Scientists discover new type of explosion that is brighter than 100 billion stars

Astronomers have unveiled a previously unknown and powerful type of cosmic explosion that dwarfs nearly every supernova ever recorded.

[Sept. 9, 2023: Staff Writer, The Brighter Side of News]

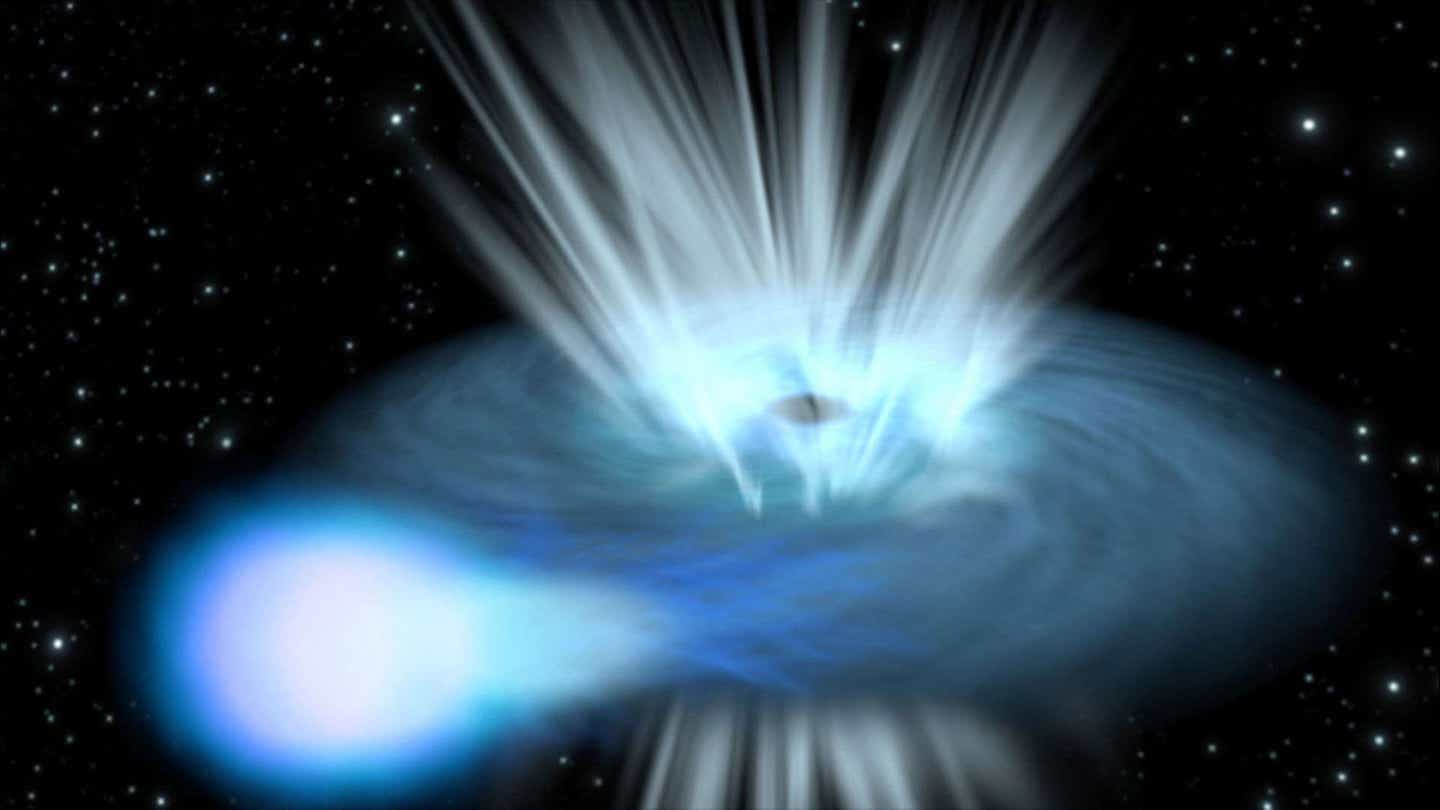

Artists impression of a black hole destroying a nearby star. The researchers believe such a collision may be responsible for this new type of explosion. (CREDIT: ESA / C. Carreau)

In a spectacular astronomical discovery, astronomers have unveiled a previously unknown and powerful type of cosmic explosion, one that dwarfs nearly every supernova ever recorded.

This fleeting yet tremendous explosion shone brighter than 100 billion suns in a mere span of 10 days and, in a stunning display of transience, almost vanished entirely a few weeks thereafter. This rapid surge and fall in luminosity makes the event more ephemeral and radiant than the customary supernova.

The groundbreaking findings, which suggest that this explosive event could signify an entirely novel class of explosions previously untouched in astronomical studies, were published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

"We have named this new class of sources 'Luminous Fast Coolers' or LFCs," elucidated the lead study author Matt Nicholl, an astrophysicist at Queen's University Belfast. "The exquisite data set that we have obtained rules out this being another supernova."

Related Stories

For context, supernovas are luminous detonations resulting from the demise of gargantuan stars, particularly those possessing at least eight times the mass of our Sun. These colossal stars, upon depleting their nuclear fuel, implode and subsequently eject their outer gaseous envelopes into the cosmic void.

Astronomers, with seasoned eyes, observe hundreds of these starry fireworks annually as they flare up before gradually dimming. A typical supernova reaches its zenith of brightness approximately 20 days post ignition, illuminating the universe with an intensity that could outshine several billion suns. Over ensuing months, this stellar glow ebbs away.

However, the LFCs detected aren’t mere supernovas. This is accentuated by the fact that the observed explosion, pinpointed by the Asteroid Terrestrial-Impact Last Alert System (ATLAS) telescope network sprawled across Hawaii, Chile, and South Africa, erupted in a galaxy teeming with sun-like stars. These stars, due to their relatively smaller stature, don’t possess the necessary criteria to evolve into supernovas.

The unusual new blast that has been analysed by the Queen’s researchers is as bright as hundreds of billions of Suns. But it also has another peculiar trait, it lasts less than half as long as typical supernovae. (CREDIT: Queen's University Belfast)

Elaborating on the event's intriguing backdrop, study co-author Shubham Srivastav, a research fellow at Queen's University, stated, "Our data showed that this event happened in a massive, red galaxy two billion light-years away. These galaxies contain billions of stars like our Sun, but they shouldn't have any stars big enough to end up as a supernova."

The novelty of the explosion isn’t just limited to its location. The LFC's luminosity transcended and waned much swifter than conventional supernovas. The subsequent 15 days post-explosion witnessed a dramatic reduction in its brightness by two magnitudes, and shockingly, the explosion's luminosity dwindled to a minuscule 1% of its peak intensity within a month.

Follow-up of AT 2022aedm. Left: multicolor light curves from UV to NIR. Arrows indicate upper limits. The inset shows the early ATLAS flux data with a second-order fit (also shown on the multicolor plot) and time above half-maximum. (CREDIT: Astrophysical Journal Letters)

Given that this explosion failed to align with any recognized supernova profiles, the burning question emerged - has any such occurrence been documented previously? Pursuing an answer, the researchers meticulously sifted through historical telescope surveys, hunting for celestial objects mirroring the recent explosion's luminosity and lifespan. Their perseverance bore fruit, revealing two similar objects, one from a 2009 survey and another from 2020.

Consequently, the research team postulated that these explosive events epitomize a new, albeit exceptionally rare, category of cosmic eruptions. Surprisingly, these don’t seem to be associated with the demise of stars. So, what could LFCs possibly be? Nicholl posited, "The most plausible explanation seems to be a black hole colliding with a star."

Spectroscopic analysis of AT 2022aedm. Left: line identification in the highest signal-to-noise ratio spectra. No unambiguous broad features are identified, but we clearly detect early emission lines of Hα and He ii and, at later times, blueshifted absorption lines of H and He i. (CREDIT: Astrophysical Journal Letters)

However, this theory poses its own set of puzzles. Conventionally, when black holes ensnare and strip materials from adjacent stars in grisly events known as tidal disruption, they emit brilliant X-ray emissions. Yet, none of the identified LFCs displayed any signs of such emissions.

This incongruity suggests potential shortcomings in our current scientific models detailing star-black hole interactions or perhaps, we are just scraping the surface in our understanding of LFCs. The researchers remain undeterred and plan to keep their eyes peeled for more of these enigmatic cosmic eruptions in neighboring galaxies, hopeful that closer observations may unravel the mysteries of the universe.

Note: Materials provided above by The Brighter Side of News. Content may be edited for style and length.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get the Brighter Side of News' newsletter.