Ancient Bolivian temple discovery reveals secrets of lost Tiwanaku society

Newly discovered temple shows Tiwanaku’s trade-based expansion and regional control in Bolivia’s highlands 1,300 years ago.

Graphical representation of what the Palaspata temple may have looked like 1.300 years ago. (CREDIT: CC BY-SA 4.0)

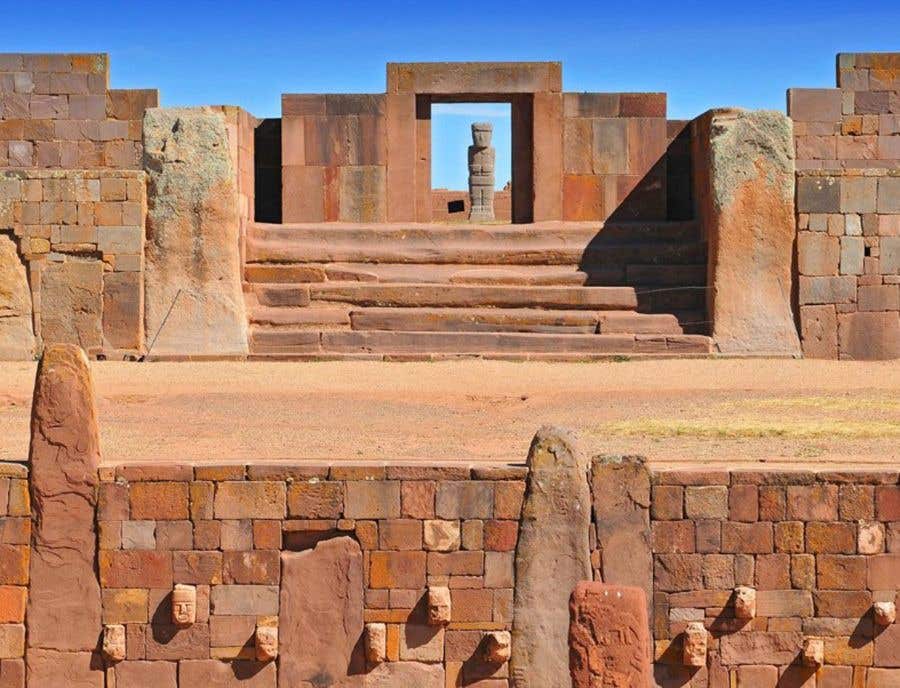

An ancient temple hidden in Bolivia’s highlands is reshaping how archaeologists understand the Tiwanaku civilization, a once-powerful culture that flourished near Lake Titicaca more than 1,000 years ago. A new study, published in the journal Antiquity, details the discovery of a massive ritual complex atop a remote hill once used by Indigenous farmers. The structure, now called Palaspata, helps fill in key gaps about how Tiwanaku expanded beyond its heartland and controlled distant trade routes.

At its peak around 1000 CE, Tiwanaku was a dominant Andean society with a complex social system and monumental architecture. Though scholars have long debated the extent of its influence beyond Lake Titicaca, the size and style of the newly uncovered temple suggest a deliberate push by Tiwanaku elites to govern movement and trade between the highlands and eastern valleys. The site provides strong evidence of state-level investment and regional control.

A Civilization Shaped by Ritual and Trade

Tiwanaku began as a farming village and eventually grew into a sophisticated urban center with terraced temples and massive stone monuments. Its ceremonial core featured carefully designed temples made with carved blocks, some weighing several tons. Researchers believe this architectural investment reflects a highly structured political and religious system that reached far beyond local borders.

For decades, scholars argued over whether Tiwanaku’s political system was centralized like an empire or more decentralized, governed through loose alliances and trade. Early ideas viewed Tiwanaku as a purely religious gathering site. Others later pointed to agricultural planning and hierarchical leadership as the keys to its power.

Recent research adds another layer: Tiwanaku may have managed inter-regional trade routes and used monumental architecture to cement political control across distant regions.

That view gains support from the discovery of the Palaspata complex, about 130 miles southeast of the main Tiwanaku ruins. Located at a strategic crossroads, the site sits between Lake Titicaca’s highlands, the llama-herding Altiplano to the west, and the fertile valleys of Cochabamba to the east. According to lead author José Capriles of Penn State University, this crossroads likely served as a key hub for moving goods and people.

"People moved, traded, and built monuments in places of significance," Capriles said. “This temple was one of them.”

Related Stories

A Lost Temple in Plain Sight

While the area had been known to locals for generations, its archaeological value had not been studied until a highway expansion required a cultural impact survey. That effort led researchers to reexamine a plateau near the Cayhuasi River, where they uncovered ceramics and burial sites dating back over 1,400 years.

Further investigation revealed the Palaspata temple — a massive quadrangular structure measuring about 125 by 145 meters. From above, satellite images and drone surveys helped bring out the faint outlines of walls, enclosures, and a central sunken courtyard. By applying photogrammetry to these images, the team reconstructed a detailed 3D model of the temple’s layout and elevation.

Fifteen modular enclosures surrounded the central plaza, each between 358 and 595 square meters. The entire complex was built with a combination of red sandstone and polished white quartzite boulders. Many stones were carved and aligned to follow the solar equinox, which would have held deep symbolic meaning in Tiwanaku cosmology. Capriles believes this orientation and scale point to religious rituals involving feasts, offerings, and community gatherings.

Excavated pottery fragments included keru cups — traditionally used for drinking chicha, a fermented maize beer — along with incense burners and other ceremonial items. The ceramics were decorated with classic Tiwanaku motifs, while others came from distant valleys, suggesting cultural exchange and trade across the Andes.

“The temple served both as a religious space and a political checkpoint,” Capriles explained. “Its position let it connect and control the movement of goods, people, and traditions between distinct ecological zones.”

Excavations Uncover a Multifunctional Settlement

The Palaspata complex didn’t stand alone. Excavations also focused on nearby areas called Cayhuasi and Ocotavi 1, located along the modern highway and Cayhuasi River. These areas turned out to be part of a larger settlement that covered at least 75 hectares — about the size of 140 football fields.

At Ocotavi 1, archaeologists opened a 10 by 70 meter grid where they found a mix of burials, trash middens, and domestic structures. Three flexed burials were discovered in stone-lined pits. Two adults had elongated skulls, a sign of intentional cranial modification, while the youngest was buried in fetal position with copper fragments and a decorated Tiwanaku bowl.

In total, researchers cataloged more than 2,000 bone fragments, most from domesticated llamas and alpacas. A few belonged to wild animals like deer, birds, or amphibians, showing that people relied on both herding and foraging. Tools made of bone, obsidian, and basalt were also common.

Charcoal samples helped date the site’s earliest activity to around AD 480. The most intense use came between AD 630 and 950, during Tiwanaku’s height. A later reoccupation occurred around AD 1240, after Tiwanaku’s collapse.

Ceramic finds were especially revealing. Many matched styles from the Cochabamba valleys, such as Tupuraya and Tricolor Cochapampa, confirming eastward ties. The presence of turquoise beads, marine shells from the Pacific, and exotic lithics points to long-distance exchange networks.

“The fact that maize was grown far away and yet used in ceremonies here highlights how trade was essential,” said Capriles. “These people found ways to move resources across difficult terrain.”

A Center of Cultural Exchange and Control

The temple complex atop the ridge was likely used for more than ceremonies. Its design and visibility suggest it functioned as a symbol of Tiwanaku’s authority — a gateway node that marked their territorial reach. Artefacts scattered across eastern terraces include eroding slab tombs, storage jars, and more ceremonial wares. A funerary tower near the southern edge hints at continued use into the post-Tiwanaku era.

This blending of domestic life, ritual, and trade underscores Tiwanaku’s flexible strategy in managing distant regions. In some places, they built full colonies, like in Peru’s Moquegua Valley, where highland migrants settled and built temples. In others, such as Chile’s Atacama Desert, their influence came through elite goods and ritual objects rather than direct control.

Palaspata falls somewhere in between. It wasn’t just a place to worship or rest during travel. Its monumental scale, symbolic orientation, and hybrid material culture suggest it was built with state resources to mark control over eastern routes.

Justo Ventura Guarayo, mayor of the local Caracollo municipality, said the discovery offers a new way for the community to connect with its history.

“This is vital for our region,” he said. “We’re working with state officials and archaeologists to protect the site and encourage tourism.”

Rediscovering a Civilization’s Reach

For archaeologists, Palaspata opens new questions about Tiwanaku’s rise and fall. It shows that political control wasn’t always enforced through conquest or colonization. Sometimes, it came by controlling connections — roads, trade routes, and shared rituals.

Much of Tiwanaku’s past remains hidden beneath fields or mistaken for natural hills. The fact that Palaspata had remained undocumented for so long shows how much more there is to find.

“With more insight into the past, we see how people managed cooperation and control,” said Capriles. “There’s still so much out there — we just have to open our eyes.”

Note: The article above provided above by The Brighter Side of News.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.