Metabolites preserved in fossil bones reveal ancient diets, diseases, and habitats

Scientists extract metabolic molecules from fossil bones to reveal ancient diets, disease, and environments millions of years old.

Edited By: Joshua Shavit

Edited By: Joshua Shavit

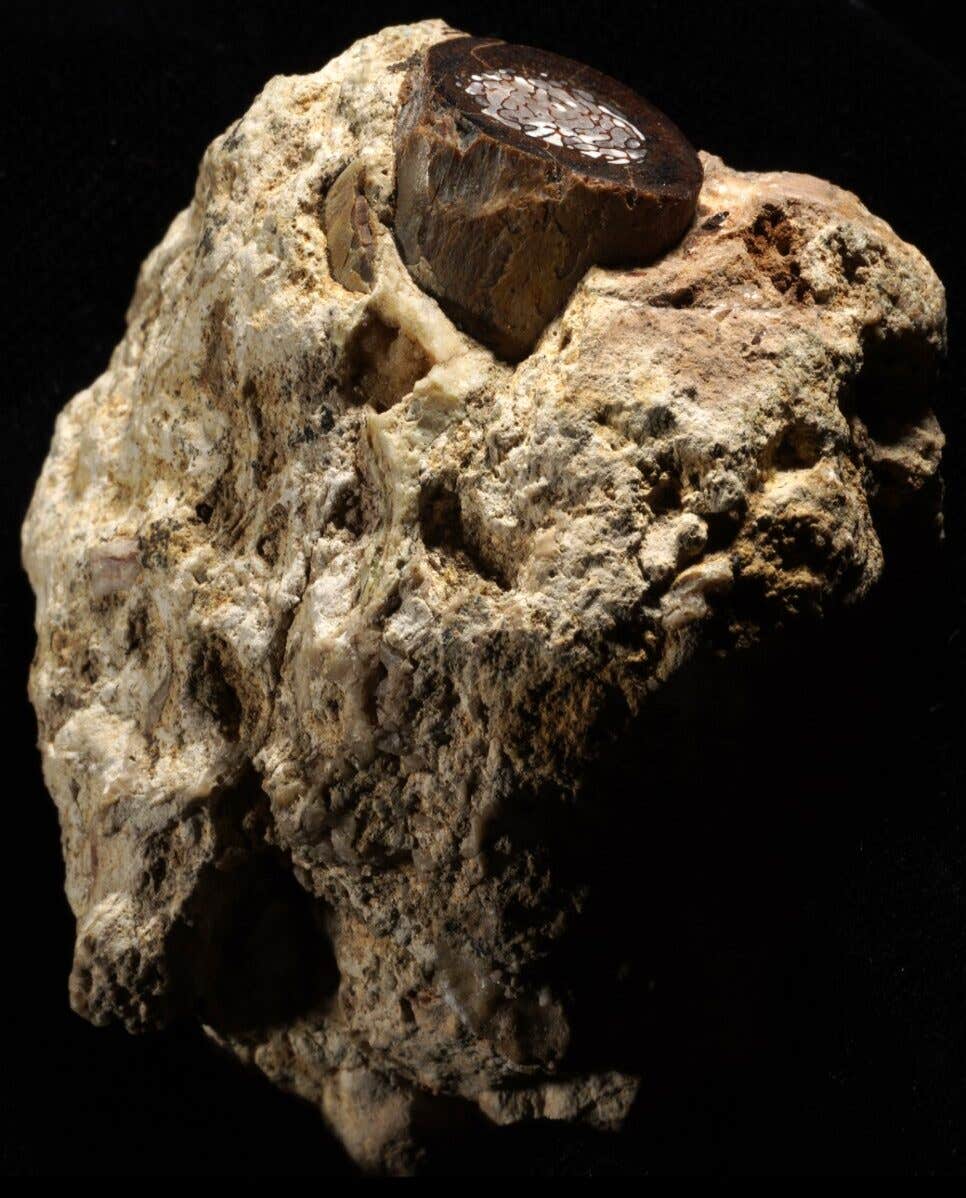

Antelope bone fragment in rock from the 3-million-year-old early human site, Makapansgaat (South Africa). (CREDIT: Timothy Bromage and Bin Hu, NYU Dentistry)

Metabolism quietly governs every living body. It shapes how organisms grow, reproduce, heal, and age. Because metabolism links closely to body size, temperature, and diet, it also sets limits on how animals interact with their environments. If traces of that metabolic activity survive in fossils, they can reveal how extinct animals lived and the worlds they once occupied.

Researchers from New York University, working with international collaborators, now report that such traces do survive. Led by Timothy Bromage, a professor of molecular pathobiology at NYU College of Dentistry and an affiliated professor in NYU’s Department of Anthropology, the team analyzed metabolism-related molecules preserved in fossil bones dating back 1.3 to 3 million years.

The study introduces a new approach called palaeometabolomics. Instead of relying only on bone structure, isotopes, or surrounding sediments, this method examines small molecules known as metabolites that once circulated through an animal’s bloodstream.

“I’ve always had an interest in metabolism, including the metabolic rate of bone, and wanted to know if it would be possible to apply metabolomics to fossils to study early life. It turns out that bone, including fossilized bone, is filled with metabolites,” Bromage said.

How chemistry survives inside bone

Modern metabolomics usually relies on blood, urine, or saliva. Fossils offer none of those. Bromage and his colleagues suspected that metabolites could become trapped inside bone during growth. Bone tissue contains tiny spaces where blood vessels exchange nutrients. As bone mineralizes, molecules from the bloodstream can seep into microscopic niches and remain sealed.

“I thought, if collagen is preserved in a fossil bone, then maybe other biomolecules are protected in the bone microenvironment as well,” Bromage said.

To test this idea, the team first examined fossil bone structure using microscopy and chemical mapping. Rodent fossils from Olduvai Gorge in Tanzania, an elephant from the Chiwondo Beds in Malawi, and a bovid from Makapansgat in South Africa all showed preserved internal patterns consistent with surviving collagen.

Protein analysis confirmed peptides linked to bone collagen in several fossils. Some samples also carried peptides associated with parasitic infection. Chemical tests showed that fossil bones retained their basic mineral identity, even after absorbing calcium from surrounding soils.

Together, these results supported a critical idea. Fossil bones still preserve protected chemical environments capable of holding original metabolic signals.

Testing the method with living animals

"Before turning fully to fossils, our team tested whether bone chemistry reflects diet in living animals. We analyzed long bones from laboratory mice and compared them to the food the mice ate. In one experiment, nearly half of the metabolites found in the diet also appeared in the bones," Bromage shared with The Brighter Side of News.

"A second experiment traced bone metabolites back to five specific ingredients in commercial rodent food. While the diets were artificial, the overlap showed us that bone chemistry records what animals consume over time," he continued.

The team also tested how digestion alters metabolite survival. Fossil rodents from Olduvai were likely deposited by owls. When researchers compared modern rodent bones from owl pellets to bones from live-caught animals, the pellet samples shared far fewer metabolites with fossils. Enzyme treatments in the lab produced similar losses.

These tests showed that digestive enzymes remove metabolites rather than introduce them, strengthening confidence that fossil signals reflect life, not decay.

Fossils as chemical records of health and habitat

The researchers then analyzed fossils from Tanzania, Malawi, and South Africa, focusing on species with modern relatives still living nearby. These included rodents, a pig, an antelope, and an elephant. Thousands of metabolites were recovered, many shared with living counterparts.

Metabolites made by the animals themselves showed strong overlap between fossils and modern bones. Diet and environment-related metabolites overlapped less, but still carried clear signals. Even fossils millions of years old retained recognizable metabolic fingerprints.

Soil contamination posed less of a problem than expected. Fossil bones and local soils shared similar metabolite percentages as modern bones and the same soils. This pattern suggests soils collect blended chemical signals from many organisms over time, while bones preserve individual histories.

Statistical analyses separated fossils, soils, and modern samples into distinct groups. Many metabolites linked to amino acids, energy production, vitamins, hormones, and cell growth appeared in both ancient and living animals.

Several hormone-related metabolites suggested biological sex. Evidence tied to estrogen pathways indicated that some Olduvai rodents and the Makapansgat bovid were likely female.

Disease and environment written in molecules

One of the most striking findings involved disease. Metabolites linked to Trypanosoma brucei, the parasite that causes sleeping sickness in humans, appeared in fossils from Olduvai, Chiwondo, and Makapansgat. Protein evidence supported infection in a 1.8-million-year-old ground squirrel.

“What we discovered in the bone of the squirrel is a metabolite that is unique to the biology of that parasite, which releases the metabolite into the bloodstream of its host. We also saw the squirrel’s metabolomic anti-inflammatory response, presumably due to the parasite,” Bromage said.

Plant-derived metabolites also helped reconstruct ancient habitats. Signals pointed to aloe and asparagus species that favor warm, well-drained soils, along with woody plants associated with moist woodlands. Fungal and bacterial metabolites suggested humid conditions with decaying vegetation.

“What that means is that, in the case of the squirrel, it nibbled on aloe and took those metabolites into its own bloodstream,” Bromage said. “Because the environmental conditions of aloe are very specific, we now know more about the temperature, rainfall, soil conditions, and tree canopy.”

These molecular clues align with earlier reconstructions but add detail. Olduvai Gorge appears wetter and more wooded than today, with mixed grasslands, freshwater woodlands, and marshes. Similar patterns emerged for Malawi and South Africa.

“Using metabolic analyses to study fossils may enable us to reconstruct the environment of the prehistoric world with a new level of detail, as though we were field ecologists in a natural environment today,” Bromage said.

Research findings are available online in the journal Nature.

Related Stories

- Mosasaur tooth fossil reveals giant sea reptiles lived in freshwater rivers

- Fossil tracks in Italy record a turtle stampede from 80 million years ago

- Dinosaur eggshells are accurate timekeepers of fossil age, study finds

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.

Joseph Shavit

Writer, Editor-At-Large and Publisher

Joseph Shavit, based in Los Angeles, is a seasoned science journalist, editor and co-founder of The Brighter Side of News, where he transforms complex discoveries into clear, engaging stories for general readers. With vast experience at major media groups like Times Mirror and Tribune, he writes with both authority and curiosity. His writing focuses on space science, planetary science, quantum mechanics, geology. Known for linking breakthroughs to real-world markets, he highlights how research transitions into products and industries that shape daily life.