Strange iron ‘bar’ discovered inside the Ring Nebula

A UCL and Cardiff-led team using WEAVE on the William Herschel Telescope has found a thin bar of highly ionized iron inside the Ring Nebula

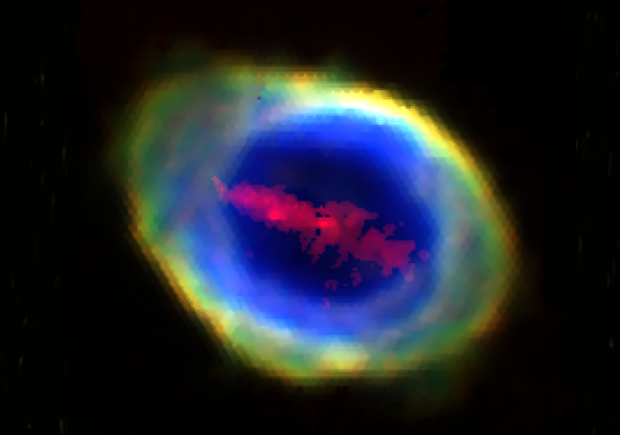

A composite RGB image of the Ring Nebula (also known as Messier 57 and NGC 6720) constructed from four WEAVE/LIFU emission-line images. (CREDIT: Roger Wesson et al / MNRAS)

A famous night-sky object has yielded a surprise: a narrow, bar-shaped cloud made of highly ionized iron. The discovery comes from a European team led by astronomers at University College London and Cardiff University, using a new spectrograph on the William Herschel Telescope.

The object is the Ring Nebula, also called NGC 6720 and M 57. It sits about 2,600 light-years away in the constellation Lyra. It formed roughly 4,000 years ago, after a sunlike star swelled into a red giant and cast off its outer gas. That ejected material now glows as it expands; astronomers call this short-lived phase a planetary nebula.

Lead author Dr Roger Wesson, based jointly at UCL’s Department of Physics & Astronomy and Cardiff University, said the new data revealed something no one had reported before. “Even though the Ring Nebula has been studied using many different telescopes and instruments, WEAVE has allowed us to observe it in a new way, providing so much more detail than before. By obtaining a spectrum continuously across the whole nebula, we can create images of the nebula at any wavelength and determine its chemical composition at any position.

“When we processed the data and scrolled through the images, one thing popped out as clear as anything; this previously unknown ‘bar’ of ionized iron atoms, in the middle of the familiar and iconic ring.”

How the team found the iron bar

The work, described in Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, used WEAVE, a recently installed instrument on the Isaac Newton Group’s 4.2-meter William Herschel Telescope. The key mode was WEAVE’s Large Integral Field Unit, or LIFU. It uses hundreds of optical fibers to collect spectra across a wide patch of sky, instead of sampling one thin line at a time.

That matters because older long-slit methods can miss narrow features unless the slit lands in the right spot. With LIFU, the team built an optical “data cube” that contains a spectrum at each position across the bright ring. They also compared the new optical maps with infrared images from the James Webb Space Telescope, which show the nebula’s structure in a different light.

The bar fits inside the nebula’s inner region and runs along the major axis. In plain terms, it looks like a thin strip laid across the center of the ring. The team estimates it stretches about 50 arcseconds on the sky. In physical size, they describe it as roughly 500 times Pluto’s orbital distance. They also estimate the iron atoms in the feature add up to a mass comparable to Mars.

What “highly ionized” really means

The bar stands out most strongly in an emission line near 4,227 angstroms, identified as [Fe v]. The team also detected several [Fe vi] lines in the same region. Those detections matter because they indicate the bar is not a random artifact; multiple iron ion species appear in the same narrow structure.

These ions require intense energy. To make them, the gas must be exposed to photons in roughly the 55 to 100 electron-volt range. Yet the iron maps do not simply trace the nebula’s hottest or most strongly ionized zones. Other lines, including helium and argon features that often highlight energetic regions, show different shapes and, in some cases, gaps where the iron bar sits.

To measure conditions inside the bar, the researchers extracted a spectrum from a region centered near the nebula’s central star. They estimated electron density at about 460 particles per cubic centimeter. They used an oxygen-based temperature around 11,300 kelvins for abundance work, because those lines were well detected and less vulnerable to certain system effects.

From the bar’s iron lines, the team derived a combined abundance of about 1.3 × 10⁻7 relative to hydrogen for the measured ion stages. Compared with a solar iron-to-hydrogen value of 3.2 × 10⁻5, that indicates iron is still depleted in the gas, by about a factor of 250. The study treats that as an upper limit, because unmeasured ion stages and line-of-sight mixing can complicate the calculation.

Clues from motion and dust, plus a lingering mystery

At first glance, the bar looks jet-like, which might suggest a fast outflow from the central star. But velocity measurements do not line up with a simple jet picture. The iron lines show redshifts relative to other emission lines, yet the iron velocities look similar on both sides of the star within uncertainties. That pattern does not match what you would expect from a bipolar flow pointed partly toward and away from Earth.

The team also compared the optical iron map with Webb images. Several infrared filters show linear features consistent with molecular hydrogen on either side of a lane that aligns with the iron emission. In other filters that trace dust continuum more strongly, a dark lane sits where the optical iron brightens. The authors interpret that anticorrelation as a sign that dust may be breaking apart along the bar, releasing iron back into the gas.

Even with those hints, the origin remains unclear. Co-author Professor Janet Drew, also based at UCL Physics & Astronomy shared with The Brighter Side of News: “We definitely need to know more; particularly whether any other chemical elements co-exist with the newly-detected iron, as this would probably tell us the right class of model to pursue. Right now, we are missing this important information.”

One possibility is that the bar records an unrecognized step in how the dying star expelled its gas. Another is more dramatic: the iron could be an arc of plasma created when a rocky planet was vaporized during the star’s earlier expansion. The team plans follow-up observations with higher spectral resolution to test these ideas.

Dr Wesson said, “It would be very surprising if the iron bar in the Ring is unique. So hopefully, as we observe and analyze more nebulae created in the same way, we will discover more examples of this phenomenon, which will help us to understand where the iron comes from.”

Professor Scott Trager, WEAVE Project Scientist based at the University of Groningen, added: “The discovery of this fascinating, previously unknown structure in a night-sky jewel, beloved by sky watchers across the Northern Hemisphere, demonstrates the amazing capabilities of WEAVE. We look forward to many more discoveries from this new instrument.”

Practical Implications of the Research

This finding strengthens a basic point about modern astronomy: new tools can still change what you think you know about well-studied objects. Full-field spectroscopy can reveal narrow features that older methods could miss, which may reshape how researchers interpret the late stages of sunlike stars.

The work also affects how scientists track chemical recycling in the galaxy. Planetary nebulae help return forged elements, including carbon and nitrogen, to interstellar space, and that material later becomes part of new stars and planets. If dust destruction is releasing iron into gas in specific lanes, models of how elements move between dust and gas may need refinement.

Finally, the discovery sets up targeted next steps. Higher-resolution spectra could separate overlapping gas components and clarify whether the bar traces an outflow, a distinct internal structure, or even the aftermath of a destroyed planet. That knowledge would sharpen forecasts for the Sun’s far future and improve chemical maps of many nebulae beyond this iconic one.

Research findings are available online in the journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

Related Stories

- Butterfly Nebula’s Hidden Heart Reveals the Building Blocks of Planets

- Astronomers find hidden channels of hot gas connecting our solar system to distant stars

- Stunning new images of the Ring Nebula captured by Webb telescope

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.

Joseph Shavit

Writer, Editor-At-Large and Publisher

Joseph Shavit, based in Los Angeles, is a seasoned science journalist, editor and co-founder of The Brighter Side of News, where he transforms complex discoveries into clear, engaging stories for general readers. With vast experience at major media groups like Times Mirror and Tribune, he writes with both authority and curiosity. His writing focuses on space science, planetary science, quantum mechanics, geology. Known for linking breakthroughs to real-world markets, he highlights how research transitions into products and industries that shape daily life.