Scientists solve the evolutionary mystery of how humans came to walk upright

Harvard-led Nature study links two developmental shifts and key genes to how the human pelvis evolved for bipedal walking.

Edited By: Joseph Shavit

Edited By: Joseph Shavit

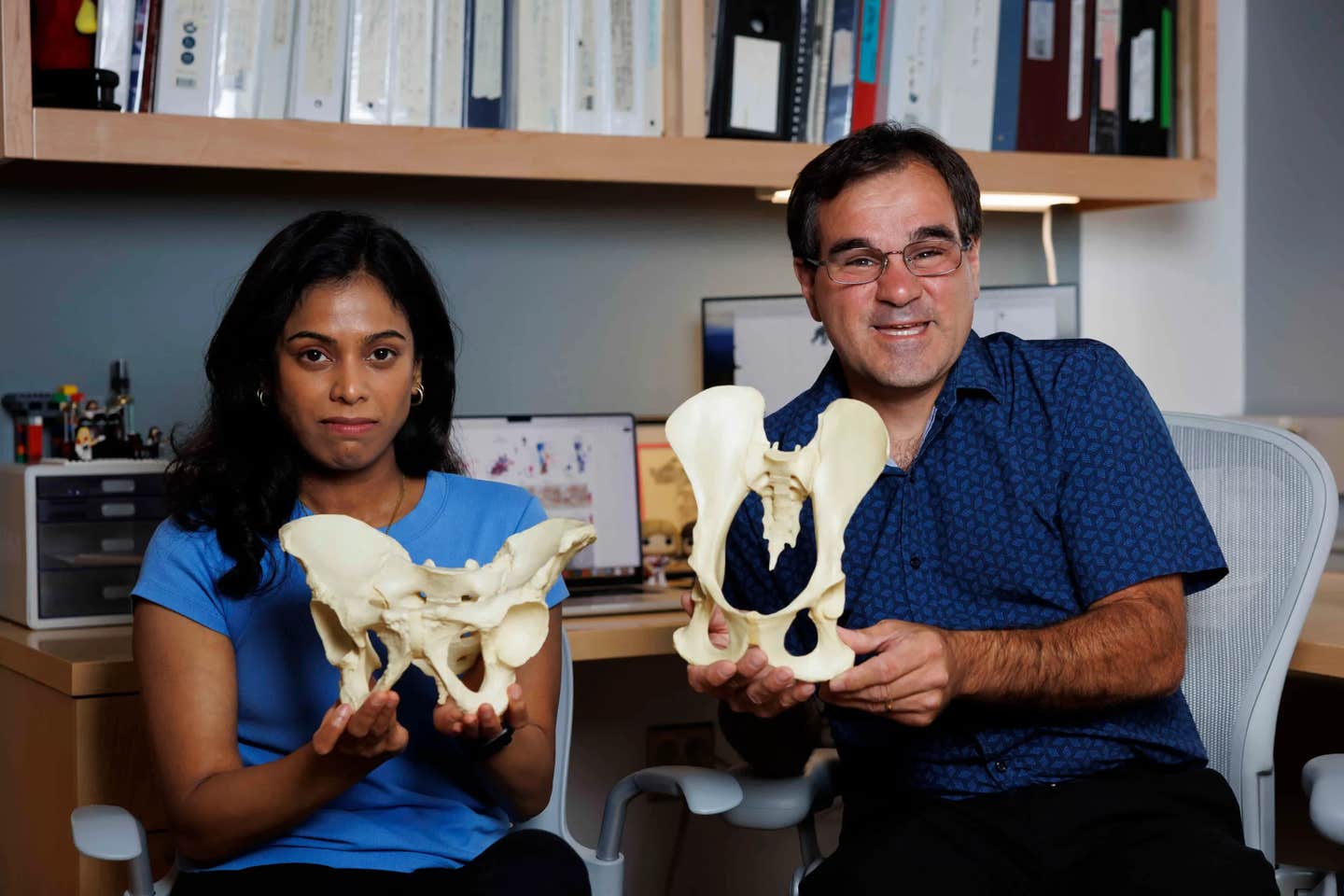

Gayani Senevirathne (left) holds the shorter, wider human pelvis, which evolved from the longer upper hipbones of primates, which Terence Capellini is displaying. (CREDIT: Niles Singer/Harvard Staff Photographer)

The pelvis is often called the keystone of upright movement. It helps explain how human ancestors left life on all fours behind. Yet the “how” has stayed fuzzy for decades. A new Nature study led by Harvard University researchers now points to two major genetic and developmental changes that reshaped the pelvis into a structure built for walking on two legs.

The work was led by Terence Capellini, professor and chair of Harvard’s Department of Human Evolutionary Biology, with Gayani Senevirathne, a postdoctoral fellow in Capellini’s lab, as lead author. The team also drew on human embryonic tissues collected by the Birth Defects Research Laboratory at the University of Washington.

“What we’ve done here is demonstrate that in human evolution there was a complete mechanistic shift,” said Capellini, senior author of the paper. “There’s no parallel to that in other primates. The evolution of novelty , the transition from fins to limbs or the development of bat wings from fingers , often involves massive shifts in how developmental growth occurs. Here we see humans are doing the same thing, but for their pelves.”

What makes the human pelvis different

Anatomists have long known the human pelvis looks unlike any other primate’s. In chimpanzees, bonobos and gorillas, the upper hipbones, called the ilia, are tall and narrow. They sit like thin blades and help anchor climbing muscles.

In humans, those hipbones swing outward into a bowl-like form. The shape supports balance while weight shifts from one leg to the other during walking and running. The new study set out to connect that adult anatomy to the steps that build the pelvis early in development.

“What we have tried to do is integrate different approaches to get a complete story about how the pelvis developed over time,” said Senevirathne, the study’s lead author.

Senevirathne analyzed 128 samples of embryonic tissues from humans and nearly two dozen other primate species. Many came from museum collections in the U.S. and Europe. Some were century-old specimens stored on glass slides or preserved in jars. The group also used CT scans and tissue imaging to track pelvic growth through key early stages.

“The work that Gayani did was a tour de force,” said Capellini. “This was like five projects in one.”

The first shift: a growth plate flips direction

The team’s first big finding involves a growth plate, the cartilage zone that guides how a bone expands. In most lower-body bones, cartilage grows along the bone’s long axis. Later, that cartilage hardens into bone.

Early in development, the human ilium starts out like other primates. Growth lines up head-to-tail. Then, around day 53, the pattern changes sharply. The growth plate reorients by 90 degrees. That single switch helps make the hipbone shorter and wider at the same time.

“Looking at the pelvis, that wasn’t on my radar,” said Capellini. “I was expecting a stepwise progression for shortening it and then widening it. But the histology really revealed that it actually flipped 90 degrees , making it short and wide all at the same time.”

To test whether this was truly unusual, the researchers compared development across primates and mice. In species ranging from mouse lemurs to chimpanzees, the growth plate stayed aligned along the bone’s length. Humans stood out for the perpendicular shift.

The authors suggest this change began around the time human ancestors split from African apes, often estimated at 5 million to 8 million years ago.

The second shift: bone forms from the outside and much later

"The study’s second major change involves how the ilium turns from cartilage into bone. In most animals, bone formation begins in a central zone, then quickly spreads inward as blood vessels grow into the cartilage," Capellini shared with The Brighter Side of News.

"Humans do something different. Bone formation begins near the rear of the pelvis, close to the sacrum, then spreads outward in a radial pattern. At first, mineralization stays mostly on the outside layer rather than pushing deep into the cartilage," he continued.

Even more striking, the team reports that internal bone formation lags far behind the outer shell. They estimate an internal delay of about 16 weeks compared with the outer mineralization. That slow schedule may help the ilium keep its shape while it widens and rotates into a basin-like form.

“Embryonically, at 10 weeks you have a pelvis,” said Capellini as he sketched on a whiteboard. “It looks like this , basin-shaped.”

Genes tied to the new blueprint

To connect anatomy to biology, Senevirathne used single-cell techniques that track which genes switch on in specific cell types. The team identified more than 300 genes involved in building the developing pelvis. Three stood out for their large roles.

Two genes, SOX9 and PTH1R, align with the growth-plate shift. A third gene, RUNX2, aligns with the altered pattern and timing of bone formation. The researchers point to medical evidence that backs up those links.

A mutation in SOX9 causes campomelic dysplasia, a condition associated with abnormally narrow hipbones that lack the normal outward flare. Mutations in PTH1R also link to narrow ilia and other skeletal disorders.

The study also connects pelvic evolution to later pressures, including childbirth. As brains grew larger, a pelvis built for efficient movement also had to allow delivery of babies with bigger heads and broader shoulders. The researchers suggest the delayed ossification pattern may have emerged more recently, perhaps within the last 2 million years, as those pressures intensified.

Capellini argues the findings should change how scientists think about later hominin evolution.

“All fossil hominids from that point on were growing the pelvis differently from any other primate that came before,” said Capellini. “Brain size increases that happen later should not be interpreted in a model of growth like chimpanzee and other primates. The model should be what happens in humans and hominins. The later growth of fetal head size occurred against the backdrop of a new way of new way of making the pelvis.”

Research findings are available online in the journal Nature.

Related Stories

- Harvard study identifies why humans walk upright

- Two ancient cousins of Lucy walked on two legs in different ways

- The surprisingly complex story of how mammals stand and move today

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.

Joshua Shavit

Writer and Editor

Joshua Shavit is a NorCal-based science and technology writer with a passion for exploring the breakthroughs shaping the future. As a co-founder of The Brighter Side of News, he focuses on positive and transformative advancements in technology, physics, engineering, robotics, and astronomy. Joshua's work highlights the innovators behind the ideas, bringing readers closer to the people driving progress.