Giant dark matter ‘sheet’ may shape galactic motion in the Milky Way

New simulations suggest the Milky Way’s neighborhood sits in a vast sheet of matter, including dark matter, with large voids above and below.

Edited By: Joshua Shavit

Edited By: Joshua Shavit

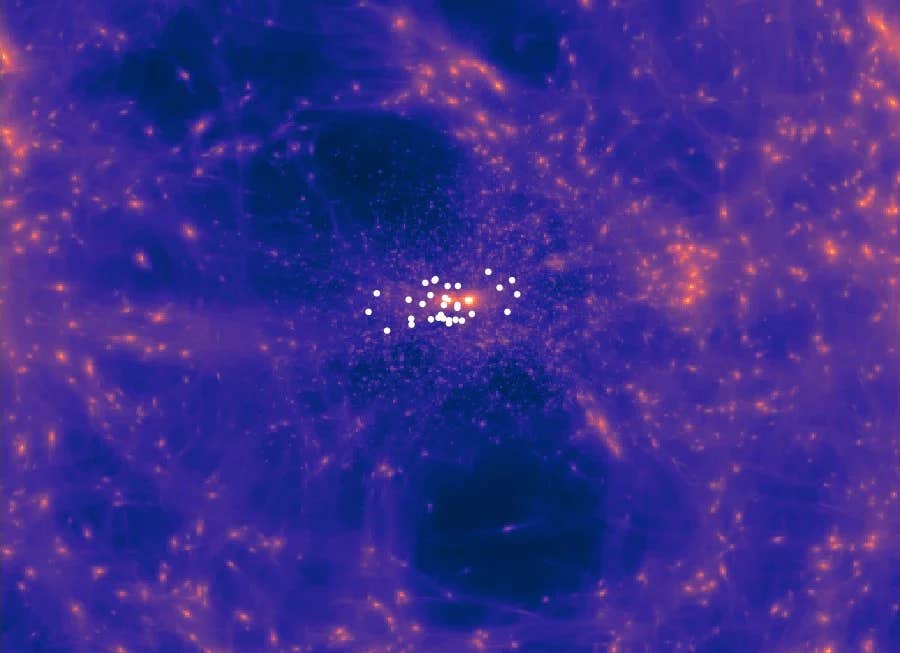

Simulations suggest dark matter near the Milky Way forms a vast sheet with voids above and below, explaining galaxy motions. (CREDIT: Nature Astronomy)

On a clear night, the Milky Way and the Andromeda galaxy look like close neighbors. In space, they really are. Andromeda is even heading your way at about 100 kilometers per second.

Now astronomers at the University of Groningen in the Netherlands say your galaxy neighborhood sits inside a much larger, pancake-like spread of matter, including dark matter you cannot see.

The work comes from Ph.D. graduate Ewoud Wempe and Professor Amina Helmi at Groningen’s Kapteyn Institute, with collaborators in Germany, France and Sweden. Their study appears in Nature Astronomy.

A flatter neighborhood than expected

For nearly a century, astronomers have known that most galaxies move away from the Milky Way as the universe expands. That trend is described by the Hubble-Lemaître law. But scientists have also struggled with a local mystery. Aside from Andromeda, many big nearby galaxies seem to drift away almost as if the Milky Way and Andromeda’s gravity barely slows them down.

Wempe and Helmi’s team says the key is not that gravity is weak. It is that the mass around your Local Group is shaped in a surprising way.

Their computer simulations suggest that most matter just beyond the Local Group is organized in a broad plane that stretches tens of millions of light-years. Above and below that plane are large, emptier regions called voids. With that setup, the observed speeds and positions of nearby galaxies finally make sense.

“This is the first assessment of the distribution and velocity of dark matter in the region surrounding the Milky Way and the Andromeda galaxy,” Wempe said. “We are exploring all possible local configurations of the early universe that ultimately could lead to the Local Group. It is great that we now have a model that is consistent with the current cosmological model on the one hand, and with the dynamics of our local environment on the other.”

Weighing the Local Group, two ways

Astronomers often “weigh” the Milky Way and Andromeda using their mutual motion. The idea, called the timing argument, treats the pair like two objects that started near each other after the Big Bang, separated, then slowed and began falling back together. When scientists first applied it in 1959, the answer was shocking. The pair seemed to contain far more mass than stars and gas could explain.

Today, the needed measurements are better. But the method still has a catch. It treats real galaxies like point masses moving on a simple path, even though each one sits in an enormous halo of matter.

A second method uses “tracer” galaxies outside the Milky Way and Andromeda. If you look far enough out, the two main galaxies can be treated as one combined mass. Then you compare a tracer galaxy’s speed to what it would be from cosmic expansion alone. The Local Group’s gravity should slow that outward motion.

Here is where tension builds. The timing argument tends to favor a high total mass for the Milky Way plus Andromeda. But the tracer approach, when simplified into a round, “spherical” model, can point to a lower mass inside a few megaparsecs. Scientists have argued over that mismatch for years.

Simulations that match the real sky

To tackle the problem, Wempe and colleagues built simulations designed to resemble your real cosmic neighborhood. They used a Bayesian framework called Bayesian Origin Reconstruction from Galaxies, or BORG, to create many possible universes consistent with standard cosmology. Then they ran 169 higher-detail resimulations using the code Gadget-4.

Their goal was direct. They wanted a “virtual twin” of the Local Group that matches the Milky Way and Andromeda’s masses and motion, plus the positions and speeds of 31 isolated galaxies out to about 4 megaparsecs.

The simulations produced a combined halo mass of about 3.3 ± 0.6 trillion times the sun’s mass. Yet the nearby galaxies still showed a “quiet” local expansion, with modest scatter. In other words, the neighborhood can look calm even if the total mass is large.

Why do round models fail?

So why do round models fail? In a truly spherical setup, only the mass inside a given radius matters for the pull you feel. But the simulations point to a strongly flattened structure. In a sheet, matter farther out in the plane can tug outward on tracer galaxies, partly canceling the inward pull from mass nearer the center. That keeps recession speeds higher than a spherical model would predict.

Helmi said that is the long-missing bridge between galaxy motions and where matter sits. “I am excited to see that, based purely on the motions of galaxies, we can determine a mass distribution that corresponds to the positions of galaxies within and just outside the Local Group.”

The team also says the sheet lines up closely with the Local Sheet of galaxies, which is itself close to the Supergalactic Plane. Above and below, the simulations link the emptier zones to nearby void regions.

One more prediction stands out. The local flow of matter should be highly directional, with strong infall toward the sheet from above and below. That pattern is hard to confirm today because there are few known, close “high-latitude” tracer galaxies. Finding more small, isolated dwarf galaxies off the plane could provide a sharp test.

Research findings are available online in the journal Nature Astronomy.

The original story "Giant dark matter 'sheet' may shape galactic motion in the Milky Way" is published on The Brighter Side of News.

Related Stories

- Scientists build the world’s first large-scale quantum sensor network to search for dark matter

- Astronomers produce the sharpest map of dark matter in the Universe

- Scientists reveal how dark matter formed in the early universe and why its still here

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.

Joseph Shavit

Writer, Editor-At-Large and Publisher

Joseph Shavit, based in Los Angeles, is a seasoned science journalist, editor and co-founder of The Brighter Side of News, where he transforms complex discoveries into clear, engaging stories for general readers. With vast experience at major media groups like Times Mirror and Tribune, he writes with both authority and curiosity. His writing focuses on space science, planetary science, quantum mechanics, geology. Known for linking breakthroughs to real-world markets, he highlights how research transitions into products and industries that shape daily life.