Rethinking the “Ice Giants”: Uranus and Neptune may be rockier than we thought

New models reveal Uranus and Neptune may be more rocky than icy, challenging decades-old ideas about planet formation.

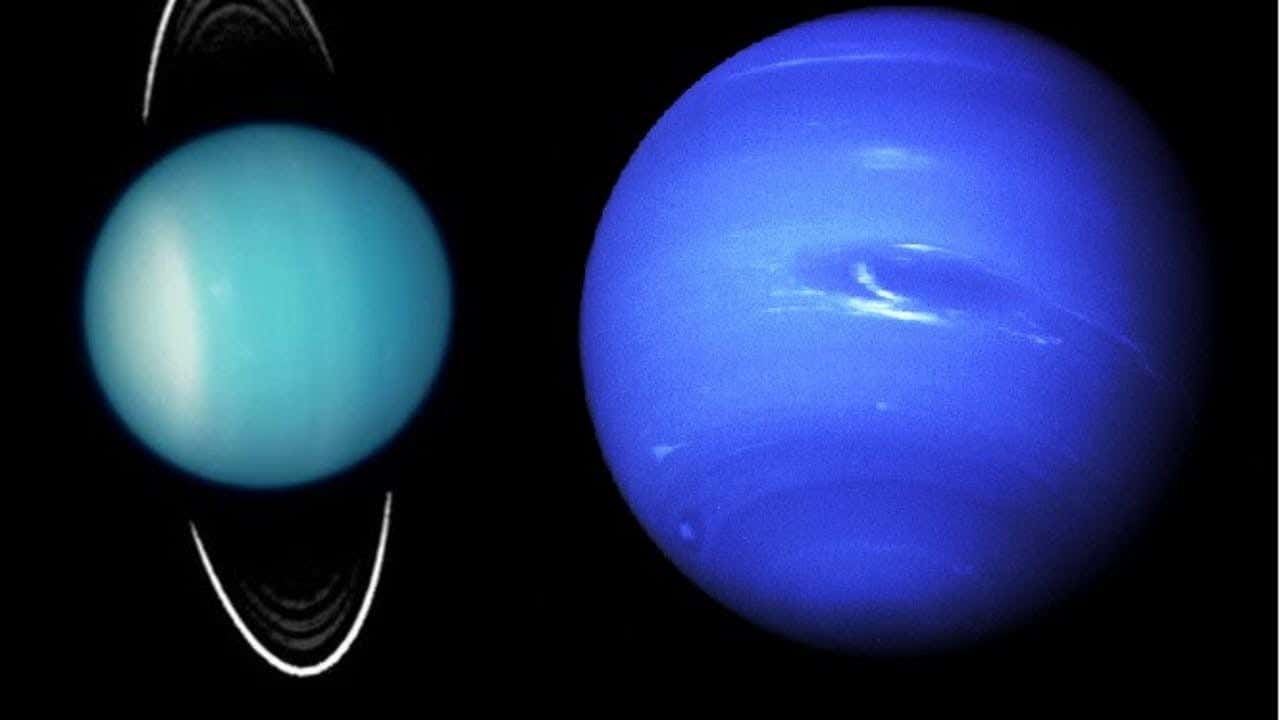

A new modeling study challenges Uranus and Neptune’s “ice giant” label. (CREDIT: FLICKR / Wikimedia Commons)

Uranus and Neptune have been called the "ice giants" for decades. But in new research, that nickname might be more a misnomer than anything.

A study by the lead researchers astrophysicists Luca Morf and Ravit Helled at the University of Zürich indicates that the faraway planets might be a lot rockier than scientists thought before, upending long-held theories about planet formation and evolution.

A New Glimpse Inside the Faraway Giants

The findings are derived from an innovative modeling strategy that balances physical rigor with flexibility. In the past, scientists built models of planetary interiors based on hard assumptions about layers of rock, ice, and gas. Morf and Helled's approach, however, starts with randomly chosen density profiles and then uses an iterative scheme to find stable solutions meeting three criteria: hydrostatic equilibrium, consistency with inferred gravitational information, and adherence to physical and thermodynamic constraints.

This "agnostic" approach produces an entire spectrum of possible interiors for Uranus and Neptune—ranging from water-enriched to rocky types. It doesn't force the planets into a definition but instead presents various possibilities that agree with what astronomers already know.

The Surprising Mix Beneath the Clouds

The new models paint a far more detailed picture of the composition of both planets. Uranus, for instance, could have anywhere from 0.04 to 3.92 rock-to-water ratio. That is, it could be almost entirely water—or rock. Neptune, by contrast, shows ratios of 0.20 and 1.78, and implies an interior that may be more rocky than watery.

These findings suggest that Uranus and Neptune can have vast regions of "ionic water," a highly conductive fluid that is formed under pressure and heat. These regions are beyond the "demixing curve," the boundary beyond which hydrogen, helium, and water would demix into distinct layers. Because these layers would likely remain in contact, their magnetic fields—already the strangest in the solar system—become even less unusual.

Uranus's outer convective zone appears to contain more hydrogen and helium than Neptune's, which could be the reason behind its weaker heat production and unusual magnetic field. Neptune, however, radiates much more energy than it receives from the Sun, a clue that it may be more efficient at transporting interior heat to its surface.

The Mystery of Magnetic Fields

One of the biggest mysteries surrounding Uranus and Neptune was always their magnetic fields, which are wild tilted and offset from their centers. For the Earth, the magnetic field is oriented roughly the same way as the planet's axis of rotation. Not for these distant worlds.

On the Zürich models, Uranus's magnetic dynamo—the region where magnetic fields are produced—is more interior to the planet, starting at about 70 percent of its radius. Neptune's extends right out to 90 percent of its radius. This is likely causing Neptune's magnetic field surge to fluctuate more erratically and sometimes appear stronger.

The presence of electrically conductive ionic water and hydrogen-helium mixtures within the interior of the planets is the cause of these fields, supporting earlier studies but with better-defined and self-consistent physics to support them.

Why These Twins Are Not Similar

While often lumped together, Uranus and Neptune are relatively dissimilar in heat, magnetism, and composition. Uranus emits much less than it receives from the Sun, while Neptune shines with an internal light of excess heat. The Zürich scientists found that the core of Uranus must contain dense composition gradients—protections which suppress convection and trap heat. Neptune's interior is more uniform, and energy can move more freely out of it.

The researchers also highlight Uranus appears relatively rock-poor while Neptune is richer in rocky material. That disparity could suggest that the two worlds evolved under very dissimilar conditions, or perhaps experienced catastrophic collisions in their early history.

Reinterpreting the "Ice Giant" Term

With the new data, "ice giant" is perhaps less a scientific truth and more an item of history. The models illustrate that all kinds of rock, water, and gas compositions are possible to account for the same gravitational and magnetic observations. The ambiguity in this makes it hard to determine which model is correct until new data arrives.

Since the 1980s Voyager 2 flybys, no spacecraft has passed by Uranus or Neptune. Many of the things that we do know have been derived by way of telescopic observations and mathematical modeling. Therefore, even minor inaccuracies in our assumptions about material behavior at high pressure can accumulate into vast uncertainties.

However, Morf and Helled's study brings a helpful shift in perspective: Uranus and Neptune are not necessarily a distinct class of ice planets. Instead, they may form a continuum between rocky and gas giants, serving as a middle ground between Earth-type planets and giant gas planets such as Jupiter and Saturn.

Overall Implications for Planet Formation

The implications stretch far beyond our own solar system. Uranus- and Neptune-sized worlds are among the most common types discovered around other stars. Understanding how these two local examples formed may revolutionize the way astronomers think about thousands of distant "mini-Neptunes" and "super-Earths."

If Uranus and Neptune actually vary so substantially in terms of rock versus water composition, it suggests that world construction is not a cookie-cutter process. The composition of each world likely has to do with where it formed within its protoplanetary disk, what materials are present there, and how it interacted with the gas and dust surrounding it.

By merging empirical flexibility with physical consistency, the Zürich scientists' method might also be applied to exoplanets, where researchers might be able to guess what lies under their foggy atmospheres.

Practical Implications of the Research

Getting Uranus and Neptune more accurate is significant for more than the sake of curiosity. They could be a missing piece in the way scientists have understood the diversity of worlds within our own galaxy. Improved modeling of their interiors may make it possible to predict planet formation processes, atmospheric chemistry, and even magnetic field behavior in millions of exoplanets.

Future missions—potentially orbiters or atmospheric probes—could use this model-building paradigm to build better instruments and experiment with alternative theories.

Last but not least, this research contributes to a more nuanced map of exploring not only our outer solar system, but also the vast range of planetary systems beyond.

Research findings are available online in the journal arXiv.

Related Stories

- Researchers solve the mystery of Uranus and Neptune's Magnetic Fields

- James Webb Telescope finds hidden moon orbiting Uranus

- Scientists discover an ocean on Uranus’s moon Miranda

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.

Joshua Shavit

Writer and Editor

Joshua Shavit is a NorCal-based science and technology writer with a passion for exploring the breakthroughs shaping the future. As a co-founder of The Brighter Side of News, he focuses on positive and transformative advancements in technology, physics, engineering, robotics, and astronomy. Joshua's work highlights the innovators behind the ideas, bringing readers closer to the people driving progress.