Excitons Let Scientists Reshape Quantum Materials With Less Light

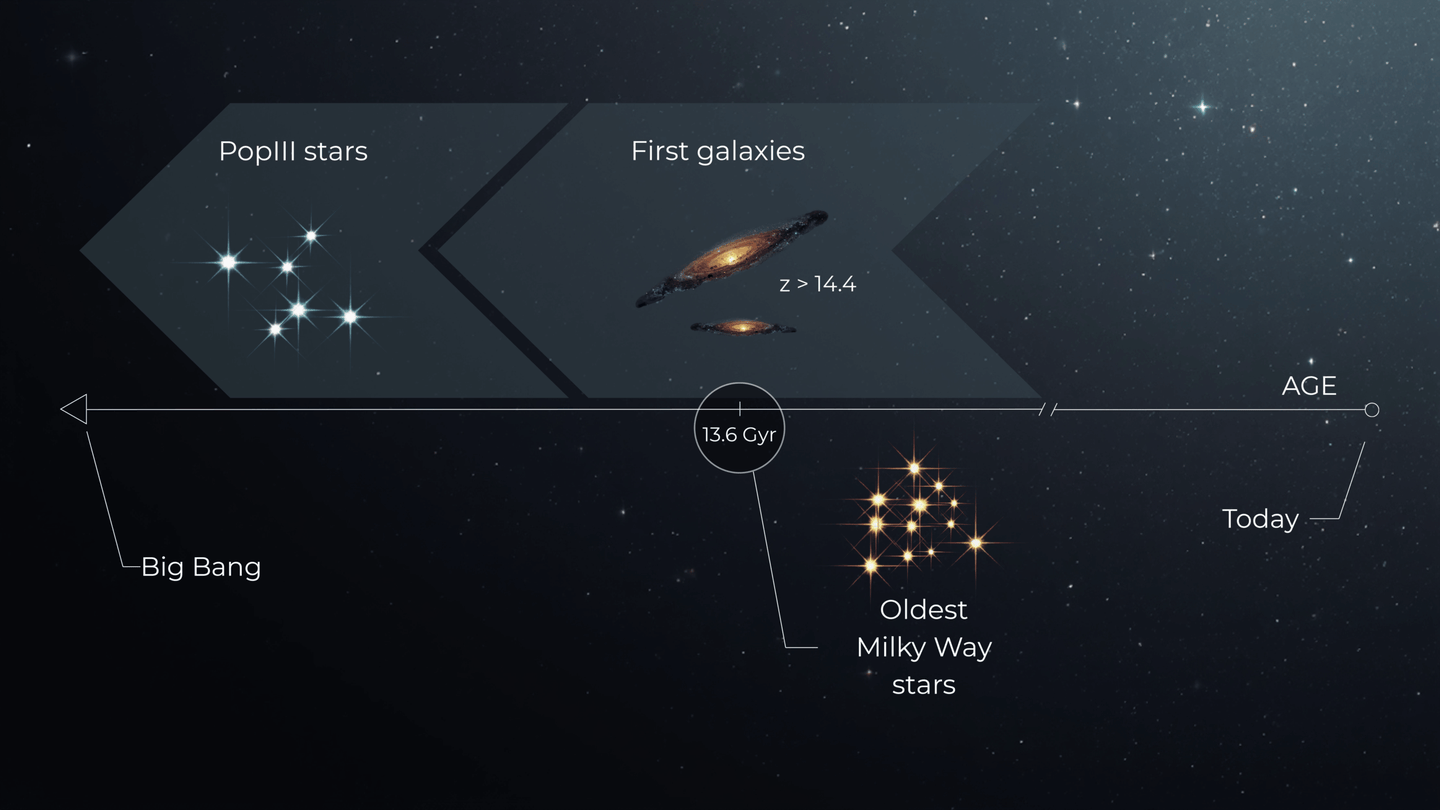

Floquet engineering aims to change a material’s electronic behavior with a repeating drive. Researchers show excitons can do the job far better than intense laser fields.

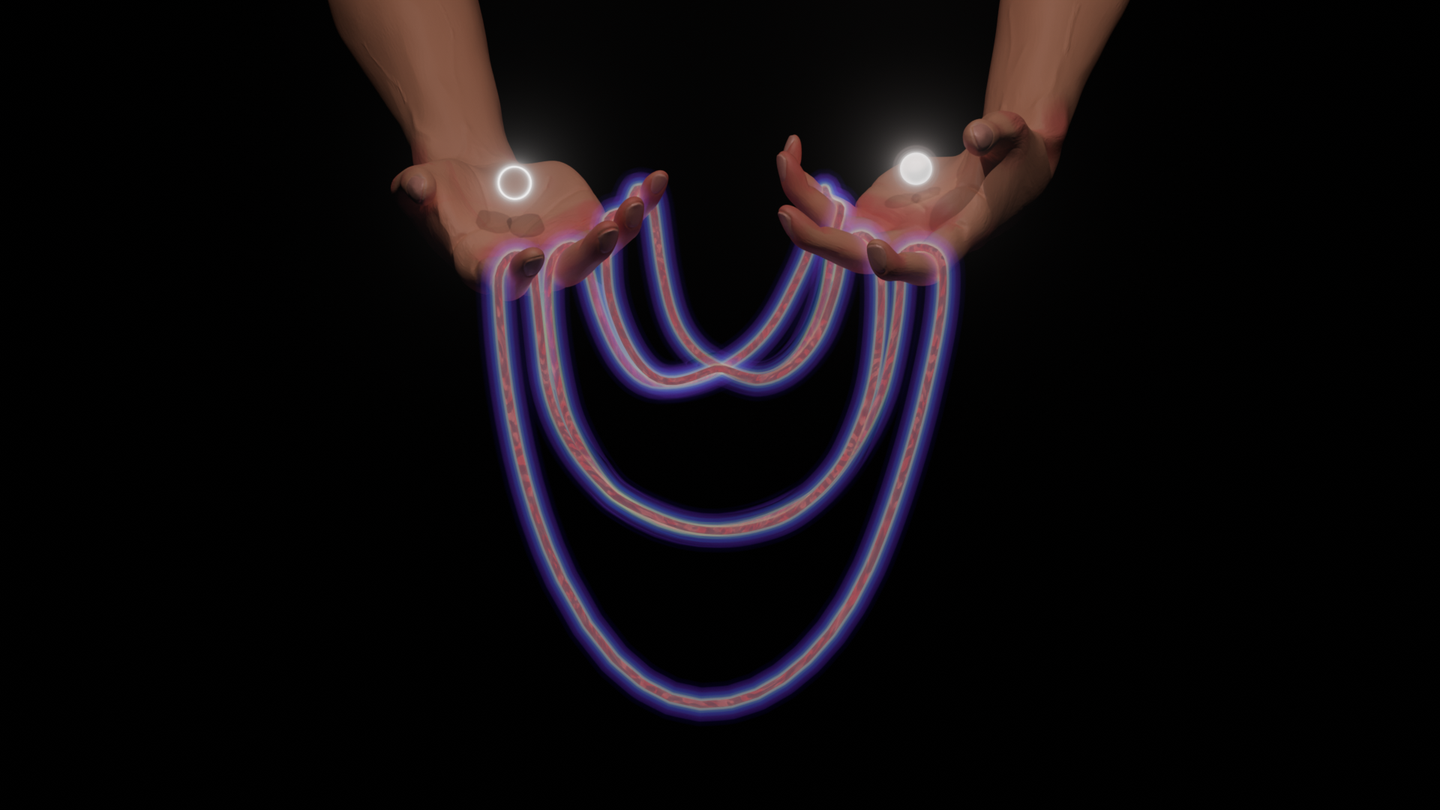

A 3D rendering of a pair of hands holding glowing bands of energy like a cat’s cradle. One of the bands fold inwards, reminiscent of the Mexican-hat-like momentum dispersion indicative of Floquet effects. The glowing orbs above the hands, one dark and the other light, represent the electron and hole that together form an exciton. (CREDIT: Jack Featherstone)

Light can do more than illuminate a material. In some cases, it can temporarily change how electrons move through it. That possibility sits at the heart of Floquet engineering, a young area of condensed-matter physics that aims to create new electronic behavior on demand.

Now researchers co-led by the Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology and Stanford University report a way to make those changes far more efficient. Instead of relying on light’s oscillating electric field as the main driver, they use excitons, short-lived electron–hole pairs that form inside semiconductors. The team published its results in Nature Physics.

“Excitons couple much stronger to the material than photons due to the strong Coulomb interaction, particularly in 2D materials,” says Professor Keshav Dani from the Femtosecond Spectroscopy Unit at OIST, “and they can thus achieve strong Floquet effects while avoiding the challenges posed by light. With this, we have a new potential pathway to the exotic future quantum devices and materials that Floquet engineering promises.”

Turning a rhythm into new electronic behavior

"Floquet engineering starts with a basic idea: a repeating push can create a bigger, more complex response. A swing rises higher when pushes come at the right rhythm. In quantum materials, that rhythm can mix electronic energy states in ways a stationary crystal cannot," Dani explained to The Brighter Side of News.

"Crystals already impose a repeating structure in space, which shapes electrons into allowed energy bands. A second repetition in time can reshape those bands again," he continued.

Researchers often create that time rhythm with a laser field. The approach traces back to a proposal by Oka and Aoki in 2009, and later experiments have shown Floquet “replica” bands, plus hints of exotic phases such as Floquet topological insulators.

But light-driven Floquet work comes with a major practical problem. Light couples relatively weakly to matter, so experiments often need extreme intensities and ultrashort pulses. Those conditions can heat or damage samples. They also compress the useful signal into a narrow time window.

“Until now, Floquet engineering has been synonymous with light drives,” says Xing Zhu, a PhD student at OIST. “But while these systems have been instrumental to proving the existence of Floquet effects, light couple weakly to matter, meaning that very high frequencies, often at the femtosecond scale, are required to achieve hybridization. Such high energy levels tend to vaporize the material, and the effects are very short-lived. By contrast, excitonic Floquet engineering require much lower intensities.”

Letting the material drive itself

Excitons offer a different source of rhythm. When a semiconductor absorbs energy, an electron can jump from the valence band to the conduction band. The missing electron leaves a positively charged “hole.” The electron and hole bind into an exciton, which behaves like a bosonic particle.

Because excitons form from the material’s own electrons, they interact strongly with the surrounding electronic structure. Their internal, coherent oscillation can act like a built-in periodic drive, even after the pump light stops overlapping with the measurement.

“Excitons carry self-oscillating energy, imparted by the initial excitation, which impacts the surrounding electrons in the material at tunable frequencies. Because the excitons are created from the electrons of the material itself, they couple much more strongly with the material than light. And crucially, it takes significantly less light to create a population of excitons dense enough to serve as an effective periodic drive for hybridization – which is what we have now observed,” explains co-author Professor Gianluca Stefanucci of the University of Rome Tor Vergata.

The new results focus on monolayer WS2, an atomically thin semiconductor where excitons are unusually strong. The team used time- and angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy, known as TR-ARPES, with a time-of-flight momentum microscope that records energy and momentum at once.

They measured a pristine region about 16 micrometers by 16 micrometers at 100 K. In the unperturbed map, the valence-band maximum appears at the K point, with a 450-meV spin splitting between the first and second valence bands at K.

From faint replicas to a dramatic band reshaping

The researchers first did a conventional optical Floquet test. They pumped the sample at 1.98 eV, about 120 meV below the A exciton resonance, and used s-polarized light to avoid unwanted photoemission effects. At zero pump–probe delay, they saw a weak replica of the valence band shifted upward by 1.98 eV. That replica lasted about 130 femtoseconds, consistent with the brief overlap of pump and probe. Even then, the optical-drive case showed no clear band hybridization.

Next, they switched to an excitonic drive. They pumped resonantly at 2.1 eV with a 100-fs pulse to create A excitons. To avoid contributions from the optical field itself, they recorded ARPES spectra 200 femtoseconds after zero delay, when the pump and probe no longer overlap. The setup aimed to capture a material that still holds a coherent exciton population.

At high exciton density, the team reported the study’s most striking feature: a Mexican-hat-like dispersion in the topmost valence band. The highlighted density for the strongest regime is nX = 3 × 10^12 cm−2. Instead of a simple inverted parabola around the K valley, the band shifts down at the center and reaches its maximum in a ring away from the valley center.

That change points to hybridization between the valence band and an exciton-dressed conduction band. A matching Mexican-hat-like shape also appears in a replica band about 2.1 eV above the valence band, aligning with the exciton energy. The conduction band itself remains hard to see because it is not occupied.

Why excitons outperform light, and what comes next

The team tested simpler explanations, such as free carriers or holes. They report that free carriers do not create the Mexican-hat-like shape. They also tracked how the signature evolves over time. The inferred exciton density decays with a lifetime of about 800 fs, while the Floquet-induced hybridization decays with a 470-fs time constant. Even so, the hybridization remains visible close to 1 picosecond. By around 2 ps, when coherence should fade, the Mexican-hat signature disappears.

They also varied exciton density at a fixed 200-fs delay. Across 4 × 10^11 cm−2 up to 3 × 10^12 cm−2, the hybridization magnitude scales linearly with exciton density. The first replica band intensity also scales linearly. Those trends fit the idea that coupling depends on excitonic polarization.

The comparison with optical driving is blunt. Under comparable conditions, the exciton-driven Floquet effects reach about two orders of magnitude stronger than the optically driven version, and they persist longer, on the order of a picosecond. In the exciton-driven regime, hybridization reaches around 80 meV. For the optical-drive case under the study’s conditions, the paper estimates hybridization near 1 meV, below experimental resolution.

“The experiments spoke for themselves,” says Dr. Vivek Pareek, an OIST graduate now a Presidential Postdoctoral Fellow at the California Institute of Technology. “It took us tens of hours of data acquisition to observe Floquet replicas with light, but only around two to achieve excitonic Floquet – and with a much a stronger effect.”

Exciton Condensates and Exciton Insulators

The work also links to a long-standing pursuit: exciton condensates and exciton insulators. The study argues that the exciton-driven Floquet picture matches the non-equilibrium exciton-insulator formalism, while offering an intuitive band-hybridization view.

To strengthen the interpretation, the team performed ab initio time-dependent adiabatic GW calculations for monolayer WS2. The computed spectra match experiments across an order of magnitude in exciton density. They reproduce momentum-localized replicas and the Mexican-hat-like dispersion.

The researchers also see a wider future. Excitons are one option among many bosonic excitations. In principle, phonons, plasmons, and magnons could serve as internal Floquet drives too. “We’ve opened the gates to applied Floquet physics,” concludes study co-first author Dr. David Bacon, a former OIST researcher now at the University College London, “to a wide variety of bosons. This is very exciting, given its strong potential for creating and directly manipulating quantum materials. We don’t have the recipe for this just yet – but we now have the spectral signature necessary for the first, practical steps.”

Practical Implications of the Research

This approach lowers a key barrier for Floquet engineering: the need for extreme light fields that can overheat or damage materials. By using excitons as the main driver, researchers can reach stronger band reshaping with less intense pumping, and they can observe effects for longer times, up to about a picosecond in this study. That longer window matters for designing experiments that do more than detect a signal, including attempts to control electronic properties in a repeatable way.

Over time, exciton-driven Floquet control could help researchers build “on-demand” electronic states that do not exist at equilibrium, including routes toward unusual phases linked to superconductivity, topology, or exciton-insulator behavior.

The results also suggest a broader strategy: use internal, coherent excitations to sculpt band structure with more precision in momentum space than a broad optical drive. If future work extends this idea to other excitations, it could expand the toolkit for quantum materials research and speed progress toward devices that rely on tunable electronic bands.

Research findings are available online in the journal Nature Physics.

Related Stories

- Dark excitons: Scientists make previously hidden states of light shine 300,000 times brighter

- New quantum battery breakthrough boosts energy storage by 1,000x

- Scientists achieve a major breakthrough in artificial photosynthesis

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.

Shy Cohen

Writer