Scientists create lower-gluten wheat that makes tasty bread with fewer celiac triggers

Researchers removed key gluten proteins from wheat without harming baking quality, offering hope to those at risk of celiac disease.

UC Davis scientists reduce wheat’s gluten risk while boosting dough quality in major step for celiac research. (CREDIT: Wheat with reduced allergenicity growing at the UC Davis Agronomy Field Headquarters.)

Gluten makes your bread stretchy and your pasta chewy. But for millions, it causes pain. Around one percent of the global population suffers from celiac disease, a condition triggered by eating gluten. The number is growing, and no cure exists. The only way to manage it is by following a strict gluten-free diet, which is often expensive and difficult to maintain.

Researchers at the University of California, Davis, have made a major step forward. They managed to remove a specific group of gluten proteins in wheat that trigger strong immune reactions. And they did this without hurting the wheat's ability to make good bread.

"The gluten proteins we eliminated are the ones that trigger the strongest response in people with celiac disease," said Jorge Dubcovsky, a wheat geneticist at UC Davis. "Their elimination can reduce the risk of triggering the disease in people without celiac disease."

The Science Behind the Seed

Gluten is made up of two main protein groups: glutenins and gliadins. Together, they create the elastic dough we all know. But these proteins also contain short sequences of amino acids called epitopes. In people with celiac disease, these epitopes can spark an immune reaction that damages the small intestine. Among the most harmful of these are found in a type of gliadin called alpha-gliadin.

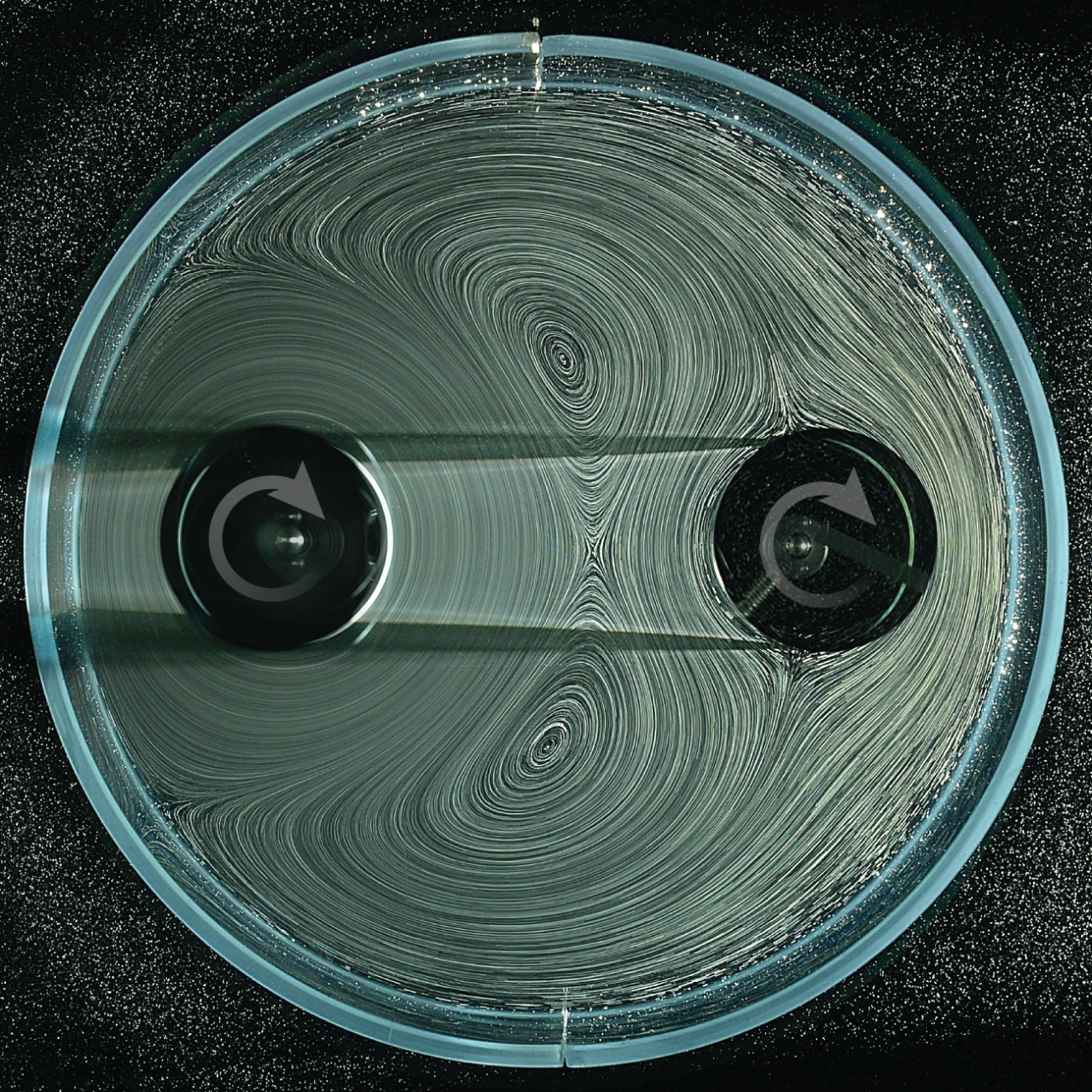

The team used a method called gamma radiation to target and delete the alpha-gliadin genes in wheat. These genes exist in three areas of the wheat genome. The researchers named the deleted versions as Δgli-A2, Δgli-B2, and Δgli-D2. These deletions were carefully analyzed using a method called exome capture.

One deletion, Δgli-D2, stood out. It removed key immunodominant epitopes and boosted the gluten strength of the dough. That means the wheat not only became less likely to trigger celiac disease, it actually became better for baking. "The quality of the flour produced by this wheat is actually, in some cases, improved," said Maria Rottersman, a doctoral student and lead author of the study.

Related Stories

Breadmaking Without Compromise

A major concern was whether the changes would make wheat less suitable for baking. That didn’t happen. The deletion of Δgli-D2 resulted in stronger gluten. This is likely because it removed a special kind of alpha-gliadin with seven cysteines. These proteins often stop the growth of gluten strands, weakening dough. Without them, the gluten network grows longer and stronger.

Wheat samples were tested at the California Wheat Commission and passed baking tests with flying colors. Some even performed better than the unedited wheat. Researchers measured things like gluten strength, elasticity, and how long the dough took to develop. All traits showed equal or improved performance.

"It was previously assumed that the elimination of gliadins would have a negative effect on breadmaking quality," said Dubcovsky. "Our study shows that this is not always the case and that we can reduce wheat allergenicity and improve quality at the same time."

What This Means for Public Health

Celiac disease affects people differently depending on genetics. Those with the HLA-DQ2 allele are at greater risk because their immune system responds to more gluten epitopes. Reducing the total amount of harmful epitopes in wheat may lower the risk for these individuals.

This approach doesn’t aim to make wheat safe for those already diagnosed. Instead, it could help reduce the number of people who develop the disease in the first place. "It becomes a barrier when people are not able to safely eat wheat," said Rottersman. "Alpha-gliadins are definitely candidates for removal in terms of trying to create a less allergenic wheat."

The seeds from these modified lines have been deposited in the Germplasm Resources Information Network, or GRIN. This means they are now publicly available for other researchers and farmers.

A Path Toward Better Wheat

Field trials were conducted at UC Davis to see how the modified wheat performed in real-world conditions. The wheat was grown using typical farming methods and showed no loss in yield. That’s crucial for farmers who might worry about losing profits.

Artisanal bakers and farm-to-table operations are already expressing interest. The new wheat can be planted like any other crop and doesn’t need special handling. It was developed through conventional breeding, not genetic engineering, which may make it more widely accepted.

Backing the research were institutions like the USDA and the Celiac Disease Foundation. The study, published in Theoretical and Applied Genetics, involved many contributors from UC Davis, including experts in proteomics, plant sciences, and baking science.

One exciting finding was that wheat lines with the Δgli-D2 deletion had a higher ratio of glutenins to gliadins. This shift contributes to the improved dough quality. Detailed protein studies showed that removing the harmful alpha-gliadins allowed stronger gluten structures to form.

Even more promising is that this approach may serve as a model for other grains like barley and rye, which also cause problems for people with gluten sensitivities.

This breakthrough won’t make wheat safe for everyone. But it offers a realistic, science-backed step toward a world where more people can eat bread without fear. As more people turn to expensive and restrictive diets, this development gives hope for a better, more inclusive food future.

Note: The article above provided above by The Brighter Side of News.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.