book. (CREDIT: Dr Nathaniel Erb-Satullo)

Buried deep in the south Georgia rolling hills, a tiny archaeological site has been rewriting history. Uncovered in the late 1950s, the Kvemo Bolnisi workshop was considered to be one of the Caucasus's oldest iron smelting factories.

Early reports described the picture of a stone furnace into a hillside fit, piles of hematite lying around the floor, and an enormous slag pile out back. Those conclusions convinced archaeologists that local craftsmen were experimenting with iron production between 13th and 7th centuries BC.

For decades, that account shaped what scholars thought about the history of ironworking in the region. But now there's an entirely different tale. A new look at the evidence shows that Kvemo Bolnisi wasn't producing iron at all—it was a copper shop that used iron minerals in unexpected and creative ways.

A Misunderstood Furnace

The perplexity traces its roots to equipment available in the 1950s. Without the use of microscopes and chemical testing available today, archaeologists were stuck with what they could observe by eye. Because the floor of the workshop was smeared with hematite, an iron oxide, the site was labeled an early iron factory. Later studies confirmed the claim, and the label stuck.

That impression began to fall apart when scientists Bobbi Klymchuk and Nathaniel Erb-Satullo, from Cranfield University, returned with new methods. By studying slag, ore, and tiny metal droplets trapped inside the waste product, they found overwhelming evidence of copper, not iron. A few samples were more than 99 percent pure copper. Tiny fragments of malachite, a green-colored copper mineral, added to the evidence.

What seemed to be the region's first iron furnace turned out to be something quite different—a technologically advanced copper-smelting plant.

Copper at the Center of Community Life

The location of the furnace gives yet another suggestion of intrigue. As opposed to western Georgian copper workshops, which were secluded in mountain valleys, Kvemo Bolnisi was located right next to homes and tombs. Metalworking wasn't isolated and specialized. It was a part of everybody's daily routine.

"There is this unusual co-location of settlement, smelting, and mining that is in sharp contrast to other patterns in the region," the scientists stated. The layout implies a closed-system system in which the production of metal was geared toward local ends and not extensive trade networks. To people, copper was not just material for ornaments and instruments—it was integral to subsistence and identity.

The greatest shock was when the team realized the reason why so much hematite had been conserved in the workshop. Rather than being the raw ore for smelting iron, the mineral was being used as a flux. The addition of iron oxide to the furnace changed the slag chemistry so that it was more slippery and easier to take off molten copper.

This small trick improved efficiency and allowed the metalworkers to extract more copper per batch of ore. Some of the droplets of copper pinned in the slag were even nearly pure, showing just how good the technique was. It is now one of the earliest known examples of intentional fluxing in the Caucasus.

Rethinking the Origins of Iron

For centuries, experts argued whether iron ore's chance discovery in furnaces produced the origin of iron smelting. The Kvemo Bolnisi tale provides a different explanation. Copper smelters were testing iron-containing minerals not to produce iron but to improve their copper smelting. Those tests perhaps were an indirect lead to subsequent iron technology.

"Iron is the world's industrial metal par excellence," said Dr. Erb-Satullo. "And that's why this site at Kvemo Bolnisi is so exciting. It's evidence of intentional use of iron in copper smelting. These metalworkers identified iron oxide as a substance and experimented with its properties."

The record shows that the transition from bronze to iron was not a sudden breakthrough. Instead, it was a step-by-step attempt based on centuries of trial, error, and inquiry. By focusing on copper, the metallurgists inadvertently developed the chemical information that eventually made ironworking possible.

A Small Workshop with Big Lessons

Unlike the hundreds of sites of copper smelting found in western Georgia, Kvemo Bolnisi is unique in the east. That relatively small size implies a home-based industry. It wasn't so much about mass production or huge trade networks but local ingenuity, expertise, and survival.

It also illustrates how returning to ancient sites with modern technology can reverse long-held presuppositions. What was thought to be Georgia's earliest iron factory turns out to be a copper workshop using advanced techniques. The heaps of hematite, rather than being misplaced, show an thoughtful solution to metallurgical issues.

As Erb-Satullo described, "There's a beautiful symmetry in this kind of research, in that we can use the techniques of modern geology and materials science to get into the minds of ancient materials scientists. And we can do all this through the analysis of slag—a mundane waste material that looks like lumps of funny-looking rock."

Practical Implications of the Research

The reinterpretation of Kvemo Bolnisi adds depth to our knowledge of technological change. It shows that innovation can build upon efforts to extend existing processes rather than innovations in a giant leap. It's a reminder to archaeologists that long-held assumptions can entirely change with the introduction of new evidence.

To scientists and engineers today, the research demonstrates how problem-solving and creativity shaped even the earliest technology.

By observing how early metallurgists combined observation and experiment, contemporary scientists learn about the origin of scientific thinking itself.

Research findings are available online in the Journal of Archaeological Science.

Related Stories

- Scientists develop an environmentally-friendly method for making steel using electricity

- Ancient Bronze Age material looks to accelerate use of renewable energy in factories

- Breakthrough innovation converts e-waste into valuable rare earth metals

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.

Rebecca Shavit

Writer

Based in Los Angeles, Rebecca Shavit is a dedicated science and technology journalist who writes for The Brighter Side of News, an online publication committed to highlighting positive and transformative stories from around the world. Her reporting spans a wide range of topics, from cutting-edge medical breakthroughs to historical discoveries and innovations. With a keen ability to translate complex concepts into engaging and accessible stories, she makes science and innovation relatable to a broad audience.