Exercising this small leg muscle boosts metabolism, burns fat even while seated

A small calf muscle may unlock big health benefits—lowering blood sugar and fat levels—just by moving it while seated.

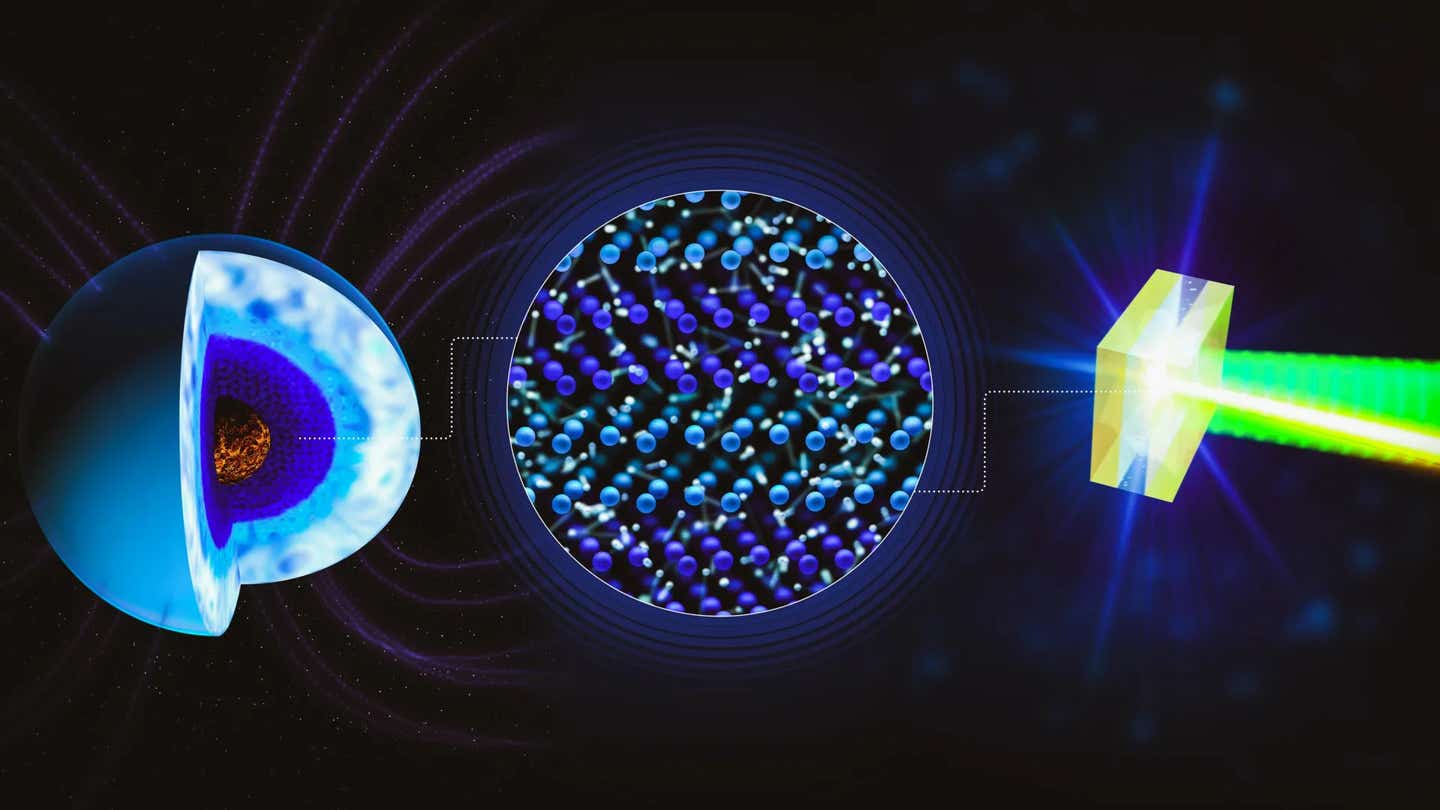

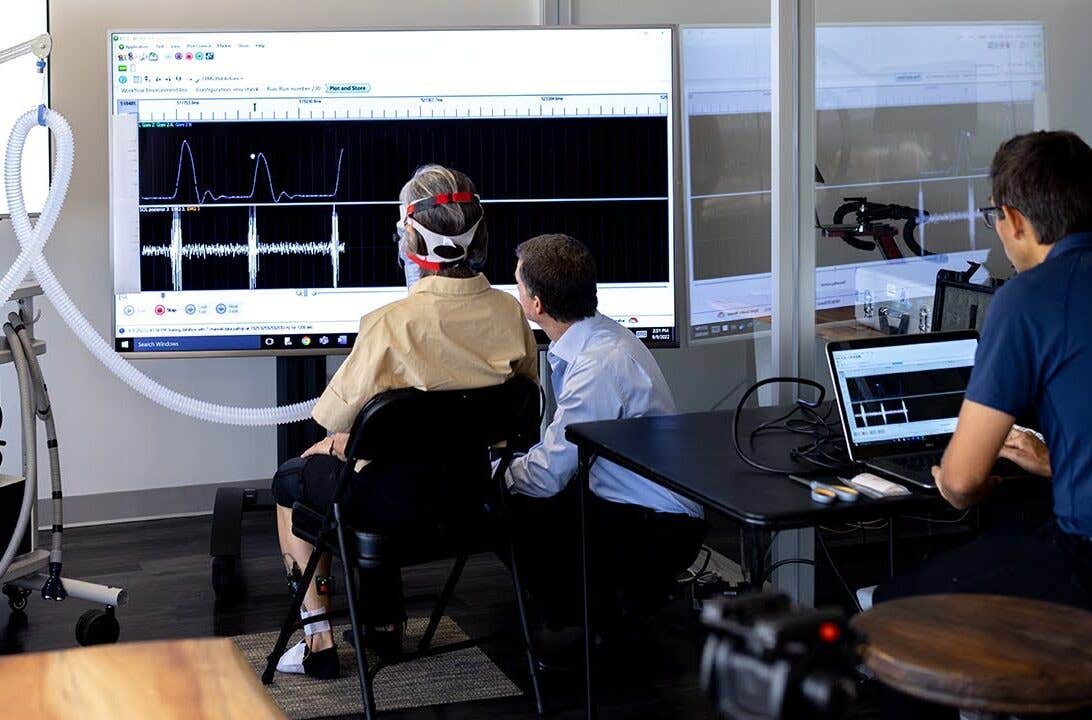

Scientists found that activating the soleus, a small calf muscle, through a seated movement called the soleus pushup, can dramatically improve blood sugar and fat metabolism. (CREDIT: University of Houston)

For decades, scientists thought skeletal muscle—the body’s largest lean tissue—played only a small role in regulating blood sugar and fat when you’re at rest. That assumption may now be changing, thanks to one overlooked muscle hidden in your calf.

A research team led by Marc Hamilton, professor of health and human performance at the University of Houston, discovered that this small but mighty muscle can transform the way your body manages energy. The soleus, a slow-twitch muscle tucked below the larger calf muscle, makes up only about 1% of your body weight. Yet when activated in a specific way while sitting, it can trigger powerful improvements in blood sugar control and fat metabolism.

The discovery, published in iScience, highlights a simple movement called the “soleus pushup,” or SPU. Unlike jogging, lifting weights, or cycling, the SPU is done while sitting and doesn’t require heavy effort. But the benefits it brings may rival or even surpass more familiar fitness strategies.

Why the Soleus Muscle Stands Out

The soleus has a rare profile compared to most of the body’s 600 muscles. Around 88% of its fibers are slow-twitch, which means they specialize in endurance and use oxygen efficiently. This unique design allows the muscle to keep working for hours without tiring.

Instead of depending heavily on its stored energy (glycogen), the soleus prefers to draw fuel directly from circulating blood sugar and fats. That detail matters. Because it taps into what’s floating around in your bloodstream, the muscle can run steadily without draining its own reserves.

It also has a dense vascular system and a high number of glucose transporters—molecular “doors” that let sugar flow from the blood into the muscle. Combined with enzymes geared for oxygen-based energy production, the soleus is perfectly suited to act as a steady, low-flame engine for metabolism.

Related Stories

- New drug boosts fat burning and increases muscle endurance without a workout

- 'Exercise in a bottle' drug helps the body burn more fat, use energy more efficiently

The Movement That Unlocks Its Power

Hamilton’s team developed the SPU to fully tap into the soleus’ potential. You sit with feet flat on the floor. Then, while keeping the front of the foot grounded, you raise your heel and let it fall back naturally.

On the surface, it looks like a basic seated calf raise. But internally, it’s different. The way the muscle contracts during an SPU draws primarily on blood-borne fuels, not muscle glycogen. That allows the soleus to keep working far longer than other muscles could.

“We never dreamed that this muscle has this type of capacity,” Hamilton said. “It’s been inside our bodies all along, but no one ever investigated how to use it to optimize our health, until now.”

In practice, people who learned the correct movement could sustain these contractions for hours without feeling drained. During that time, the soleus acted like a miniature furnace, burning through glucose and fats.

Experiments That Measured the Impact

To test the idea, Hamilton’s group designed controlled experiments with men and women of different ages and body types. On one day, volunteers performed SPUs while sitting. On another, they remained still under the same conditions.

The results were striking. During SPUs, oxygen use doubled compared to ordinary sitting, signaling that the muscle was burning far more fuel. Yet MRI scans showed it hardly touched its glycogen stores. About 80% of the added energy demand came directly from the soleus itself, which was remarkable for a muscle that accounts for little more than 1% of body mass.

In a follow-up trial, participants drank a sugary liquid—essentially a controlled glucose load—on separate test days with and without SPUs. Blood tests tracked sugar and insulin levels for several hours.

When people engaged their soleus muscle with SPUs, blood sugar spikes were reduced by 52%. Insulin needs fell by 60%, meaning the body managed sugar levels with much less effort. Fat metabolism also doubled during fasting windows between meals, and harmful triglycerides in the blood dropped.

Hamilton pointed out that these changes exceeded what many well-known approaches can achieve. Intermittent fasting, long walks, and even significant weight loss often show smaller or less consistent improvements.

“All of the 600 muscles combined normally contribute only about 15% of whole-body oxidative metabolism in the three hours after ingesting carbohydrate,” he explained. “Despite the fact that the soleus is only 1% of body weight, it is capable of raising its metabolic rate during SPU contractions to easily double, even sometimes triple, the whole-body carbohydrate oxidation.”

A Different Way of Thinking About Exercise

Many people believe that one workout a day can offset the hours spent sitting at a desk, in class, or on the couch. The reality is more complicated. During inactivity, most skeletal muscles stay metabolically quiet, burning very little sugar or fat. That helps explain why chronic conditions tied to metabolism, such as type 2 diabetes, continue to rise despite growing awareness of exercise.

By 2010, more than half of American adults were estimated to have prediabetes or diabetes, with rates reaching nearly 80% among people over 65. Combine those numbers with the fact that many adults sit for 9 to 11 hours daily, and it’s easy to see why researchers have looked for new strategies.

Hamilton and his colleagues argue that the answer isn’t more intense workouts, but smarter use of the body’s untapped resources. For years, scientists have tried to activate brown fat, a tissue that can burn calories and regulate metabolism. Yet brown fat is less than 1% of body weight and hard to consistently switch on. The soleus, by contrast, is present in everyone and can be targeted with a simple movement.

“We are unaware of any existing or promising pharmaceuticals that come close to raising and sustaining whole-body oxidative metabolism at this magnitude,” Hamilton said.

Making It Work in Daily Life

The SPU isn’t meant to replace traditional workouts like running, swimming, or strength training. Instead, it serves as a complement—something to weave into the hours you already spend sitting.

Because the movement relies on endurance rather than high intensity, it’s well-suited for older adults or people with health problems who struggle with conventional exercise. It doesn’t require special equipment or a gym visit, making it accessible to nearly anyone.

Still, learning the movement correctly matters. Hamilton’s lab currently uses wearable devices to help people optimize the SPU, ensuring they recruit the soleus rather than other calf muscles. His team plans to release more guidance in future publications so the general public can benefit without specialized tools.

“This is the first concerted effort to develop a specialized type of contractile activity centered around optimizing human metabolic processes,” Hamilton said.

What started as curiosity about an overlooked muscle has now become one of the most promising ways to counteract the hidden harms of too much sitting. Whether you’re in an office chair, at school, or at home, the soleus pushup offers a surprisingly powerful option for better metabolic health.

Practical Implications of the Research

The findings suggest a practical way to fight problems linked to prolonged sitting and poor blood sugar control. Since so many people spend most of their day seated, weaving SPUs into ordinary routines could help lower the risk of type 2 diabetes, heart disease, and other chronic conditions.

Future designs may include chairs, workstations, or wearables that encourage people to activate their soleus muscle while sitting. This research also opens a potential path for clinical care, giving people with metabolic disorders or mobility challenges a new tool to manage health without depending only on strenuous workouts.

Note: The article above provided above by The Brighter Side of News.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.