Scientists use microbes on ISS to extract valuable metals from meteorites

On the ISS, a fungus pulled palladium from meteorite rock while microgravity reshaped what leaches naturally.

Edited By: Joshua Shavit

Edited By: Joshua Shavit

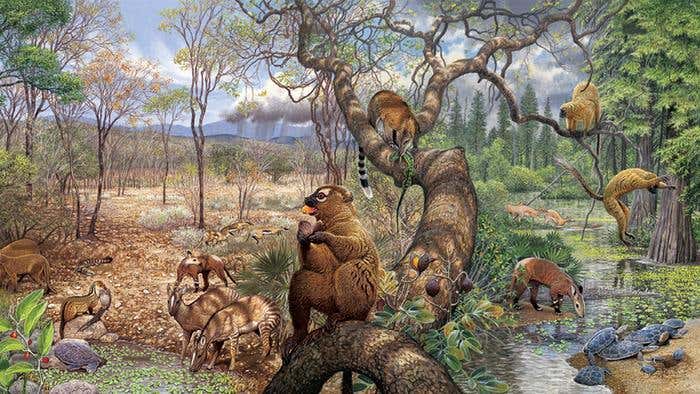

The BioAsteroid experiment. NASA astronaut Michael Scott Hopkins performs the insertion of the experiment containers in KUBIK. (CREDIT: ESA/NASA)

A meteorite chip sat in a small container, bathed in liquid, while the International Space Station floated overhead. Inside, a fungus spread thin threads across the rock. A bacterium built a slick biofilm. The question was simple to ask and harder to test: in microgravity, can microbes pull valuable metals out of asteroid-like material?

A Cornell University and University of Edinburgh team says yes, at least in a proof-of-concept sense, and the fungus did the heavy lifting for one of the most sought-after metals in the sample.

The experiment, called BioAsteroid and reported in npj Microgravity, compared a bacterium (Sphingomonas desiccabilis), a fungus (Penicillium simplicissimum), and a mixed “consortium” of both. Lead author Rosa Santomartino, an assistant professor of biological and environmental engineering at Cornell, worked with co-author Alessandro Stirpe, a research associate in microbiology. Charles Cockell, a professor of astrobiology at the University of Edinburgh, is the senior author.

“This is probably the first experiment of its kind on the International Space Station on meteorite,” Santomartino said.

A space test for “biomining”

Biomining relies on microbes that help break down rock and release useful elements. On Earth, that approach can speed up extraction and reduce the need for toxic chemicals such as cyanides, the paper notes. The space angle is different. If people aim to live and work far from Earth, they will need ways to use local materials, instead of constantly resupplying.

BioAsteroid put that idea into hardware and sent it to orbit. NASA astronaut Michael Scott Hopkins carried out the on-station work, installing the experiment containers into KUBIK incubators. Samples ran for 19 days, while the researchers ran a parallel control experiment on Earth under normal gravity.

The target material was an L-chondrite meteorite, a common type of stony meteorite. Before testing any biology, the team characterized what the rock actually contained. X-ray diffraction showed the dominant minerals were olivine and enstatitic pyroxene, with forsterite ferroan at 47.4±1.6% and ordered enstatite at 29.5±0.4%. Anorthite made up 12.1±1.6%, while melilite and troilite were each a little over 5%.

Bulk elemental analysis found magnesium was the most abundant element at 159.399±18.262 mg/g. Iron came next at 84.502±8.279 mg/g, followed by sulfur at 28.555±2.956 mg/g and manganese at 25.440±2.561 mg/g. Palladium was present too, but at a far smaller concentration, listed as 0.002 μg/g.

What the microbes did to the rock

Microscopy showed that both organisms could colonize the meteorite fragments in orbit and on Earth. The bacterium formed a contiguous biofilm across many areas of the surface in both conditions. The fungus developed mycelia on the rock fragments in both conditions, and the authors did not report major qualitative changes in shape tied to gravity.

Cells often clustered around minerals bearing magnesium, oxygen and silicon, which fits the meteorite’s silicate-rich makeup. They interacted less often with minerals bearing iron and sulfur.

Then came the leaching measurements. The team measured concentrations of 44 elements in the liquid around the rock, using ICP-MS. Statistical analysis flagged 22 elements as potentially relevant for deeper investigation, and the paper focused first on three platinum group elements: ruthenium, palladium and platinum.

Under microgravity, the fungus stood out. Compared with non-biological controls in orbit, P. simplicissimum enhanced mean leaching for all three platinum group elements. In the ISS samples, the paper reports that mean extraction in the presence of the fungus reached 19.29% of the ruthenium in the rock, 11.91% of the palladium, and 0.29% of the platinum.

The “consortium” often looked similar to the fungus alone, but palladium was the exception. In microgravity, the consortium’s palladium extraction dropped to 3.74% of the palladium present in the meteorite, even while ruthenium and platinum tracked closer to the fungal-only condition. The paper describes this as a possible antagonistic effect from the bacterium.

On Earth, the pattern shifted. Enhanced leaching of ruthenium and platinum showed up with both organisms, alone or together, with reported increases spanning 142.2±19.9% to 218.9±67.5% of the non-biological control. Palladium, however, went the other direction under terrestrial gravity. The authors report that palladium leaching was reduced by the presence of the microbial species on Earth.

Microgravity changed the baseline too

One of the more striking results had nothing to do with microbes. The team compared non-biological controls in microgravity versus on Earth, to see how gravity affects “abiotic” leaching.

Palladium behaved dramatically differently. The paper reports mean palladium extraction of 2.2±0.6% of the metal present in microgravity, versus 29.5±6.7% under terrestrial gravity, a 13.6-fold increase on Earth.

Platinum moved in the opposite direction, with 0.2±0.0% in microgravity versus 0.13±0.02% on Earth, a 1.8-fold increase in space. Ruthenium’s mean extraction was higher in microgravity too, 14.8±2.2% in space versus 6.6±2.1% on Earth, though the paper notes the p-value did not indicate a significant difference for ruthenium in that comparison.

Beyond the platinum group, the study reports that abiotic leaching in microgravity changed for 11 elements. Aluminium showed a 6.8-fold increase in microgravity, and iron showed a 4.3-fold increase. Sodium, in contrast, leached more under terrestrial gravity, with a 1.4-fold increase on Earth.

The authors suggest altered fluid dynamics in microgravity, such as reduced convection, could change how quickly dissolved elements move away from a rock surface. They also note that this explanation does not neatly fit every element-specific pattern they observed.

The fungus looked busier in space

To probe what might drive the fungal performance, the team ran a metabolomics analysis on the recovered liquid. This is where they looked for biomolecules, especially secondary metabolites, that could relate to leaching chemistry.

A principal component analysis across all samples showed substantial overlap, with one outlier among the ISS bacterium samples. Yet other analyses suggested space altered metabolism, particularly in fungus-containing samples. When the team looked only at ISS samples, fungus-containing groups formed distinct clusters away from non-biological controls and most of the bacterium samples.

Notably, the paper says that several well-known organic acids associated with leaching, including citric, oxalic, malic and glucuronic acids, were not detected. Instead, the researchers identified other carboxylic acids, siderophore-associated molecules, and compounds they describe as potentially interesting for pharmaceutical and bioplastic production.

The study points to a general trend: fungus-containing samples in microgravity showed more up- or downregulated metabolomic features than comparable Earth samples.

Limits, variability, and what the numbers say

Spaceflight biology comes with constraints, and the authors do not hide them. They report high variability, which they link to differences in microbial growth rates and the meteorite’s heterogeneous composition. The paper also notes that small sample volumes and limited replicates, common in space experiments, may have amplified that variability.

Even with those caveats, the authors argue the fungal signal is hard to ignore. In the Discussion, they report that palladium extraction increased 5.5-fold relative to abiotic controls in microgravity, with leaching yields reaching 549.3±234.4% of the non-biological control.

The bacterium, by contrast, often performed similarly to or worse than non-biological controls for most platinum group elements in microgravity, and the paper suggests its biofilm and extracellular polysaccharides could sometimes protect surfaces from corrosion.

The authors also include an economic back-of-the-envelope, with clear warnings. Using a palladium price of $36.39 per gram cited from kitco.com and retrieved on June 27, 2025, they estimate that palladium extracted under microgravity by the fungus, scaled to a 1000 m³ tank under their experimental conditions, would be about $10. They call that economically negligible. The point, they argue, is not short-term profit, but resource self-sufficiency.

Research findings are available online in the journal npj Microgravity.

The original story "Scientists use microbes on ISS to extract valuable metals from meteorites" is published in The Brighter Side of News.

Related Stories

- Complex building blocks of life form spontaneously in space, study finds

- From bread to Mars: The promise of yeast in space

- Worm experiments expose hidden health risks of deep space travel

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.

Joseph Shavit

Writer, Editor-At-Large and Publisher

Joseph Shavit, based in Los Angeles, is a seasoned science journalist, editor and co-founder of The Brighter Side of News, where he transforms complex discoveries into clear, engaging stories for general readers. With vast experience at major media groups like Times Mirror and Tribune, he writes with both authority and curiosity. His writing focuses on space science, planetary science, quantum mechanics, geology. Known for linking breakthroughs to real-world markets, he highlights how research transitions into products and industries that shape daily life.