Complex building blocks of life form spontaneously in space, study finds

Space radiation can help glycine form peptide-like molecules on icy dust grains, boosting the odds that young planets inherit key ingredients for life.

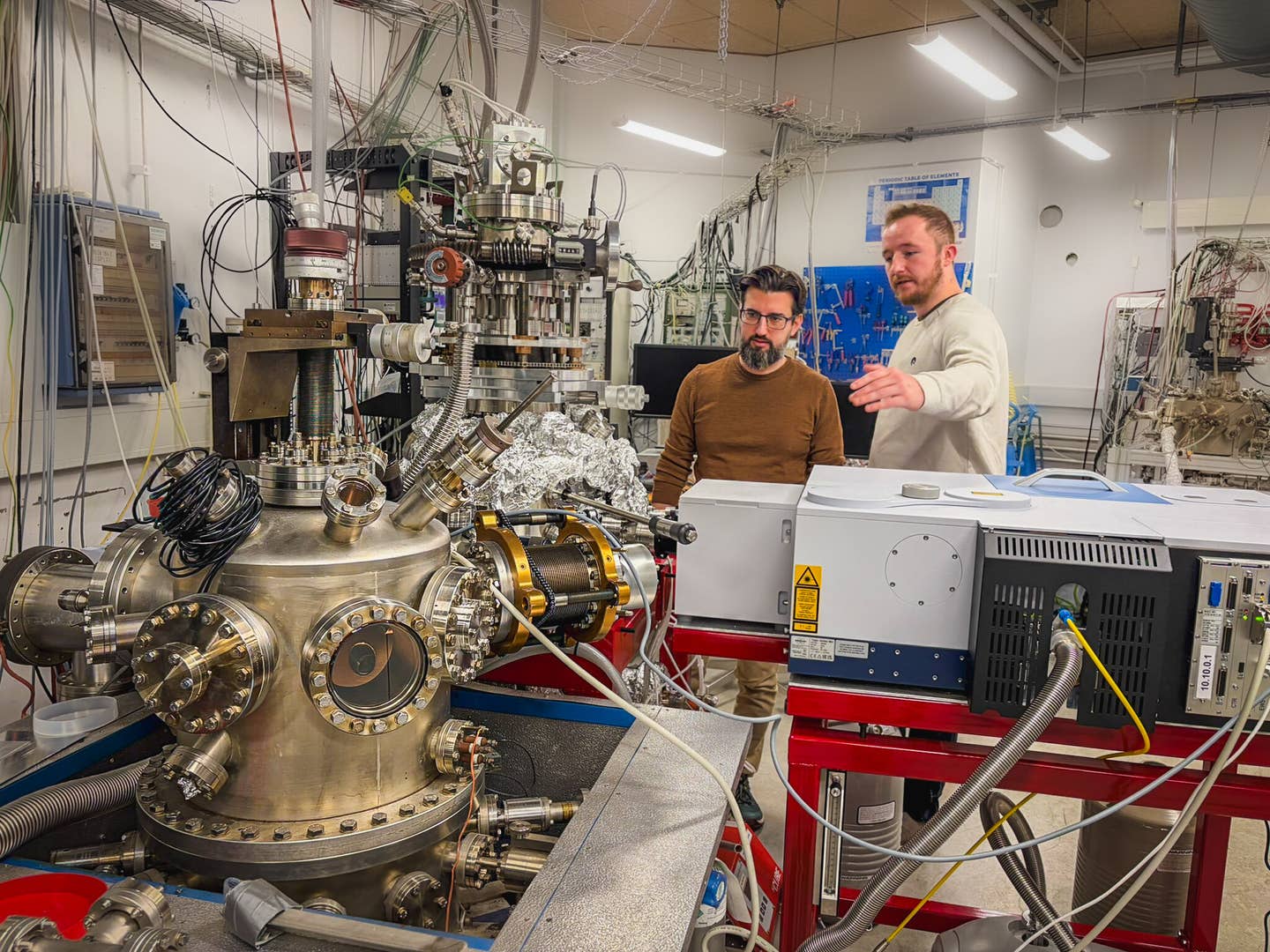

In the background, Associate Professor Sergio Ioppolo (left) and Postdoc Alfred Thomas Hopkinson (right) discussing experimental plans. In the foreground, two ultra-high vacuum chambers used to investigate reactions under interstellar medium conditions. (CREDIT: Dr. Signe Kyrkjebø, Aarhus University)

The chemical foundations of life could be found in the frigid pockets of molecular clouds that exist in the space between stars, rather than on any planetary bodies. At the University of Aarhus in Denmark and HUN-REN Atomki, an institution located in Hungary, researchers Sergio Ioppolo and Alfie Hopkinson sought to recreate the conditions found in space. They sought to determine if the process of forming peptides from amino acids could occur through chemical processes similar to what takes place between dust grains in the interstellar medium.

To create an environment similar to interstellar space, the team built a small experimental chamber where they placed glycine, the simplest form of an amino acid, in the chamber, which was kept at -260 °C. The reaction between the glycine and radiation was similar to that which occurs on the surface of dust grains in interstellar space.

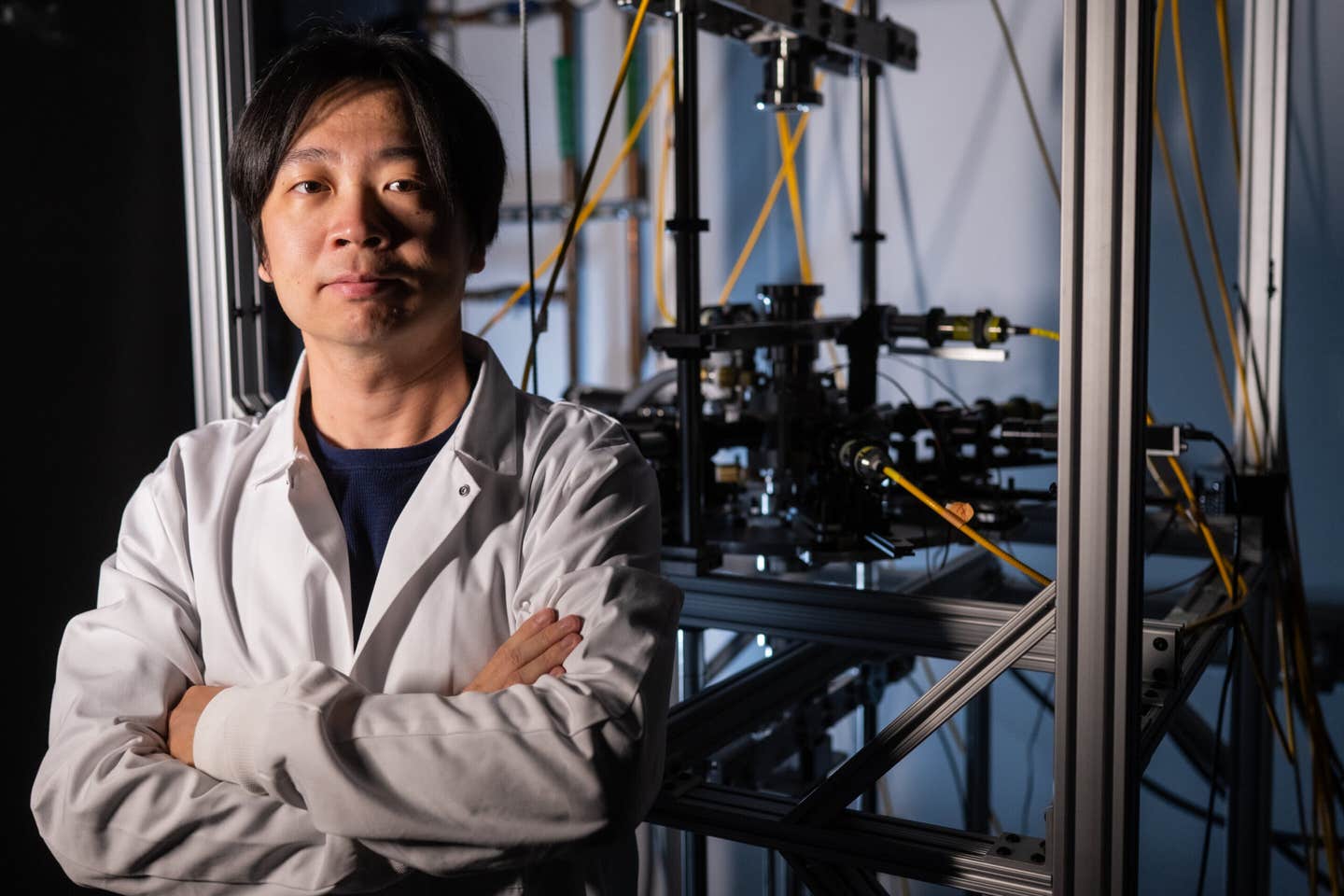

“Previous research has demonstrated that simple amino acids, such as glycine, can be produced in interstellar regions. However, our current investigation is focused on the potential for developing more complicated molecules (like peptides) from amino acids that are formed in interstellar regions prior to their involvement in stellar and planetary formation,” said Sergio Ioppolo.

From single amino acids to early chains

The creation of a peptide occurs when two or more amino acids join together; protein synthesis is when various peptide chains are combined to create a single protein, and the process of combining peptides is referred to as protein folding. Since proteins play such a crucial role in sustaining life, the formation of the peptide bond is regarded as a significant event that contributes to the transition from inorganic to organic.

To investigate the feasibility of glycine ice synthesis via radiation in other celestial bodies, the researchers at HUN-REN Atomki (Ioppolo and Hopkinson) simulated cosmic rays using an ion accelerator. The protons generated by the accelerator acted as an analogue for high-energy particles found within outer space, that is, the protons used in their experiments. The next step in the process was to record what happened to the glycine following this type of interaction.

Alfred Thomas Hopkinson stated, “Upon irradiation, it became apparent that glycine molecules began to interact with one another through the formation of peptide bonds, with water as a byproduct. This strongly suggests that a similar set of reactions occurs in interstellar molecular environments.”

Building space in a chamber

One unique aspect of this research was that it demonstrated how water could be used as a marker in determining whether or not peptide bonds have been produced through the formation of amide bonds. It was demonstrated that when an amide bond is created, the reaction produces water as a product.

The second part of this investigation emphasised glycine freezing at an ambient temperature of approximately 20 K on specifically designed windows that are employed in the infrared measurements of glycine. The team also evaluated three different forms of glycine, each having varying numbers of hydrogen atoms replaced with deuterium atoms, for the purpose of tracking the quantity of water produced during the glycine synthesis and subsequently interpreting the most likely route of formation for each.

Using protons at different energy levels, the research team monitored changes in the infrared signatures of glycine after irradiation with proton beams and as a result of the formation of new compounds through irradiation. Evidence suggested that many of the resulting compounds had resulted from the breakdown of glycine. Researchers observed a marked increase in CO₂ and CO signals, consistent with glycine fragment formation due to energetic impacts. A related increase in cyanate ion signal is also reported, which agrees with known space ice chemical processes.

"Our team found that in addition to producing free radical products through irradiation, that is, the destruction of glycine, irradiation can also create new covalent bonds between molecules," Ioppolo told The Brighter Side of News. "Water signals associated with the destruction of glycine rose significantly during the course of the experiment. In particular, deuterated glycine molecules had better resolution with respect to the water signal. The trend in the data supports the hypothesis that irradiation capable of destroying glycine is also capable of assisting in the formation of new covalent bonds," he continued.

Following water to identify the reaction

The mass spectrometric analyses of material that evaporated from the irradiated ice confirmed that the material consisted predominantly of water (H₂O, D₂O, and HDO) and/or other products formed as a result of the radiation-induced breakdown of glycine.

Through tracing the isotopic composition of both products, it was possible to distinguish likely sources of water produced during the experiment. The two potential pathways include: (1) the destruction of carbon dioxide, which results in the generation of oxygen free radicals that subsequently combine with hydrogen from carbon monoxide to produce H₂O, and (2) peptide bond formation, during which time H₂O is liberated.

By examining how quickly the various isotopes of water formed in each sample, the authors concluded that peptide formation likely contributed to the production of water in addition to the pathways involving the generation of oxygen free radicals from the breakdown of carbon dioxide. They tested higher-energy simulated galactic cosmic ray irradiation and, through these tests, determined that the chemistry of glycine continues to produce larger and more complex organic molecules.

Evidence for peptide-like products

The residue exhibited infrared characteristics resembling amide particulate molecules, defined as hydrocarbon chains having an amine tail. The researchers caution that it is possible that amide bands are not automatically indicative of the presence of peptides, since other carbonyl compounds may also produce similar effects; however, the presence of amide bands corresponding to the production of H20 lends greater reasoning to the existence of peptide bond formation under cold, saturated, irradiated conditions.

The most concrete evidence of peptide-like substances was obtained via spectrometric analysis after the residue was dissolved in a solvent. In addition to the expected presence of glycine, the researchers observed a signal compatible with glycylglycine, which is recognized as the simplest of all dipeptides, comprising two glycine molecules.

Furthermore, the authors also observed the presence of substantially greater numbers of mass transference than would be predicted, indicating that upon being subjected to irradiation, the material produced a much more diverse combination of organic molecular compounds.

The results of this study are relevant to previous questions posed about amino acid production from bodies of meteoritic origin or comet tails and suggest that organic molecules related to the development of life on Earth may have formed naturally in interstellar space.

The more difficult query, however, continues to be what happens to the amino acids produced following irradiation, given that amino acids are susceptible to destruction from irradiation. The findings of this study suggest a more complex view of radiation from space, namely, how radiation from interstellar sources can both destroy and produce biological components found on the surfaces of other celestial bodies.

Where stars are born, chemistry begins

The formation of new star systems commences as the surrounding molecules change chemically, accompanied by the birth of new stars. While many early scientists assumed for several years that only basic, simple molecules were produced in those environments, larger, more complex molecules were thought to develop later as planets were beginning to form and were formed.

“The original theory was that only the simplest of molecules could form in these clouds, and the more complicated molecules would form later during the development of a star from a disc of combined gas,” says Sergio Ioppolo. “But, as we have demonstrated previously, this is not at all an accurate statement.”

If peptide-like molecules can develop early, then young planets may possess more robust chemistries than scientists originally thought.

“As the gas clouds collapse into stars and planets, slowly, the building blocks of life will accumulate on rocky planets within the new solar systems. If those planets are within the habitable zone of their stars, the likelihood of creating life will increase significantly,” says Sergio Ioppolo.

“While we do know that the precise method by which life emerged on Earth is still under investigation, it is certainly true that many of the prebiotic building blocks for life were formed naturally in outer space.”

A bigger map of prebiotic ingredients

Hopkinson stresses the fact that the chemistry leading to bond formation is not restricted to glycine only. “All types of amino acids bond into peptide chains through identical reactions; thus, there is a strong possibility that other peptides will also form naturally in the vast space between the stars,” states Hopkinson. “We are currently researching the composition of interstellar ice. We hope that, as our understanding improves, our research can help address some basic questions about whether or not these molecules will be used as building blocks for life as we currently know it.”

In addition to proteins, there are many other types of building blocks. Cells use membranes and other molecules, including nucleobases and nucleotides. Our research team is part of Aarhus University’s Center for Interstellar Catalysis (InterCat), which has been funded by the Danish National Research Foundation. In this center, we are interested in studying how an environment in space might generate different types of prebiotic materials.

“Some of these molecules are critical components for building life,” said Professor Liv Hornekær, who is the center leader of InterCat. “They could have a role in prebiotic chemistry and catalyzing reactions towards creating life.”

Sergio Ioppolo continues to explain, “There is still much to be learned; however, we are currently working on determining the answers to as many of these basic questions as possible. We have already determined that many components of the building blocks of life were made out in space, and it is very likely we will continue to find more in the future.”

Practical implications of the research

Researchers are able to use these findings to reshape their thinking regarding the chemical “starter kit” that younger planets may acquire. For example, if amino acids are joining to create peptide-like molecules on icy dust grains in the interstellar medium, this implies that prebiotic chemical evolution on a planet is likely to begin much sooner than previously thought. Thus, this provides an impetus to search for components of life not only in the late stage of planetary formation, but also in the less evolved and colder areas of molecular clouds and protoplanetary disks.

The results obtained from this research may also direct future investigations in the laboratory or through space. Researchers can utilize water production, isotopic analysis, and peptide-like signatures for future investigations of amino acids and other mixtures that may be representative of interstellar ices.

As time progresses toward more sophisticated telescopes, researchers will be able to create a better connection between telescope data, meteorite chemical analysis, and laboratory chemical data that will explain the processes through which complex organics survive, move, and accumulate onto habitable planets.

Research findings are available online in the journal Nature Astronomy.

Related Stories

- Phosphorus from space could help explain the origins of life on Earth

- Life on Earth may have come from outer space, study finds

- Did life on Earth come from outer space? Study provides new insights

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.

Joseph Shavit

Writer, Editor-At-Large and Publisher

Joseph Shavit, based in Los Angeles, is a seasoned science journalist, editor and co-founder of The Brighter Side of News, where he transforms complex discoveries into clear, engaging stories for general readers. With vast experience at major media groups like Times Mirror and Tribune, he writes with both authority and curiosity. His writing focuses on space science, planetary science, quantum mechanics, geology. Known for linking breakthroughs to real-world markets, he highlights how research transitions into products and industries that shape daily life.