Cars and planes could avoid hazardous ice, freezing rain with new sensors

Researchers tested a two-sensor system that can spot hazardous icing clouds in seconds and confirm ice buildup on surfaces.

Edited By: Joseph Shavit

Edited By: Joseph Shavit

Nilton Renno mounts the infrared sensor onto his car, to test how well it performs on a snow-covered, residential road. (CREDIT: Jeremy Little, Michigan Engineering)

Icy weather can turn routine travel into a high-risk gamble. On roads, ice causes about 20% of weather-related car crashes each year. In the sky, ice buildup contributes to roughly 10% of fatal air carrier crashes by disrupting aerodynamics and flight controls. A University of Michigan team now says a paired sensor system could give pilots, drivers and automated safety systems earlier warning.

Nilton Renno, a University of Michigan professor of climate and space sciences and engineering, led the work with support from the National Science Foundation. Renno is also a professor of aerospace engineering and a pilot. His team reports the results in the journal Nature Scientific Reports after testing the sensors in a single-engine airplane and a light business jet equipped with scientific reference instruments.

“More people are traveling by plane each year, and there’s more pressure to fly in all weather conditions,” Renno said. “Our technology can help airplanes, drones, cars and trucks be as safe and efficient as possible.”

Recent crashes show what can happen when ice wins the race against detection and response. A flight from Brazilian airliner Voepass Linhas Aéreas crashed near São Paulo on Aug. 9, 2024, after the plane’s de-icing systems failed, according to a report in the Aviation Safety Network. An Air France flight also crashed in the Atlantic Ocean on June 1, 2009, after ice blocked the probes that measure the plane’s speed. In both cases, all occupants died.

Why ice is still hard to spot fast enough

Ice can build quietly, then turn dangerous fast. When an aircraft enters clouds with supercooled liquid water, ice can stick to key surfaces and change how the plane flies. That risk pushed regulators to tighten standards over decades. In the United States, the Federal Aviation Administration requires aircraft makers to show that new designs can fly safely in icing conditions defined in regulations. Since 1994, the FAA has issued hundreds of Airworthiness Directives tied to icing safety for more than 50 aircraft types.

Even with rules, the immediate challenge stays the same. You need to know what you are flying through, and you need that answer quickly.

Today’s common ice detectors often rely on probes that stick out from the aircraft. Those probes measure ice buildup on themselves, not on the wing, stabilizer or control surfaces where ice can be most dangerous. They also can struggle when outside air temperatures sit near 0°C. Airflow can warm the probe, and freezing releases heat, which can reduce how efficiently the probe collects ice. A flush sensor on a critical surface avoids some of those weaknesses because it checks the surface you care about.

Two sensors, one goal: warn early and confirm buildup

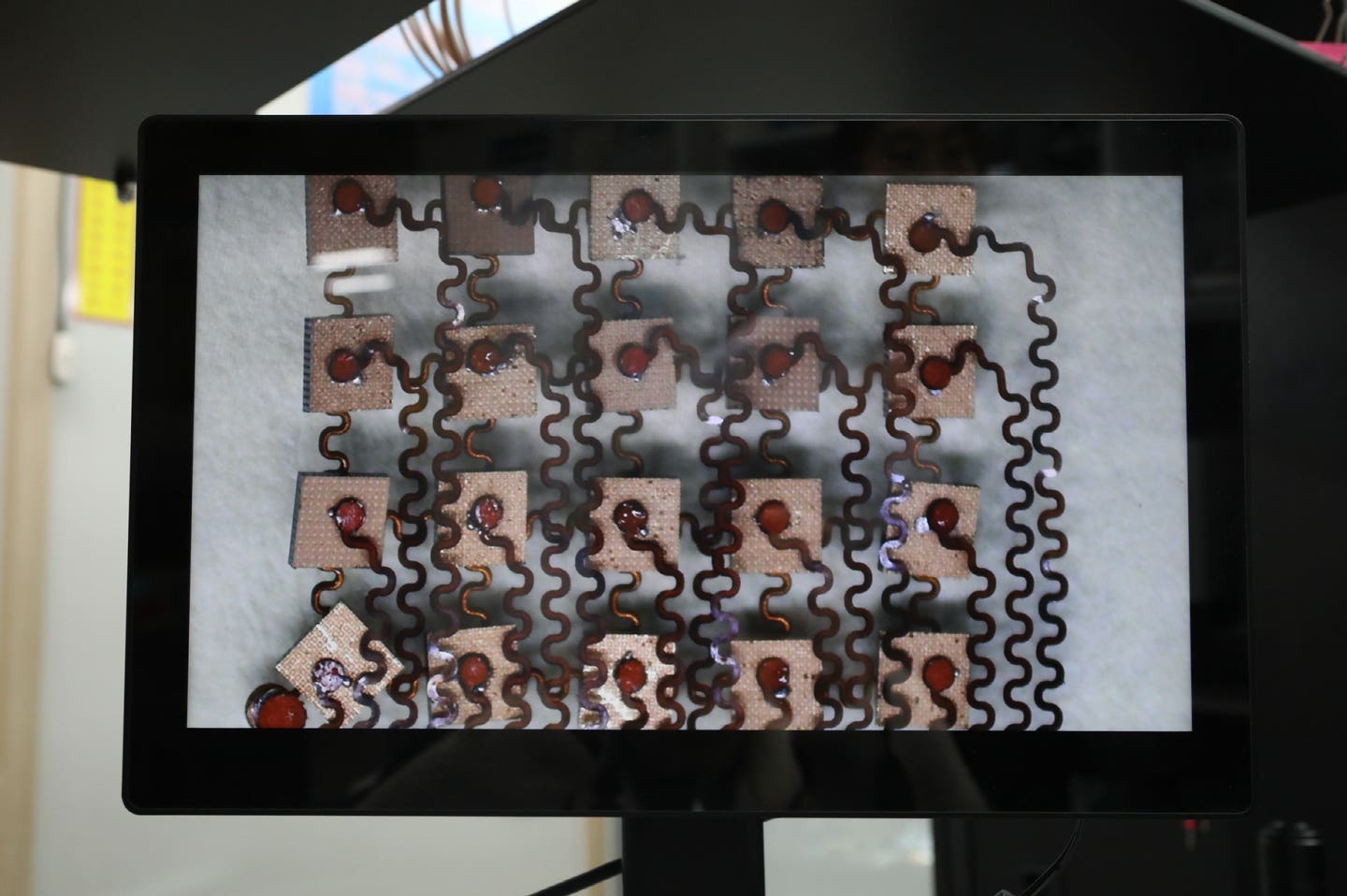

Renno’s system uses two complementary devices. One lies flush against the aircraft skin and uses microwaves to detect ice forming directly on the surface. The other uses lasers to examine the cloud ahead and flag freezing rain or large supercooled drops before heavy ice forms.

The microwave device tracks how its signal changes when water or ice covers it. In flight tests, the team focused on resonance frequency changes to indicate accretion. Laboratory work and simulations suggested it could detect ice thinner than 0.3 millimeters, a threshold tied to a cited requirement. During flight, radio-frequency noise prevented reliable use of a second metric, called quality factor, so the reported results relied on frequency shifts.

The laser-based unit aims to answer a different question: what kind of cloud are you entering? It fires three infrared lasers at different wavelengths and analyzes the return signals. Two beams interact differently with liquid water and ice, so the ratio of the returns can indicate whether the cloud holds ice particles, liquid droplets or a mix. That matters because planes usually ice up when they hit liquid drops that are chilled below freezing. Ice particles tend to bounce off.

The third laser helps estimate droplet size and droplet amount. Bigger drops pose a higher threat because they are more likely to strike the aircraft. Smaller drops more often ride airflow around the airframe. In tests, the optical system could spot freezing rain within seconds of entering a cloud.

Meeting tougher icing categories

Certification standards group icing clouds into “flight certification envelopes.” The long-standing category, known as Appendix C, covers common icing in stratiform and cumuliform clouds. Regulators later added Appendix O for less common but more hazardous conditions tied to supercooled large droplets, including freezing drizzle and freezing rain.

In simple terms, droplet size helps separate the categories. Once drops exceed roughly the Appendix C maximum, the environment is treated as more hazardous. Under the conservative approach described in the study, encountering a median volume diameter above about 40 micrometers points to Appendix O if the conditions persist long enough.

"To judge performance, our research team tested the system on an Embraer Phenom 300 research aircraft. Scientific instruments onboard measured droplet sizes and water content for comparison. Those reference measurements carried notable uncertainty, including about ±20% for median volume diameter and up to about ±40% for water content in some conditions. The laser unit sampled a large volume about 50 meters ahead, while reference probes sampled tiny volumes near the aircraft, so comparisons used 120-second averages to reduce mismatch," Renno shared with The Brighter Side of News.

Results showed the laser unit separated Appendix C from Appendix O quickly, within seconds of entering clouds. The microwave sensor then confirmed when ice started building on the surface, including during Appendix O encounters marked by abrupt frequency decreases. In a couple of cases, the microwave sensor suggested accretion when the flight log did not. One likely occurred in freezing drizzle. Another happened after takeoff, when ice may have formed as the plane moved from a warm, humid hangar into outside air.

The technology grew from an earlier space problem. After the Phoenix lander mission found evidence for liquid water on Mars, Renno wanted tools that could measure moisture in soils and distinguish water from ice. Later, he saw ice covering his own airplane one winter and turned that idea toward aviation safety.

“Icing of airplanes is a worldwide problem that can happen anytime of the year with aircraft of all sizes, depending on the flight altitude,” Renno said. “I realized that that was a problem that I could do something about because of my background as both a pilot and an atmospheric scientist.”

Practical Implications of the Research

If the paired sensors mature and earn certification, you could get earlier warnings about hazardous icing clouds and faster confirmation of ice buildup on critical surfaces. That could shorten the time between first detection and escape, a window where icing can shift from manageable to catastrophic.

On roads, the optical sensor could also warn drivers of black ice before a slide begins, or trigger automatic safety systems. “You can save a lot of lives by just slowing down when you detect a slippery road ahead,” Renno said. The study notes research showing that slowing by 4-9 miles per hour can cut the risk of serious injury in crashes by half.

The work also points to near-term engineering needs. The optical unit needs better internal temperature control to limit signal drift. The microwave unit needs lower radio-frequency noise so it can use quality factor to help distinguish ice, water and deicing fluid, and to estimate ice thickness. Those upgrades could broaden uses for drones, trucks and other vehicles.

Research findings are available online in the journal Scientific Reports.

Related Stories

- Simple printed signs can hijack self-driving cars and robots

- OmniPredict AI can help cars accurately predict pedestrian behaviors

- Toyota's self-driving EV bubble car for kids turns heads in Japan

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.

Joshua Shavit

Writer and Editor

Joshua Shavit is a Nor Cal-based science and technology writer with a passion for exploring the breakthroughs shaping the future. As a co-founder of The Brighter Side of News, he focuses on positive and transformative advancements in technology, physics, engineering, robotics and astronomy. Joshua's work highlights the innovators behind the ideas, bringing readers closer to the people driving progress.