The brain’s building blocks: Why your mind adapts better than AI

New Princeton research shows your brain reuses mental building blocks to learn faster and adapt, offering clues for better AI and brain care.

Edited By: Joseph Shavit

Edited By: Joseph Shavit

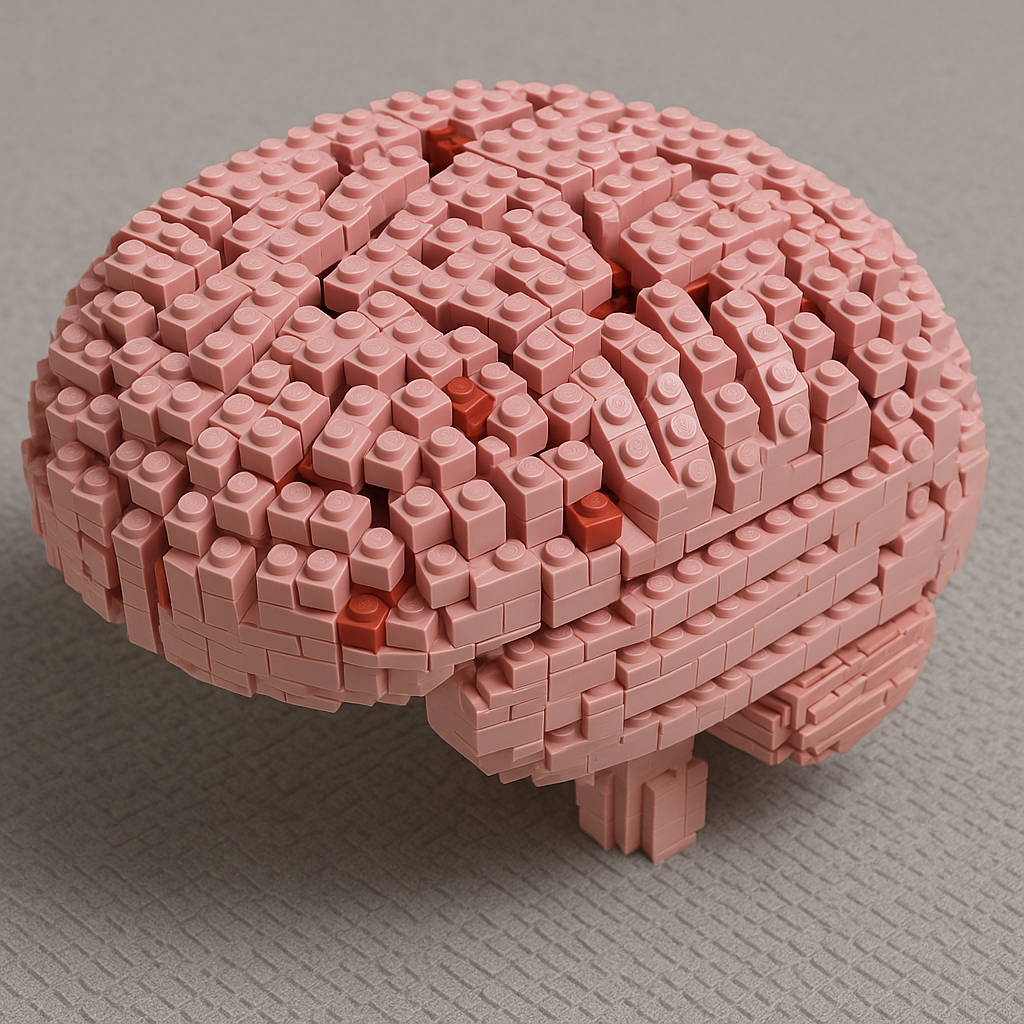

A new study shows that the brain solves hard problems by reusing simple mental parts across many tasks, much like snapping together pieces of a toy set. (CREDIT: AI-generated / The Brighter Side of News)

A pair of monkeys staring at colored shapes in a Princeton lab may have brought you closer to understanding how your own mind works. A new study shows that the brain solves hard problems by reusing simple mental parts across many tasks, much like snapping together pieces of a toy set. The work helps explain why you can move from cooking dinner to learning new software without starting from zero each time.

Scientists have long puzzled over how the brain links small actions into more complex behavior. You learn when fruit is ripe, then apply that skill while shopping, cooking and choosing meals. Your brain does not rebuild each skill every time. It reuses what it already knows and mixes those skills in fresh ways.

In the study, Princeton University researchers trained two male rhesus macaques to handle three related visual games. Each trial showed a squidgy image that changed in color and form. The animal had to judge either the shape or the color, then signal the answer with a fast eye move to one of four targets. A quick glance across the screen became its voice.

Two tasks focused on color, one on shape. The trick was in how the answers were reported. One color game shared its eye directions with the shape game. The other color game used a different set of eye directions. The monkeys were never told which game was running. They had to deduce the rule from feedback, then adjust when the rule changed without warning.

Both monkeys did well. They beat 80 percent accuracy on two games and topped 90 percent on the third. When the rule flipped, they did not fall apart. They tested guesses, learned fast and settled into the new pattern. The hardest switch came when the same eye directions were used but the rule changed from shape to color. In that case, early errors were common, yet accuracy climbed within about 75 trials.

Inside the Brain While It Learns

To see what your brain might be doing in similar moments, the team recorded activity from more than 1,000 neurons across five brain areas at once. These included regions that guide sight, movement and decision making.

Patterns emerged quickly. Signals that marked the current task appeared across areas. Color and shape signals followed the image. Plans for the eye move appeared next, then news about reward.

Many neurons did double duty. One cell might respond to color and the task itself. This mix of roles packed more meaning into each cell and helped the brain stay flexible.

The biggest surprise showed up in the prefrontal cortex, a region near the forehead tied to planning and control. There, the same neural patterns were used to represent color across both color games, even though the eye moves differed. When the team trained a computer to read color from brain activity in one game, it could still read color in the other.

The same reuse happened for eye moves. Codes learned from the shape game worked in the linked color game. It was as if the brain kept a shared library of parts and pulled the right ones for the job.

“Cognitive Legos” at Work

The findings landed in the journal Nature on Nov. 26 and drew notice for what they imply about intelligence.

“State-of-the-art AI models can reach human, or even super-human, performance on individual tasks. But they struggle to learn and perform many different tasks,” said Tim Buschman, Ph.D., the study’s senior author and associate director of the Princeton Neuroscience Institute. “We found that the brain is flexible because it can reuse components of cognition in many different tasks. By snapping together these ‘cognitive Legos,’ the brain is able to build new tasks.”

Lead author Sina Tafazoli, Ph.D., offered a plain example. “If you already know how to bake bread, you can use this ability to bake a cake without relearning how to bake from scratch,” he said. “You repurpose existing skills, using an oven, measuring ingredients, kneading dough, and combine them with new ones, like whipping batter and making frosting, to create something entirely different.”

In the monkeys, that meant pairing a block that judged color with a block that moved the eyes in a certain way. When the game changed, the brain swapped one block for another and carried on.

The team also saw the brain fade out parts it did not need. When color mattered, color signals grew stronger and shape faded. When the rule flipped, the volume knob turned the other way. “The brain has a limited capacity for cognitive control,” Tafazoli said. “You have to compress some of your abilities so that you can focus on those that are currently important.”

Why Brains Beat Machines at Flexibility

If you have ever watched a program forget one skill when it learns another, you have seen a problem called catastrophic interference. Tafazoli put it this way: “When a machine or a neural network learns something new, they forget and overwrite previous memories. If an artificial neural network knows how to bake a cake but then learns to bake cookies, it will forget how to bake a cake.”

Your brain handles this better by keeping parts separate, then recombining them as needed. That design may point the way to smarter machines.

The research also hints at medical payoffs. Some people with brain injury or mental illness struggle to shift rules or apply skills in new settings. If the trouble traces to broken connections among these mental parts, treatments could aim to restore that network.

“Imagine being able to help people regain the ability to shift strategies, learn new routines, or adapt to change,” Tafazoli said. “In the long run, understanding how the brain reuses and recombines knowledge could help us design therapies that restore that process.”

For now, a simple lab task has revealed a deep truth. Intelligence grows from reuse. Your brain builds the new from the old, one snapped piece at a time.

Practical Implications of the Research

The work points toward AI systems that learn faster by reusing core skills instead of rebuilding them for every task. That could make software better at learning on the fly without forgetting earlier lessons.

In medicine, the findings could guide therapies for people who struggle with rule switching after brain injury or in conditions like schizophrenia and obsessive compulsive disorder. By targeting how mental parts are reused, doctors may help patients regain flexibility in daily life.

The study also offers tools to track learning by reading brain signals tied to task belief, which could improve training methods in schools and clinics.

Research findings are available online in the journal Nature.

Related Stories

- Life may be reshaping our bodies and brains faster than evolution can handle

- MIT professor reveals the origin of consciousness and thought in the brain

- AI-powered 'mind captioning' tool turns brain activity into clear text

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.

Shy Cohen

Writer