Life may have begun in sticky gels long before the first cells formed

New research from Hiroshima University suggests life began in sticky gels that protected early chemistry before cells existed.

Edited By: Joseph Shavit

Edited By: Joseph Shavit

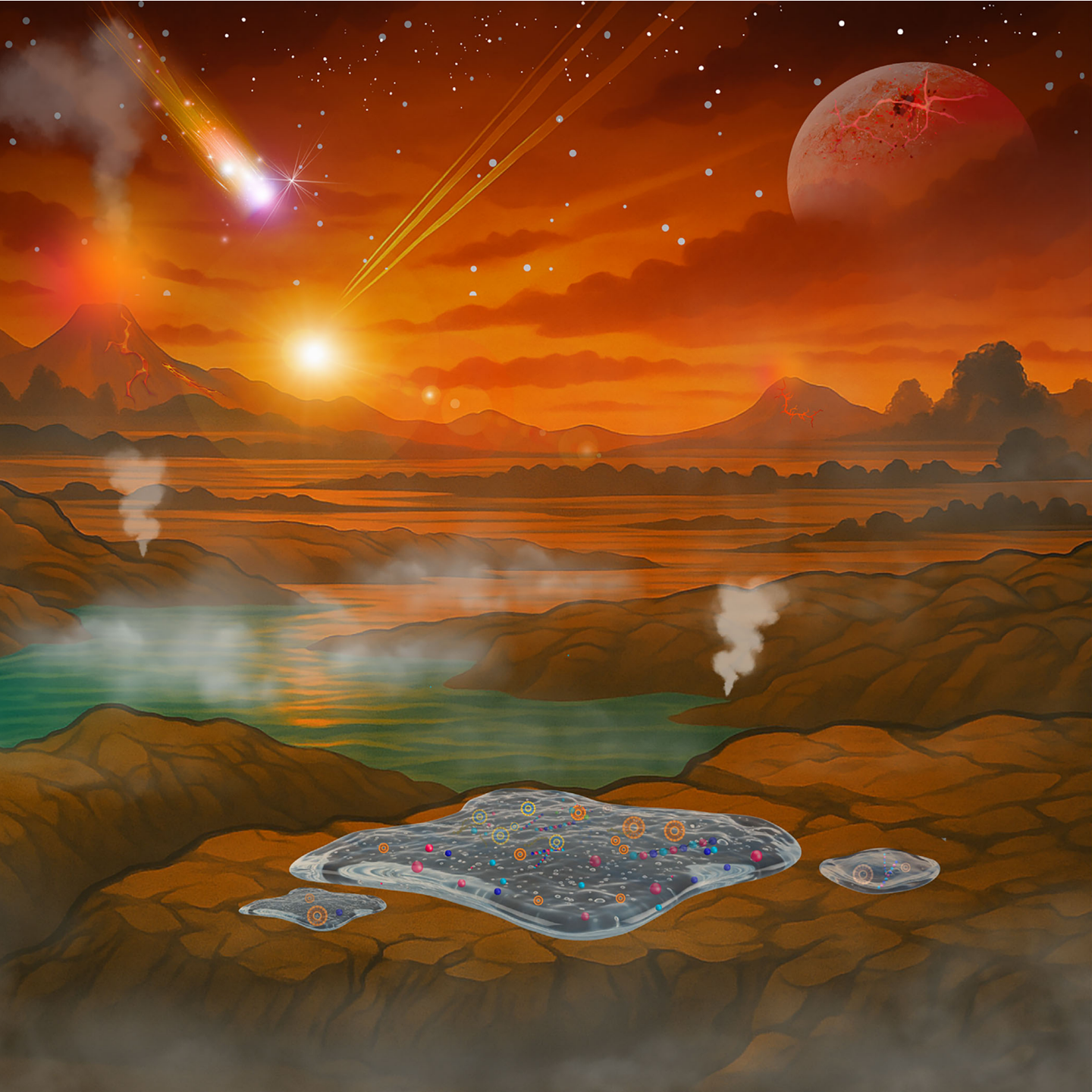

New research suggests life began in sticky gels that protected early chemistry before cells existed. (CREDIT: ChemSystemsChem)

For decades, scientists have searched for clues to how life first emerged on Earth. Many theories focus on simple molecules reacting in water or on fragile protocells drifting in ancient seas. A new study from Hiroshima University offers a different view. The earliest steps toward life may have taken place inside sticky, gel-like materials attached to Earth’s surfaces.

This idea comes from an international team of researchers who argue that these “prebiotic gels” provided protection, structure, and stability long before true cells existed. Their work suggests that life may have learned to organize and persist inside soft, surface-bound networks rather than isolated bubbles in open water.

The study, published online in the journal ChemSystemsChem, draws inspiration from modern microbial biofilms. These dense, surface-attached communities show how life benefits from sticking together, sharing resources, and buffering harsh conditions. According to the authors, similar advantages may have been essential at the dawn of biology.

Rather than treating gels as passive backdrops, the researchers describe them as active environments that helped chemistry become more complex. Within these networks, molecules could concentrate, interact repeatedly, and survive conditions that would have destroyed them elsewhere.

A Hostile Early Earth Needed Shelter

More than 3.5 billion years ago, Earth was a dangerous place for fragile chemistry. There was no ozone layer to block ultraviolet radiation. UV-C light, the most damaging form, could break apart nucleic acids, peptides, and early membranes.

Surface temperatures also fluctuated widely. Heat could sever chemical bonds needed to build larger molecules. Under such conditions, simple protocells drifting freely in water would have faced constant destruction.

Modern microbes offer a clue. Single cells often survive extreme environments by forming biofilms. These communities produce a sticky matrix called extracellular polymeric substances that traps water, binds nutrients, and shields cells from stress.

The authors argue that early Earth chemistry likely needed similar support. A gel-like platform could have provided protection, concentrated materials, and allowed chemical systems to persist long enough to evolve.

How Gels Could Drive Early Chemistry

Prebiotic gels are semi-solid networks made from polymers, peptides, clays, or other simple compounds. These materials can trap water and dissolved chemicals, creating a structured environment rather than a diluted soup.

One major benefit is confinement. Inside a gel, molecules remain close together and collide more often. This increases the chances of chemical reactions occurring. Experiments cited in the study show that hydrogels can speed up reactions by clustering reactive groups.

In one example, an imidazole-based gel enhanced ester hydrolysis by holding catalytic molecules in close proximity. In another, clay hydrogels concentrated nucleic acids and boosted protein production in cell-free systems.

Crowding inside gels also slows diffusion. Even small molecules move several times slower than they do in water. This reduced movement allows chemicals to build up locally, forming reaction-rich pockets.

These features address a long-standing challenge in origin-of-life research: dilution. In open water, important molecules often spread too thin to interact efficiently. Gels solve this problem naturally.

Selective and Active Chemical Spaces

Gels are not chemically neutral. Their pore size and composition allow them to act as selective filters. Some retain large molecules, while others bind charged or structured compounds.

Clay minerals, for example, can attract positively charged amino acids and help organize RNA strands. Other gels absorb metal ions such as calcium, magnesium, and iron, which play key roles in many prebiotic reactions.

The study also highlights a process called dynamic mechanical loading. Environmental forces like waves or wet-dry cycles can push solutes deeper into a gel, even against concentration gradients. This behavior resembles a simple form of active transport.

Water behavior inside gels matters as well. Much of the water is bound to the network, lowering its activity. Reduced water activity favors condensation reactions, including peptide and ester formation.

Some gels form protective outer layers as they dry, trapping moisture inside. Deliquescent salts within gels can even pull water from the air, maintaining hydration under dry conditions.

Shielding Fragile Chemistry

Protection from radiation and heat may have been critical. Mineral-rich gels containing montmorillonite clay can block more than 90 percent of UV-C radiation when only a millimeter thick.

Organic gels enriched with polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, which are common in meteorites, also absorb harmful ultraviolet light. This shielding could have preserved delicate molecules during long exposure.

Thermal stability adds another advantage. Silica-based hydrogels can withstand high temperatures without breaking down. Many clays hold water layers bound to metal ions, increasing resistance to heat.

Gels may also buffer sudden changes in acidity. Early Earth experienced frequent pH swings due to volcanic gases and rock weathering. Polymer-based gels with ionizable groups can resist these shifts. Phosphate and borate compounds may have provided additional buffering.

Toward Metabolism and Replication

Once gels created stable microenvironments, they may have supported early metabolism. Redox-active molecules and metals inside gels could move electrons and drive energy-demanding reactions.

The authors also describe chemomechanical coupling. Some gels swell and shrink in response to internal chemical cycles. Oscillating reactions can cause rhythmic expansion and contraction.

These movements may have helped draw in nutrients and expel waste. Such behavior resembles basic functions seen in living systems today.

Internal cycling could also support autocatalytic networks, where molecules help produce more of themselves. This self-reinforcing chemistry may have pushed systems toward life-like behavior.

From Gels to the First Cells

The study outlines several paths from gels to true cells. Gels could have produced tiny droplets through phase separation. These droplets might later acquire membranes and become protocells.

In other cases, membrane-forming molecules may have assembled vesicles directly inside the gel. These structures could eventually detach and survive independently.

In every scenario, gels were active participants. They gathered ingredients, protected fragile chemistry, and guided the transition from nonliving matter to biology.

"Redox-active molecules and metals inside gels could have helped move electrons and power energy-demanding reactions such as forming amino acids, thioesters, or energy-rich molecules like pyrophosphate," Kuhan Chandru, a research scientist at the Space Science Center at the National University of Malaysia and co-lead author told The Brighter Side of News.

“This is just one theory among many in the vast landscape of origin-of-life research,” Chandru continued. “However, since the role of gels has been largely overlooked, we wanted to synthesize scattered studies into a cohesive narrative.”

Broader Implications for Life Beyond Earth

The researchers extend their ideas to astrobiology. Similar gel-like systems could exist on other planets, even if their chemistry differs from Earth’s.

These potential “Xeno-films” may serve as non-terrestrial counterparts to biofilms. Instead of searching only for familiar molecules, scientists might look for structured, surface-bound systems.

“While many theories focus on the function of biomolecules and biopolymers, our theory instead incorporates the role of gels at the origins of life,” said Tony Z. Jia, a professor at Hiroshima University and co-lead author.

Future experiments will test whether simple gels can form under early Earth conditions and how they influence chemical behavior. The team hopes their work encourages further exploration of overlooked pathways.

“We also hope that our work inspires others in the field,” said Ramona Khanum, co-first author and a former intern at the National University of Malaysia.

Research findings are available online in the journal ChemSystemsChem.

Related Stories

- New scientific discovery reveals the origin of life on Earth

- Microlightning in water droplets may have ignited life on Earth

- Scientists discover how life on Earth began 1.75 billion years ago

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.

Rebecca Shavit

Writer

Based in Los Angeles, Rebecca Shavit is a dedicated science and technology journalist who writes for The Brighter Side of News, an online publication committed to highlighting positive and transformative stories from around the world. Her reporting spans a wide range of topics, from cutting-edge medical breakthroughs to historical discoveries and innovations. With a keen ability to translate complex concepts into engaging and accessible stories, she makes science and innovation relatable to a broad audience.