Newly named Canadian sea monster reveals surprising mix of traits

Traskasaura sandrae fossil shows a rare mix of traits in a marine reptile from Vancouver Island, now BC’s official fossil.

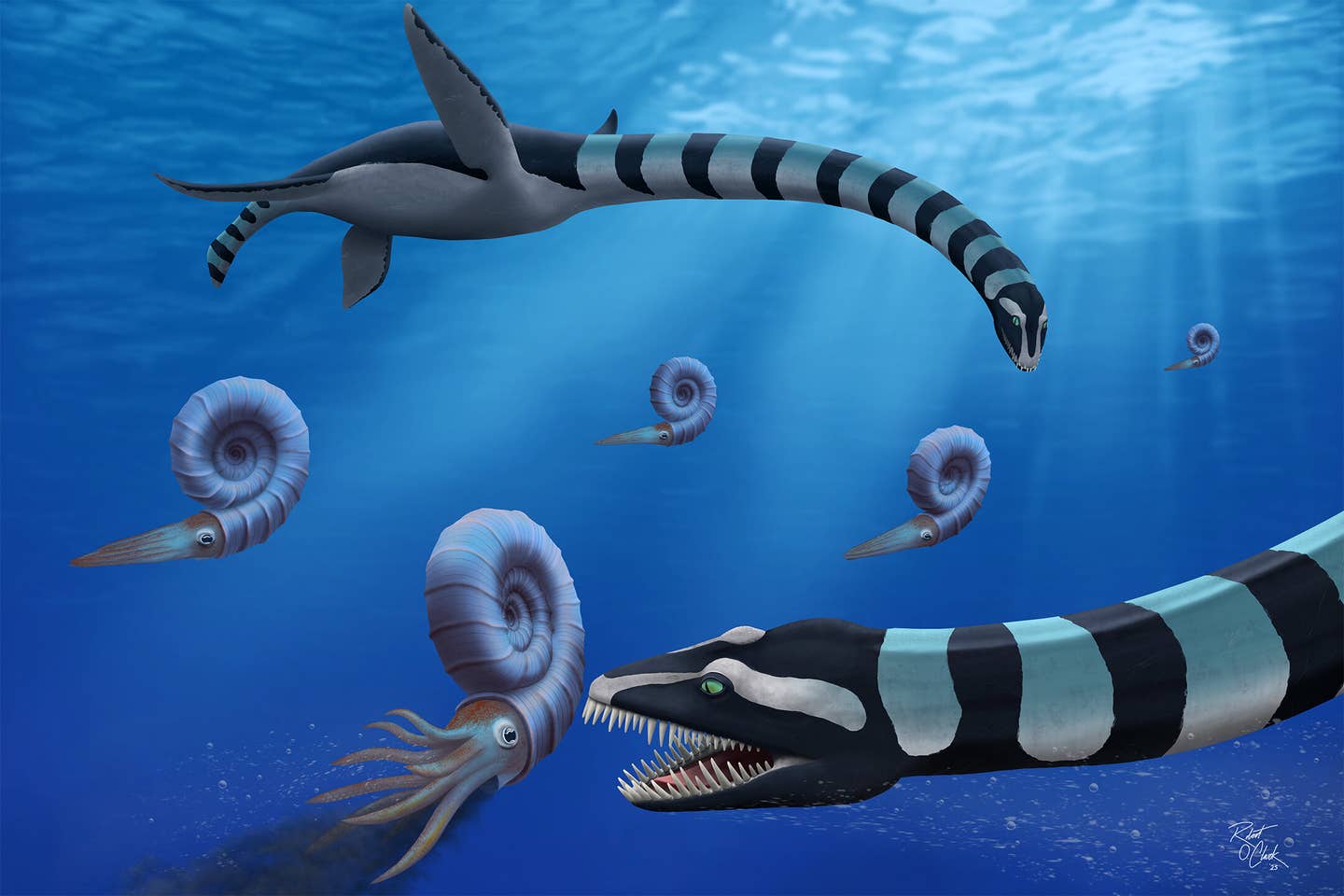

In the northern Pacific during the Late Cretaceous, two Traskasaura sandrae stalk a Pachydiscus ammonite, their prey.(CREDIT: Robert O. Clark)

A strange, long-necked marine predator from the age of dinosaurs has finally received its name, after more than 20 years of study. What started as a puzzle of ancient bones collected along the Puntledge River on Vancouver Island has turned into a story of scientific detective work, public excitement, and a big step forward in paleontology.

A fossil mystery finally gets a name

Back in 1988, Michael Trask and his daughter Heather discovered an unusual set of fossilized bones buried in the Late Cretaceous rocks of Vancouver Island. This area, part of the Haslam Formation, is known for preserving life from 85 million years ago. In 2002, researchers first described the fossils, identifying them as belonging to an elasmosaur—a type of long-necked marine reptile.

But there was a problem. The skeleton, though complete, was in poor condition. It didn’t show enough clear features to confidently assign it to a genus. Adding to the challenge was the early state of elasmosaur classification at the time. With limited data and no similar examples to compare, scientists had to wait.

That wait is over. Thanks to newly discovered fossils and better methods for analyzing prehistoric animals, paleontologists have now given the creature a name: Traskasaura sandrae. The name honors Michael and Heather Trask for their discovery, and Sandra Lee O’Keefe, remembered for her strength during a battle with breast cancer.

More fossils, more clarity

Since that first discovery, two more fossils of the same animal have been found. One is an isolated right humerus. The other is a remarkably well-preserved skeleton of a juvenile. These new finds provided the missing pieces needed to fully understand the animal’s structure.

With clearer bones and advanced techniques, scientists carried out a full phylogenetic analysis. This type of study examines how species are related through evolution. The research was published in the Journal of Systematic Palaeontology and led by Professor F. Robin O’Keefe of Marshall University, an expert in marine reptiles.

Related Stories

The results showed that Traskasaura sandrae is not just another elasmosaur. It has a strange blend of traits—some primitive, others advanced. That’s what made it so hard to classify in the first place.

“This taxon has a very odd mix of primitive and derived traits,” said Professor O’Keefe. “The shoulder, in particular, is unlike any other plesiosaur I have ever seen, and I have seen a few.”

A creature built for attack

The skeleton of Traskasaura tells the story of a powerful predator. It measured about 12 meters long, with a long neck made up of at least 36 preserved cervical vertebrae. The total number was probably over 50.

The neck vertebrae were long and narrow—what paleontologists call “plesiomorphic,” or primitive. This is a trait shared with older species like Libonectes. However, the forward-facing cervical ribs, normally seen only in more advanced elasmosaurids like aristonectines and Vegasaurus, give it a more evolved appearance.

The skull and jaw show more surprises. The mandible was narrow and armed with large, heavy teeth—perfect for crunching hard prey. That likely included ammonites, the coiled-shelled cephalopods that were common in the ancient seas around Vancouver Island.

But the most unique features were found in the bones of the limbs and chest. The coracoid, part of the shoulder, had a shape not seen in any other elasmosaur. It lacked a deep recess, but had similarities to the advanced Aristonectes quiriquinensis. The humerus bone also stood out, with a straight shaft, strong curve on the underside, and a joint surface forming a perfect right angle.

These parts of the body—what scientists call postcranial—are thought to have evolved separately from similar features in more derived elasmosaurs. This process, called convergent evolution, happens when different species evolve similar traits due to similar environments or behaviors.

In short, Traskasaura looked like no other elasmosaur. Its primitive neck and skull, combined with advanced shoulders and limbs, make it a true mosaic of ancient design.

A predator from above

One of the most exciting parts of the new study is what it says about how Traskasaura may have hunted. Professor O’Keefe believes its unusual body shape allowed it to swim downward with power and control. This might have let it attack prey from above—a rare hunting style among plesiosaurs.

Its long neck, strong shoulders, and sharp teeth paint the picture of a predator that dove through the water and snatched hard-shelled animals like ammonites. The fossil record in the area shows that these prey animals were plentiful at the time.

Though only three individuals have been studied so far, each shows key traits of the new species. Researchers note that these fossils likely all represent the same genus, and probably the same species. Still, there may be more surprises as new fossils are discovered.

From unknown bones to a provincial symbol

Beyond the science, this discovery has captured public interest. In 2023, the fossil was named the official fossil emblem of British Columbia. This came after a five-year campaign by local fossil fans and a public poll in 2018, where it earned 48% of the vote.

The bones are now on display at the Courtenay and District Museum and Palaeontology Centre. For the people of Vancouver Island, Traskasaura sandrae is more than just a prehistoric reptile. It’s a symbol of local history, scientific discovery, and the beauty of life’s long story written in stone.

Professor O’Keefe summed it up best: “With the naming of Traskasaura sandrae, the Pacific Northwest finally has a Mesozoic reptile to call its own. Fittingly, a region known for its rich marine life today was host to strange and wonderful marine reptiles in the Age of Dinosaurs.”

His colleague Rodrigo Otero, from Chile, helped confirm the creature’s unique identity. Together, the team’s work reveals how a handful of fossils can change what we know about Earth’s ancient oceans.

When science and curiosity come together, even bones buried for 85 million years can speak.

Note: The article above provided above by The Brighter Side of News.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.