Roman gladiator vs lion: Surprising discovery in York cemetery

A skeleton found in York shows lion bite marks, giving the first solid proof of Roman gladiator games with animals in Britain.

Skeleton with lion bite marks found in York reveals first proof of Roman human-animal combat far from Rome. (CREDIT: Dea Picture Library)

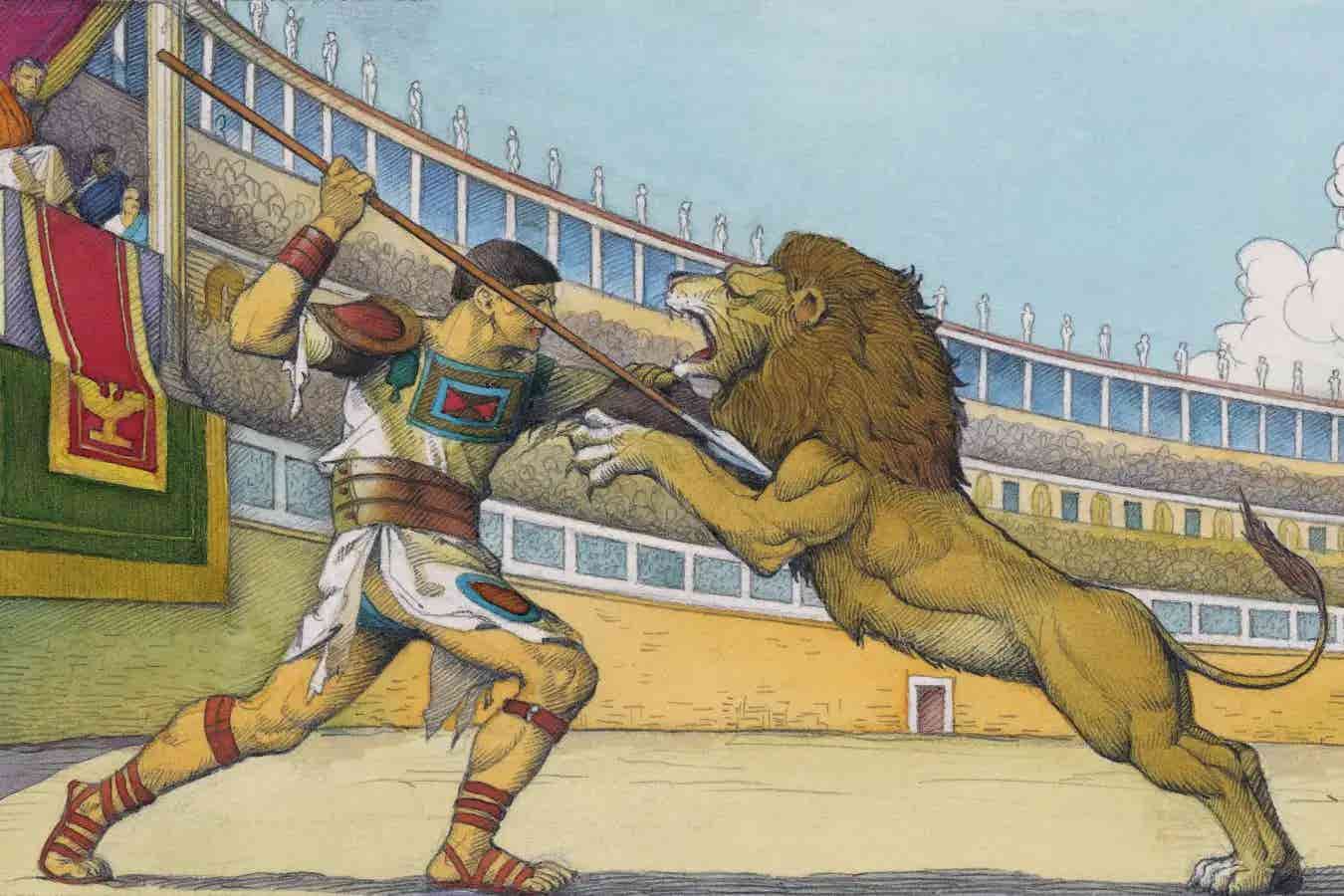

A gruesome but fascinating discovery in an ancient cemetery near York has brought fresh light to the brutal world of Roman gladiators. For the first time in Europe, scientists have found physical evidence showing that humans fought large animals, including lions, in Roman arenas—far from the famed Colosseum. This finding confirms what scholars have long suspected but could never prove through bones alone.

A Skeleton Speaks

The skeleton of a man between 26 and 35 years old was unearthed at Driffield Terrace, one of the best-preserved Roman burial sites believed to hold gladiators. What set this skeleton apart were unusual marks on his bones—bite wounds that matched the size and shape of a lion’s jaw. Researchers from the University of York compared the lesions to bite samples from lions at zoological facilities to confirm the identity of the attacker.

The wounds were not healed, which means the man likely died during or shortly after being mauled. Further analysis showed that someone decapitated him after death, a practice seen in Roman graves. This skeleton lay in a grave alongside two others and was covered with horse bones, suggesting a ritual or symbolic burial.

His remains also revealed other signs of a hard life. Scientists found damage in his spine, probably caused by heavy lifting or repetitive strain, and signs of inflammation in his thigh and lung. He also suffered from malnutrition as a child, though he later recovered. His muscular build and injuries suggest he had been trained for combat. Experts believe he may have served as a Bestiarius—a type of gladiator trained to fight wild animals.

A Gladiator’s Resting Place

Back in 2010, researchers examined 82 strong, young male skeletons at the same site. Most showed healed injuries from violent events and had robust frames built from years of training. Dental enamel tests showed they came from many different parts of the Roman Empire, suggesting they were brought to York for a special purpose—likely to fight for entertainment.

At the time, scientists believed they had found a gladiator graveyard. The presence of grave goods and the way bodies were arranged supported this idea. But without more direct proof, the theory remained open to debate.

Related Stories

That changed with this lion-bitten skeleton. Dr. Malin Holst, who led part of the analysis, said the bite marks prove that the dead at Driffield Terrace were gladiators, not just soldiers or slaves. “This confirms the first osteological evidence of human interaction with large carnivores in a combat or entertainment setting in the Roman world,” she said.

Ancient York’s Arena Culture

This discovery didn’t happen overnight. Archaeologists began digging at Driffield Terrace in 2004. Over time, they found more pieces of a much larger story. The area lies along an old Roman road leading out of York to Tadcaster, a well-traveled route in Roman times. It makes sense that games and events would take place nearby, especially since York—then called Eboracum—was once a major Roman military center.

Tim Thompson, a professor who studied the remains, noted how much of our knowledge about Roman gladiators comes from art and ancient writing. “This discovery provides the first direct, physical evidence that such events took place in this period, reshaping our perception of Roman entertainment culture in the region,” he said.

The idea that lions and other exotic animals were once shipped to cities like York may seem far-fetched, but historical sources confirm it happened. Roman emperors spared no expense to impress crowds with thrilling fights. While people often picture these games in the mighty Colosseum, events also took place across the empire, from small villages to major cities.

Although archaeologists have not yet found an amphitheater in York, the city likely had one. Many high-ranking Roman officials once lived there, including Constantine, who declared himself emperor in York in the year 306. These leaders needed elite entertainment, and gladiator games would have been the highlight of public life.

Death and Glory in the Arena

Gladiators, whether volunteers or slaves, were valuable. Their owners trained them, fed them, and treated them like sports stars. Much like modern athletes, they were expected to perform—and survive—so they could entertain crowds again. If they died, they often received honors in death. Some graves at Driffield Terrace contain gifts meant to help them in the afterlife.

This mix of ritual, violence, and public entertainment is part of what makes Roman culture both shocking and intriguing. The new evidence from York helps fill in gaps and gives a more complete image of how widespread and deadly the gladiator system really was.

David Jennings, CEO of York Archaeology, spoke of the broader meaning behind the discovery. “This gives us a remarkable insight into the life – and death – of this particular individual,” he said. “It is remarkable that the first osteoarchaeological evidence for this kind of gladiatorial combat has been found so far from the Colosseum of Rome, which would have been the classical world’s Wembley Stadium of combat.”

A Closer Look at the Bones

The evidence did not stop at lion bites. The man’s body tells a larger story of strength, suffering, and spectacle. His spine showed signs of strain, likely caused by carrying heavy loads or intense training. Inflammation in his thigh and lung may have caused pain or slowed his movement in battle. Malnutrition as a child would have made early life tough, but he overcame it to grow into a strong adult.

His death—whether in a cage match with a lion or a final event in an arena—marked the end of a brutal life. Experts believe his decapitation followed Roman customs linked to death and possibly honor. The burial with horse bones adds a layer of ritual that suggests his end was part of a larger story or performance.

Holst said this new data helps create a fuller picture of gladiators, who they were, and what they faced. “It also confirms the presence of large cats, and potentially other exotic animals, in arenas in cities such as York,” she explained. “They too had to defend themselves from the threat of death.”

A Wider World of Roman Games

Though the Colosseum in Rome remains the most iconic symbol of Roman bloodsport, the games spread far beyond its walls. Local events entertained crowds in distant corners of the empire, including Britain. Lions, leopards, and other creatures were brought in for combat. Fighters like the man in York risked their lives for glory, survival, or freedom.

As scholars continue to study this unique site, more secrets may come to light. DNA analysis has already started to reveal the wide range of origins for the men buried there. Some came from far-off lands, others possibly from nearby. What united them was their fate—to fight, to die, and to be remembered through their bones.

These bones now tell a vivid story. They confirm what history only hinted at. Far from the glamour of Rome, in the damp soil of northern Britain, a man once faced a lion—and lost.

Research findings are available online in the journal PLOS One.

Note: The article above provided above by The Brighter Side of News.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.