JWST may have found a thick atmosphere in an unexpected place — an ultra-hot super-Earth

A new JWST study shows that TOI 561 b keeps a thick atmosphere despite extreme heat, challenging long held ideas about rocky worlds.

Edited By: Joshua Shavit

Edited By: Joshua Shavit

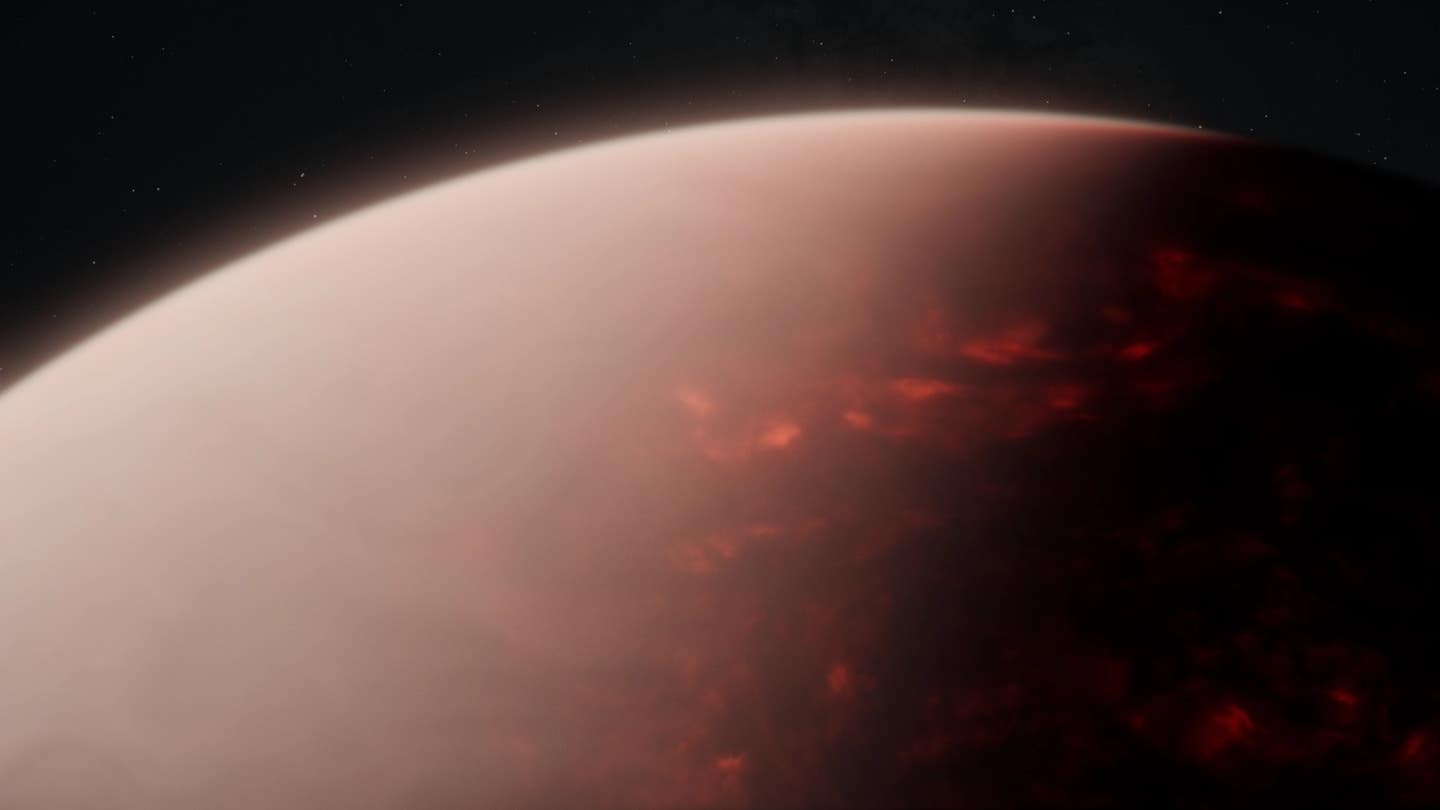

An artist’s rendering shows TOI-561 b with a thick atmosphere over a global magma ocean, supported by Webb observations indicating the planet isn’t a bare rock despite intense stellar radiation. (CREDIT: NASA, ESA, CSA, Ralf Crawford (STScI))

A tightly orbiting planet in another star system is overturning long held ideas about what small, super heated worlds can keep around them. TOI 561 b circles its star in less than half a day and faces temperatures high enough to melt rock, yet new observations from the James Webb Space Telescope show strong evidence for a dense atmosphere. The finding challenges common expectations about how extreme light and heat strip gases from planets over time.

A planet that breaks expectations

TOI 561 b is a rocky super Earth about 1.42 times the size of Earth and a little more than twice its mass. It travels so close to its parent star that a year lasts just 10.56 hours. One side stays in constant daylight. Conditions on the surface would melt rock and create what scientists call a magma ocean. The planet should be a bare molten world, yet its low density points to something more complex than a simple ball of rock and metal.

Measurements show the planet’s density is about 4.3 grams per cubic centimeter, well below what you would expect for a world of its size with an Earth like interior. That mismatch hints at a layer of gas that adds volume without adding much mass.

The surprise is that strong radiation from the host star should have removed such gases long ago. The star itself is nearly 11 billion years old and poor in iron, which means the system formed in a very different chemical environment than our solar system. That history adds another layer of mystery to how the planet has kept a thick envelope for so long.

The star’s age also makes the continued presence of an atmosphere even harder to explain. Smaller and hotter worlds in our own solar system lost their early gas layers billions of years ago. Seeing one remain on such an intense super Earth suggests that older systems may hold surprises about planetary evolution.

Tracking a faint glow with JWST

To explore TOI 561 b’s unusual nature, a team led by Carnegie Science used the James Webb Space Telescope and its NIRSpec instrument. They captured four secondary eclipses between May 1 and May 3, 2024. A secondary eclipse happens when the planet slides behind its star. The brief dip in light lets astronomers isolate the heat coming from the planet’s dayside.

JWST used a high resolution grating to gather light from 2.67 to 5.14 micrometers, a range suited for studying infrared emission. The telescope collected more than twenty thousand six second exposures during the thirty seven hour visit. Two independent data pipelines, Eureka and ExoTiC JEDI, processed the raw files. The pipelines correct for known detector behavior such as saturation, dark current and background noise.

The results from the two methods matched closely. That agreement matters because the signature of the planet is extremely faint. The change in brightness during an eclipse measures only a few dozen parts per million. Even small errors could hide or exaggerate the effect.

After extracting the spectra, the team built what are known as white light curves by adding together the flux within broader wavelength bands. They fit these curves with models that included the eclipse shape and detector trends. The eclipse depth was found to be about 25 parts per million at shorter wavelengths and about 46 parts per million at longer wavelengths. Repeating the fits across all four eclipses produced nearly identical results, which strengthened confidence in the measurements.

A cooler surface than theory predicts

The researchers divided the spectrum into seven bins and repeated the fitting to build an emission spectrum. They then compared the results with a simple blackbody curve. A blackbody fit gives a brightness temperature, which is a way of describing how hot the dayside appears based on the intensity of its infrared light.

The best estimates ranged from roughly 1800 to 2150 kelvins. Those temperatures are far below the 2950 kelvins expected for a bare surface with no atmosphere to move heat or block radiation. Even the equilibrium temperature for a planet with perfect heat circulation and no reflective clouds would be around 2310 kelvins. The planet simply emits too little infrared light to match the idea of a naked molten world.

The team also looked for signs of molecules like water vapor, carbon monoxide, carbon dioxide and silicon monoxide. A more detailed retrieval model that allowed the atmospheric composition and temperature profile to vary did not offer a better fit than the simple blackbody. The signal is small, so the available data could not resolve fine spectral features. Even so, the brightness temperature provides strong clues about the kind of environment that must exist on the planet.

The next step was to compare the results to models with real chemistry and energy transport. A very thin rock vapor layer could not reproduce the data. These models predicted higher emission and showed poor statistical fits. The team then tested thicker atmospheres rich in water or mixtures of oxygen and water. These thicker envelopes matched the data well and produced acceptable fits across the entire observed range.

A thick volatile rich envelope survives the heat

A dense volatile atmosphere would move heat from the dayside to the nightside and create strong winds. Molecules like water vapor absorb infrared light, making the dayside appear cooler to the telescope. Cloud layers made of silicate materials could also reflect light and further lower the observed temperature. These effects together paint a picture of a planet wrapped in a heavy blanket of gas that remains stable despite harsh conditions.

The idea defies the so called cosmic shoreline, an empirical trend that links atmospheric survival to a planet’s gravity and the radiation it receives. According to that trend, TOI 561 b should not have kept any significant gas. The new observations show that reality can diverge from that simple rule. For very hot rocky planets, magma oceans may act as long term sources and sinks of gases, allowing atmospheres to rebuild as fast as they escape.

Carnegie Science astronomer Johanna Teske, the lead author of the study published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters, said the data raise more questions than they answer.

Postdoctoral Fellow Nicole Wallack said, "For irradiated rocky planets with dayside temperatures above about 2000 kelvins, magma oceans may act as long-term sinks and sources of volatiles. These have allowed atmospheres of heavier gases to survive for billions of years."

Co author Anjali Piette added that wind patterns and infrared absorbing gases must shape the planet’s energy balance. Tim Lichtenberg of the University of Groningen suggested that an exchange between the magma ocean and the atmosphere may keep the gas layer stable over time.

This project used JWST’s General Observers Program 3860 and covered nearly four full orbits of the planet. The team is now analyzing the full data set to map temperatures across the surface and better identify what the atmosphere contains.

Practical applications of this research

Professor Anjali Piette summarized the study's applicability with The Brighter Side of News as follows.

"The main applications of this research are related to understanding our position in the universe, and what rocky planets can look like beyond the solar system. Although we know of rocky planets with atmospheres within the solar system, finding atmospheres on rocky exoplanets has been really challenging. Part of this is because they’re difficult to detect, but we also think that some rocky exoplanets may not have atmospheres at all, as they could be ‘blown away’ by intense radiation from their host stars. This would have implications for whether these exoplanets could be habitable, since you would likely need an atmosphere for that."

"The detection of an atmosphere on TOI-561 b is exciting because it tells us that (surprisingly!) an atmosphere has been able to survive on this highly-irradiated planet. In turn, this could mean that atmospheres could survive on other rocky exoplanets too. We don’t fully understand how TOI-561 b has kept hold of its atmosphere, so this detection will also spark new research into finding that out."

Research findings are available online in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

Related Stories

- Groundbreaking discovery sheds new light on rare 'lava planets'

- Exoplanet TRAPPIST-1e may hold Earth-like atmosphere, JWST finds

- Astronomers capture first 3D view of an exoplanet’s atmosphere and climate

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.

Joseph Shavit

Writer, Editor-At-Large and Publisher

Joseph Shavit, based in Los Angeles, is a seasoned science journalist, editor and co-founder of The Brighter Side of News, where he transforms complex discoveries into clear, engaging stories for general readers. With vast experience at major media groups like Times Mirror and Tribune, he writes with both authority and curiosity. His writing focuses on space science, planetary science, quantum mechanics, geology. Known for linking breakthroughs to real-world markets, he highlights how research transitions into products and industries that shape daily life.