Hidden Martian deltas point to an ancient ocean covering half of Mars

Orbiter cameras helped researchers map delta-like deposits in Mars’ Valles Marineris, offering strong evidence of a past ocean and a once wetter planet.

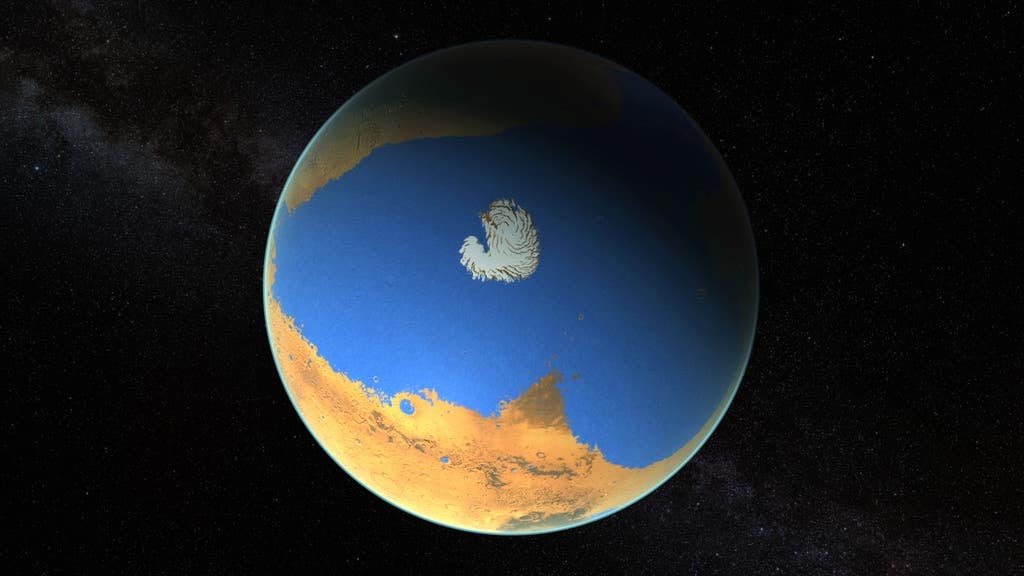

Orbiter images reveal delta-like deposits in Valles Marineris, pointing to a vast ancient Martian ocean about 3 billion years ago. (CREDIT: Scientific Visualization Studio)

Three billion years ago, you could have stood on Mars and watched a river spill into a sea. That picture is still speculative, but new evidence makes it harder to dismiss.

Researchers at the University of Bern, working with the INAF; Osservatorio Astronomico di Padova, report that they have identified landforms near Valles Marineris that closely match river deltas on Earth. The features sit near the southeast portion of Coprates Chasma, part of the planet’s largest canyon system. The team argues these deposits mark where rivers once entered a standing body of water, likely an ocean. Their study appears in the journal npj space exploration.

A coastline emerges from orbital images

You have seen Mars described as dry and red. Yet orbiters keep revealing signs of earlier water, including minerals altered by water and layered sediments that hint at lakes. Valles Marineris, a canyon chain stretching more than 4,000 kilometers, has been a major target in that search.

In this work, the Bern-led group used high-resolution images and elevation data from several instruments. Those include the Bern-built CaSSIS camera on the European Space Agency’s ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter, plus data from Mars Express and Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter. The goal was to map the shapes and heights of fan-like deposits and test whether they fit a shoreline.

“The unique high-resolution satellite images of Mars have enabled us to study the Martian landscape in great detail by surveying and mapping,” says Ignatius Argadestya, a PhD student at the Institute of Geological Sciences and the Physics Institute of the University of Bern and the study’s first author.

Nicolas Thomas, a professor in the University of Bern’s Department of Space Research and Planetary Sciences, helped lead the development of CaSSIS. “CaSSIS has been providing high-resolution color images of the surface of Mars since April 2018. The images are regularly used in scientific studies. I am personally very pleased that the images have now also been used in a geomorphological study by the Institute of Geological Sciences,” Thomas says.

What the team found in Coprates Chasma

When you look at a classic delta on Earth, you see a river delivering sediment into still water. The deposit often spreads outward like a fan, then drops sharply at the shoreline.

Argadestya says that is the pattern he noticed on Mars. “When measuring and mapping the Martian images, I was able to recognize mountains and valleys that resemble a mountainous landscape on Earth. However, I was particularly impressed by the deltas that I discovered at the edge of one of the mountains,” he says.

The team focused on scarp-fronted deposits, fan-shaped bodies that begin at the end of a valley, widen outward, and terminate at a steep front. On one well-imaged fan, the slope changes sharply at consistent elevations. The researchers place the key shoreline range between about -3,750 and -3,650 meters.

Fritz Schlunegger, a professor of exogenous geology at the University of Bern, says the geometry is the point. “Delta structures develop where rivers debouch into oceans, as we know from numerous examples on Earth,” he says. “The structures that we were able to identify in the images are clearly the mouth of a river into an ocean,” Schlunegger continues.

You also see signs of what happened after water disappeared. The fan surfaces hold desiccation cracks, later covered in places by wind-driven ripples. That sequence implies drying first, then dune activity. Today, dunes partly mask the deposits, but the fan shapes remain recognizable.

Tracing a shared water level across a wider region

If a shoreline existed, you would expect to find similar deposits at similar heights elsewhere. The researchers traced the same elevation range westward across parts of Valles Marineris toward regions that connect to the northern lowlands. They report three more sites with comparable scarp-fronted, fan-shaped deposits that fall within the same height band.

The study treats these as pieces of a broader episode, not isolated accidents. Similar landscape “building blocks” repeat across the sites: bedrock ridges dividing basins, loose slope material feeding channels, and fan-shaped deposits at valley outlets.

The team argues the deposits fit fan deltas better than dry alluvial fans later carved by erosion. In their interpretation, sediment moved from ridges into channels, then spread into standing water at the margin of a sea or large lake. The sharp break in slope marks the delta front, which formed at the water’s edge.

The researchers also infer water-level shifts of about 100 meters during that time. A higher break in slope appears near -3,650 meters, above the lower feature near -3,750 meters.

A “blue planet” claim, with a timeline

The team ties the shoreline to a period near the boundary between the Late Hesperian and the Early Amazonian, when Mars may have been wetter than it became later. The idea is that valleys and channel networks expanded during that interval, allowing rivers to cut deeper and deliver more sediment.

The study also weighs the scale of the water body. Schlunegger told the The Brighter Side of News, "Reconstruction relies on sharper evidence than earlier estimates. We are not the first to postulate the existence and size of the ocean. However, earlier claims were based on less precise data and partly on indirect arguments. Our reconstruction of the sea level, on the other hand, is based on clear evidence for such a coastline, as we were able to use high-resolution images.”

Argadestya frames the result in simple terms. “With our study, we were able to provide evidence for the deepest and largest former ocean on Mars to date – an ocean that stretched across the northern hemisphere of the planet,” he says.

You cannot confirm habitability from landforms alone. Still, deltas matter because they concentrate sediment, preserve layers, and can trap chemical traces. Argadestya also points to the broader lesson. “We know Mars as a dry, red planet. However, our results show that it was a blue planet in the past, similar to Earth. This finding also shows that water is precious on a planet and could possibly disappear at some point,” he emphasizes.

The next step, the team says, is to examine minerals linked to the old sediments. “Now that we know that Mars was a blue planet, we also want to know what kind of weathering took place there,” concludes Argadestya.

Practical Implications of the Research

You can expect this work to shape where scientists look for the best-preserved records of Mars’ watery past. Fan deltas are prime targets because they can hold fine sediments and layered deposits that lock in environmental history. By pinning down a shoreline elevation and tracing it across multiple regions, the study offers a clearer map of where water once stood and where it likely never reached.

Future missions can use these shoreline markers to choose landing sites and sampling plans. If Mars ever hosted life, deltas would be among the likeliest places to preserve chemical or textural signs of it. The findings also help researchers test climate models that try to explain how Mars could support large bodies of water, then lose them.

In a broader sense, the work adds to a comparative story you can apply to Earth, showing how planets can shift from wet to arid as conditions change.

Research findings are available online in the journal npj Space Exploration.

Related Stories

- NASA orbiter data challenges the idea that liquid water exists on Mars

- First direct evidence of how Mars lost its thick atmosphere and water

- NASA researchers discover what happened to Mars' water

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.

Joseph Shavit

Writer, Editor-At-Large and Publisher

Joseph Shavit, based in Los Angeles, is a seasoned science journalist, editor and co-founder of The Brighter Side of News, where he transforms complex discoveries into clear, engaging stories for general readers. With vast experience at major media groups like Times Mirror and Tribune, he writes with both authority and curiosity. His writing focuses on space science, planetary science, quantum mechanics, geology. Known for linking breakthroughs to real-world markets, he highlights how research transitions into products and industries that shape daily life.