Scientists reduce the time for quantum learning tasks from 20 million years to 15 minutes

Entangled light lets researchers learn complex quantum systems millions of times faster than classical methods.

Edited By: Joseph Shavit

Edited By: Joseph Shavit

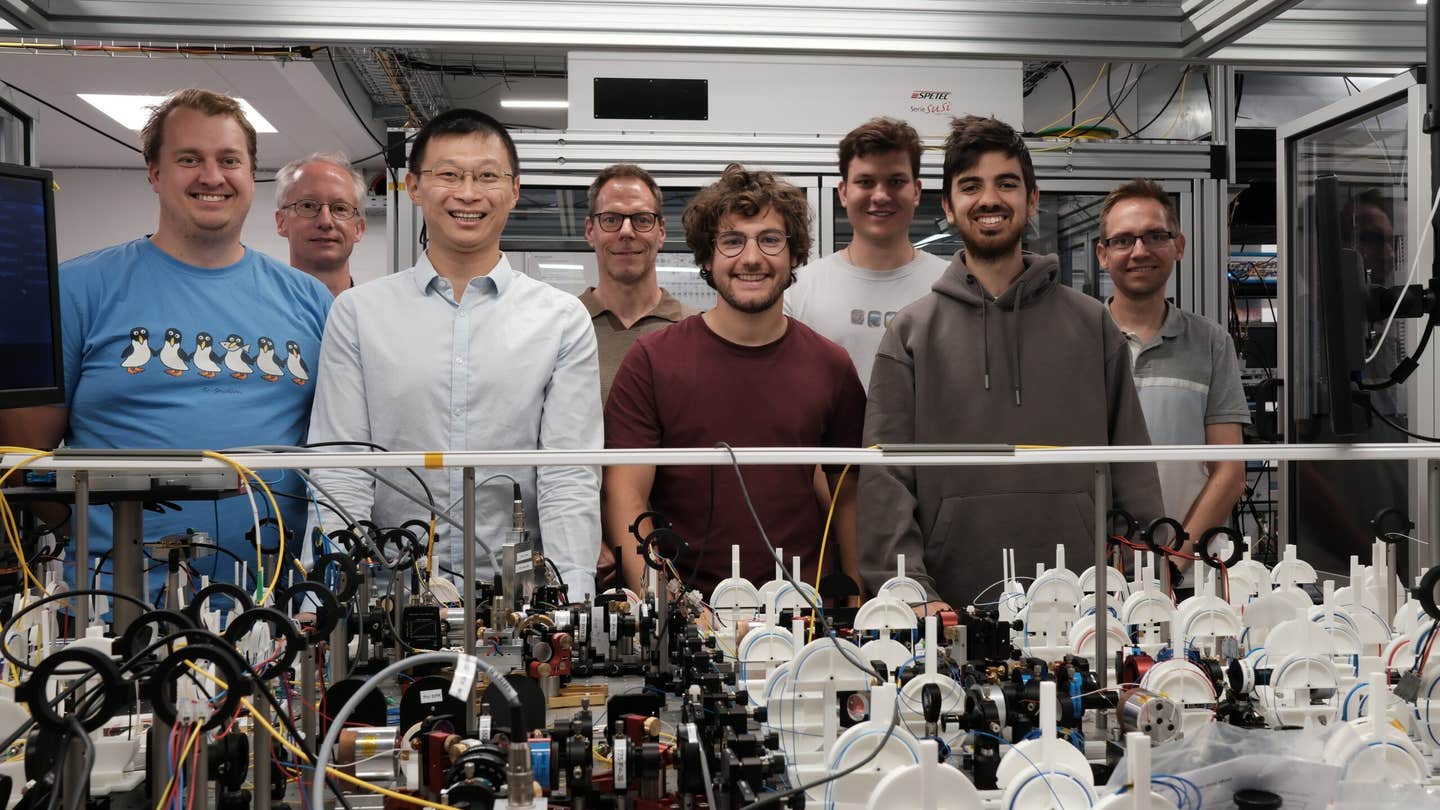

The DTU team (from left): Jens Arnbak Holbøll Nielsen, Axel Bogdan Bregnsbo, Zheng-Hao Liu, Ulrik Lund Andersen, Romain Brunel, Emil Erik Bay Østergaard, Óscar Cordero Boronat, Jonas Schou Neergaard-Nielsen. (CREDIT: Jonas Schou Neergaard-Nielsen)

Learning how a physical system behaves usually means repeating measurements and using statistics to uncover patterns. That approach works well in classical science. Once quantum effects dominate, the rules change. Measurement noise becomes unavoidable, and limits set by Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle restrict what any single measurement can reveal. As systems grow more complex, the number of experiments needed can rise so fast that learning becomes unrealistic.

Researchers at the Technical University of Denmark, working with collaborators in the United States, Canada, and South Korea, now show a way around that barrier. By using entangled light and collective measurements, the team demonstrates a clear quantum learning advantage on a scalable photonic platform. The work appears in the journal Science.

“This is the first proven quantum advantage for a photonic system,” says Ulrik Lund Andersen, a professor at DTU Physics and the study’s corresponding author. “Knowing that such an advantage is possible with a straightforward optical setup should help others look for areas where this approach would pay off, such as sensing and machine learning.”

Why classical learning breaks down in quantum systems

When you try to understand a device or process, you often aim to identify its noise pattern. In optics and sensing, that noise can show up as random changes in amplitude and phase. For quantum systems, these fluctuations are not just technical errors. They are part of the physics.

"Earlier studies showed that classical learning strategies, which measure each probe independently, can require an exponential number of samples as system size increases. Even adaptive methods, where measurements change over time, cannot escape that scaling. Previous experiments using superconducting qubits hinted at quantum advantages, but scaling those systems remains difficult," Andersen told The Brighter Side of News.

"Our new study takes a different path. Instead of qubits, we use a continuous-variable photonic platform. This choice allows us to work with many optical modes at once, exceeding 100 in some tests, and to encode information across time rather than in individual particles," he continued.

Displacement processes at the center of the problem

The learning task focuses on random multi-mode displacement processes. These processes describe noise in bosonic channels, which appear across optical technologies. Any continuous-variable noise channel can be converted into a displacement channel, making the problem widely relevant.

Such processes matter in fields ranging from gravitational-wave detection to Raman spectroscopy and dark-matter searches. They also appear in microscopic force sensing. To learn them, you reconstruct a mathematical object called a characteristic function, which captures the full noise distribution.

The challenge lies in the high-frequency parts of that function. Those regions hold subtle but important features, yet they are the hardest to resolve. Theory predicts that learning them without entanglement demands an exponential number of samples as the number of modes grows.

How entanglement changes the rules

The DTU-led team uses entanglement to overcome that limit. Each probe mode is paired with a memory mode, forming an Einstein–Podolsky–Rosen, or EPR, state. The probe travels through the unknown displacement process. Afterward, the probe and memory are measured together.

These joint measurements reveal correlations in amplitude and phase with a precision set by how strongly the light is squeezed. Because the measurement acts on both modes at once, it avoids the usual uncertainty limits that apply to single probes.

The experiment relies on optical parametric oscillators to generate two-mode squeezed states. The setup runs at telecom wavelengths and uses standard optical components. Importantly, it tolerates ordinary losses. That detail shows the advantage comes from how information is extracted, not from an idealized device.

Learning a complex process with far fewer samples

To test the method, the researchers reconstruct a displacement process with three distinct peaks in its characteristic function. These features are known to be difficult to detect with limited data.

Without squeezing, reconstructions fail quickly in the high-frequency region. Even with 16 modes and hundreds of samples, classical-style strategies cannot recover the true structure. Achieving the needed resolution would require thousands of measurements.

With entanglement, the outcome changes sharply. For 30 modes, unsqueezed strategies fail even with very large sample sizes. When moderate squeezing is applied, accurate reconstructions emerge using the same number of measurements. As squeezing increases, the number of required samples stays nearly constant, even as the number of modes grows.

At the strongest squeezing levels, the improvement reaches 11.8 orders of magnitude. A comparable classical approach would need so many samples that collecting them at the experiment’s one-megahertz rate would take more than 20 million years. The quantum method finishes in about 15 minutes.

Proving the advantage beyond reconstruction

To move beyond visual reconstructions, the team designs a strict hypothesis test. In this game, a dealer prepares one of two possible displacement processes. One contains three peaks. The other follows a Gaussian pattern. You interact with the process a fixed number of times, without knowing which case applies.

Only after all measurements are complete does the dealer reveal where to evaluate an estimator that distinguishes the two families. This structure removes prior hints and sets a clear classical limit.

Experiments and Monte Carlo simulations show that the quantum strategy surpasses that limit. With higher squeezing, the estimator separates the two cases cleanly. As the number of modes increases, the task becomes harder, but stronger squeezing extends the regime where the quantum method succeeds.

In the largest test, involving 120 modes, the success probability remains above anything achievable classically with the same sample size. Matching that performance without entanglement would take centuries of data collection. This corresponds to a provable quantum advantage of about 1.9 orders of magnitude in sample complexity.

What the result means for quantum technology

The findings show that photonic systems, even with realistic noise and loss, can deliver scalable quantum learning advantages. Information spreads across many time modes and is recovered through joint measurements that extract more value from each experiment.

Jonas Schou Neergaard Nielsen, an associate professor at DTU Physics and a co-author, notes that the work is not tied to a single application. “Even though a lot of people are talking about quantum technology and how they outperform classical computers, the fact remains that today, they do not,” he says. “What satisfies us is that we have finally found a quantum mechanical system that does something no classical system will ever be able to do.”

Practical Implications of the Research

This research shows that entanglement can make complex quantum systems learnable within realistic timeframes. In sensing, it could allow faster and more accurate detection of weak signals, such as gravitational waves or tiny forces.

In quantum machine learning, it offers a path toward training models on high-dimensional data that would overwhelm classical methods.

More broadly, it suggests that future quantum devices may gain their edge not from perfect hardware, but from smarter ways of measuring and processing information.

Research findings are available online in the journal Science.

Related Stories

- UCSD physicists develop efficient way to decode quantum systems

- Quantum technologies have reached a critical stage in their growth

- Scientists achieve first-ever quantum teleportation between separate semiconductor chips

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.

Shy Cohen

Writer