New gravitational lens measurements reveal a faster expansion rate for the universe

New gravitational lensing research suggests the universe expands faster than early-universe models predict.

Edited By: Joseph Shavit

Edited By: Joseph Shavit

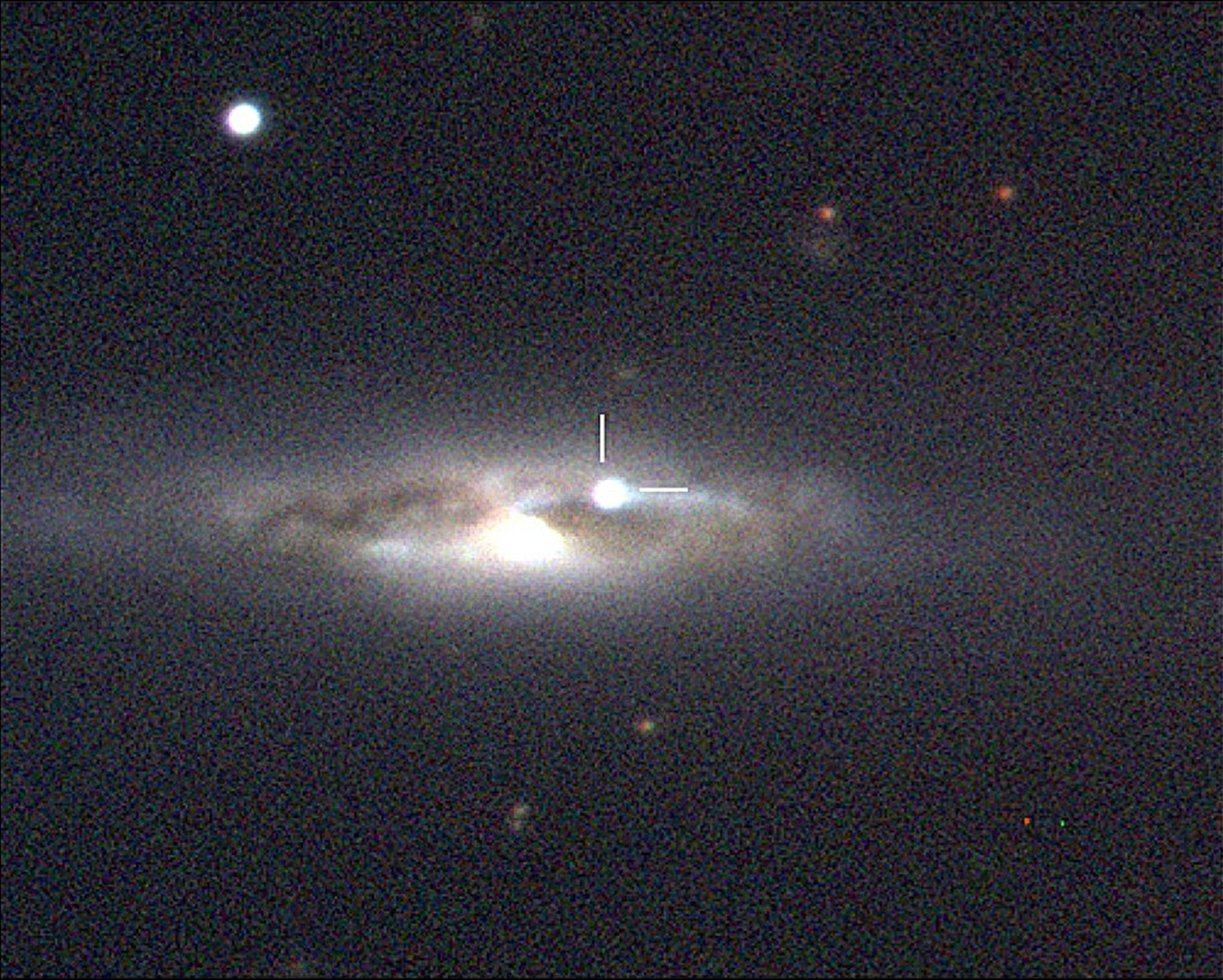

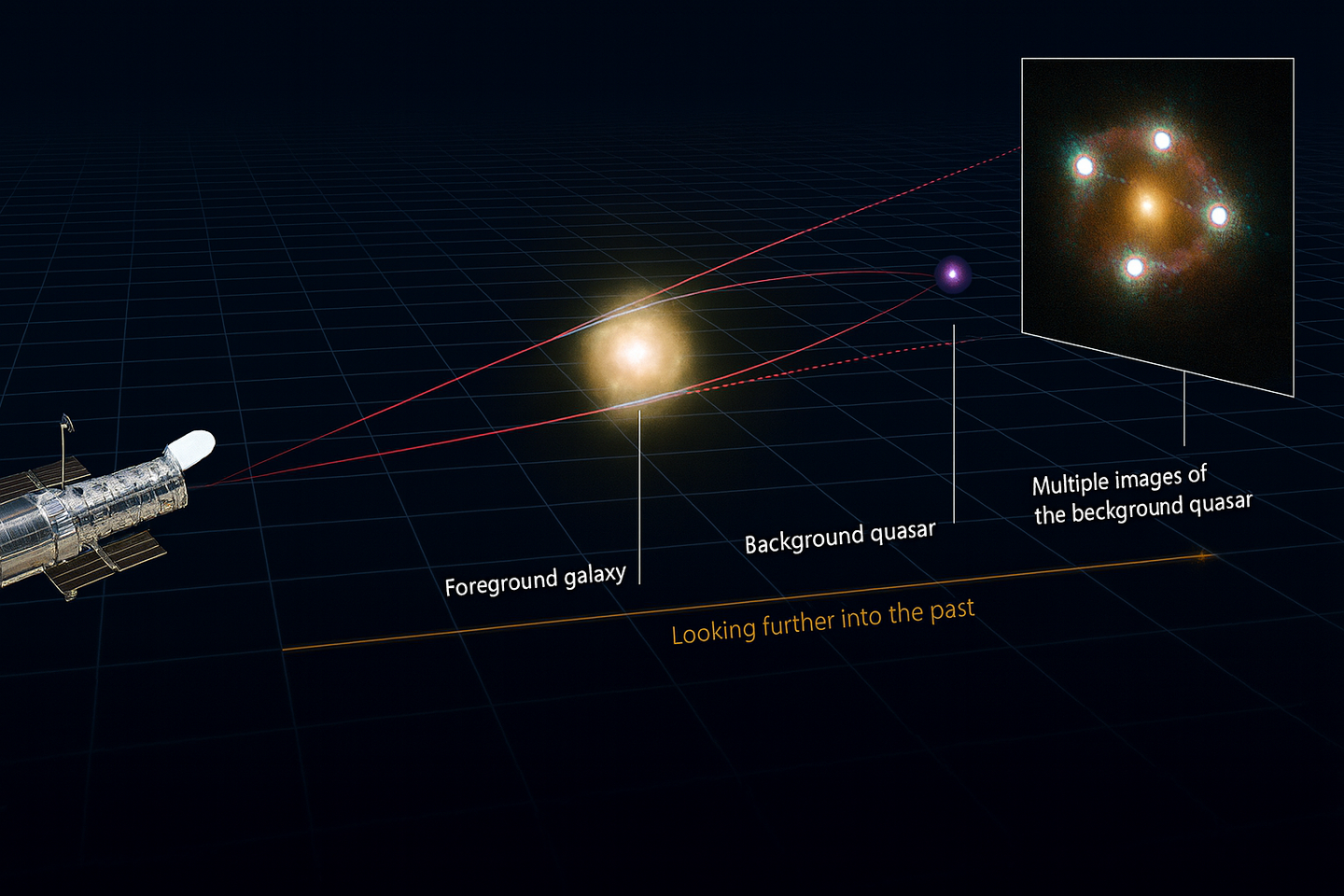

A new look at distant quasars split by gravity shows the universe may be growing faster than expected. (CREDIT: SpringerNature Link)

For much of the twentieth century, scientists expected the expanding universe to slow over time. The opposite turned out to be true. Space is stretching faster today than in the past, and the precise rate of this growth remains one of astronomy’s most debated questions.

That number, called the Hubble constant, affects estimates of the universe’s age and shapes models of how galaxies formed. Getting it wrong shifts nearly every part of cosmic history, which is why the field has spent the last decade locked in a puzzle known as the Hubble tension.

Conflicting Clues From the Early and Late Universe

Measurements from the earliest observable light, the cosmic microwave background, show the universe expanding at about 67 kilometers per second for every megaparsec of distance. Studies of nearby exploding stars and special brightening stars called Cepheids support a faster value near 73. The difference is only a few kilometers per second, but it is far larger than can be explained by chance. It raises the possibility that something about the universe has been overlooked.

Two recent efforts seek to break the deadlock by using gravity itself as the measuring tool. These projects draw on a growing collection of unusually aligned galaxies and far-off quasars. When a massive galaxy sits in front of a bright, distant object, its gravity bends the light and creates multiple images.

Each image follows a slightly different route through space and arrives at a slightly different time. Tracking those delays provides enough information to estimate distance, and therefore the expansion rate, in a way that avoids the traditional distance ladder.

How Time Becomes a Ruler

This method, called time-delay cosmography, relies on precise measurements of how long the multiple images of a quasar take to reach Earth. Because each pathway is shaped by the mass of the lensing galaxy, researchers must know how that mass is arranged. That has been the largest obstacle in past studies. Different assumptions about the mix of stars and dark matter inside a galaxy can lead to models that fit the same images but give different expansion rates.

To address this issue, the TDCOSMO collaboration gathered stellar motion data from some of the most advanced telescopes available. They used the James Webb Space Telescope’s NIRSpec instrument to map six galaxies, the MUSE instrument in Chile to observe two others, and even added detailed measurements from Keck Observatory in Hawaii for a well-known system called RX J1131−1231.

The data shows how stars move inside each lensing galaxy, which reveals the true strength of the galaxy’s gravity. With that information, the mass models become more reliable and help reduce a key source of uncertainty.

A Larger and Sharper Sample

The core of the study analyzed eight quasar-lens systems called the TDCOSMO-2025 sample. Each one involves a distant quasar split into multiple images by a galaxy that sits in front of it. The team then added two other groups of galaxies, known as SLACS and SL2S, which do not have measured time delays but do have strong gravitational lensing and high-quality data on how their stars move. In total, the sample included 23 galaxies once the researchers applied strict quality requirements.

Combining these systems gives a clearer picture of what the average lensing galaxy looks like. This reduces uncertainty in the mass models and strengthens the final measurement of the Hubble constant. The clarity from Webb and other observatories also improved by more than tenfold compared to earlier surveys, offering the most precise images yet used for this approach.

What the New Numbers Reveal

When the team from the University of Tokyo used only the eight time-delay systems, they calculated a Hubble constant of about 73.7 kilometers per second per megaparsec. Adding the SLACS and SL2S galaxies increased the estimate to roughly 77.8. To sharpen the result further, they combined their findings with major surveys of exploding stars and large collections of galaxies.

The Pantheon+ supernova dataset led to a combined value of 74.3, while a similar approach using data from the Dark Energy Survey gave 73.9. Using DESI galaxy results, the number rose to 74.8, and the group even measured a key distance scale in cosmology called the cosmic sound horizon without relying on early-universe models.

Every one of these results points higher than the value from the cosmic microwave background. They also match other recent studies of the present-day universe. The consistency suggests that the Hubble tension is not a minor statistical oddity. It may instead signal a missing part of our understanding of the cosmos.

A Growing Case for New Physics

The TDCOSMO team tested alternate cosmology models to see whether changes in the shape of space or changes in the behavior of dark energy could fix the disagreement. None of these models brought early-universe and late-universe values into full agreement. Instead, the lensing results continued to favor faster expansion.

Researchers from the University of Tokyo, including Kenneth Wong and Eric Paic, carried out a complementary study published in Astronomy & Astrophysics. Their analysis also used time-delay cosmography and drew from many of the same lensing systems.

Wong explained that their method provided a measurement “well within the ranges supported by other modes of estimation” that rely on nearby objects. Their result matched late-universe measurements and disagreed with the early-universe estimate, which supports the idea that the tension might come from real physics instead of measurement errors.

Paic noted that the team’s current precision is about 4.5 percent. Reaching a precision near one percent would allow scientists to determine whether the tension truly reflects a gap in current theory. Both researchers plan to expand their sample by adding new lensing systems and improving the mapping of stellar motions. These steps could help confirm whether something about the early universe behaves differently than expected.

Looking to the Future

The latest findings show that gravitational lensing offers one of the strongest and most independent checks of the Hubble constant. With each improvement in image quality and stellar motion data, the results point to the same answer.

The universe appears to be expanding faster than the cosmic microwave background predicts. If verified, the tension could mark the first clear sign of new physics since the discovery of dark energy.

Research findings are available online in the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics.

Related Stories

- Earth may lie in a gigantic void that skews our view of the expanding universe

- Universal expansion may be slowing down rather than speeding up

- Dark energy may have caused the universe to expand rather than contract

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.

Joshua Shavit

Writer and Editor

Joshua Shavit is a Nor Cal-based science and technology writer with a passion for exploring the breakthroughs shaping the future. As a co-founder of The Brighter Side of News, he focuses on positive and transformative advancements in technology, physics, engineering, robotics and astronomy. Joshua's work highlights the innovators behind the ideas, bringing readers closer to the people driving progress.