White rocks on Mars point to ancient rainfall and a wetter planet

Light-colored stones in Jezero crater reveal Mars may have experienced rainfall and long wet periods billions of years ago.

Edited By: Joshua Shavit

Edited By: Joshua Shavit

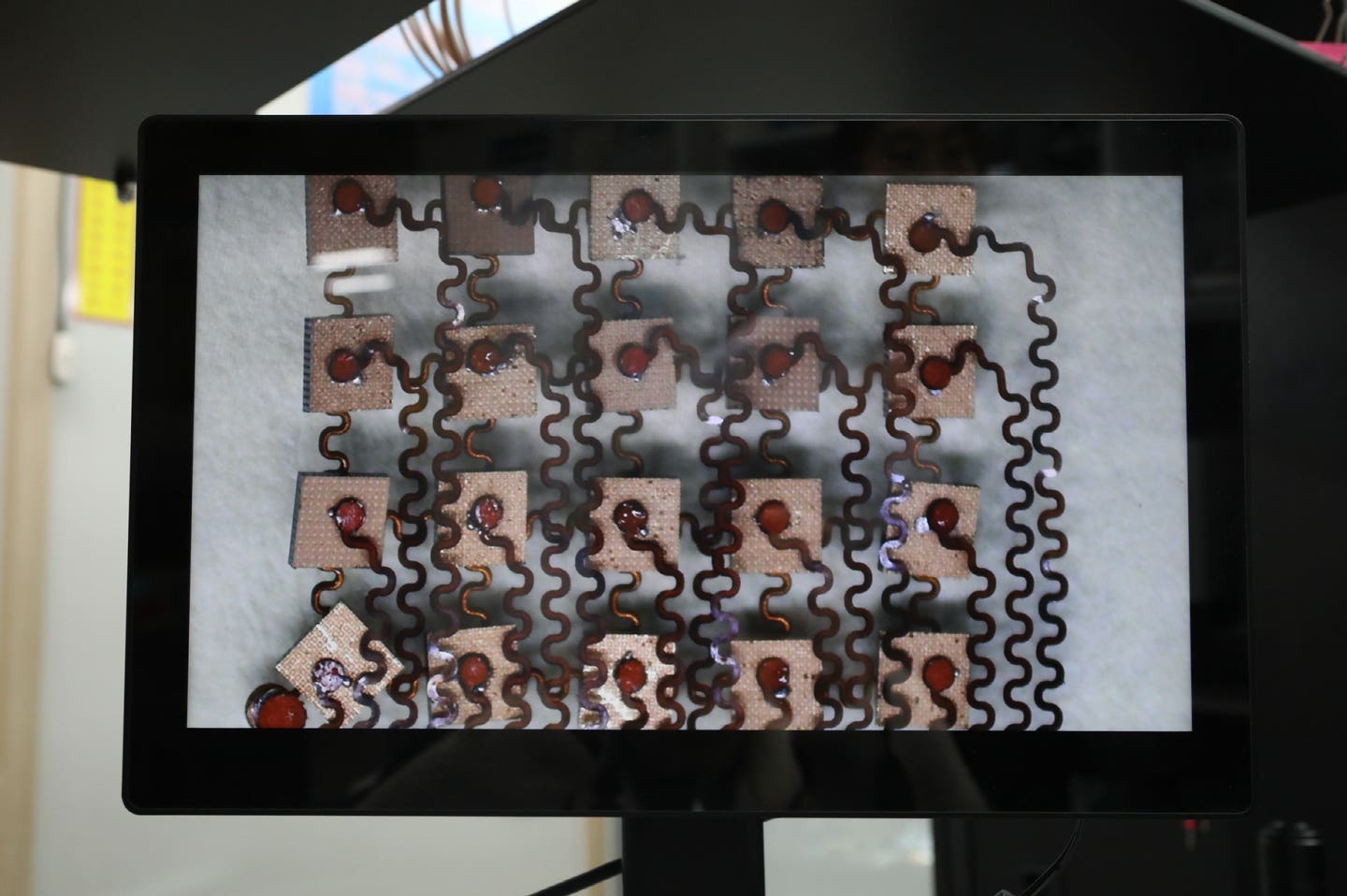

Pale rocks found by Perseverance suggest Mars once had heavy rain and long-lasting water that may support past life. (CREDIT: NASA/JPL-Caltech/MSSS)

Light-colored rocks scattered across Mars have become a quiet clue to a louder story about the planet’s past. NASA’s Perseverance rover keeps finding pale pebbles, cobbles and even small boulders lying loose on the floor of Jezero crater and across its ancient river delta. They look out of place against the darker bedrock. They are not attached to anything, which is why scientists call them “float rocks.” Their chemistry suggests they traveled from elsewhere and landed here long ago.

As the rover zapped and scanned these fragments, researchers noticed something odd. Many are packed with aluminum and carry the distinct signal of kaolin-group minerals such as kaolinite and halloysite. On Earth, those minerals typically form where liquid water weathers rock for long periods. That discovery raised a simple but powerful question: are these pieces of ancient Martian soils?

So far, about 20 of the pale rocks have been probed with SuperCam and Mastcam-Z. Some contain between 17 and 45 percent aluminum oxide and very little iron. Others are rich in silica, with more than 90 percent silicon dioxide. A few even hold nickel at levels that match ore bodies on Earth. Combined, the results point to rocks that were profoundly altered by water before they broke apart and later reached Jezero.

A trail of pale stones

Perseverance first found these rocks on the crater floor. Then they appeared again on the front of the fan where a river once poured into a lake. They also dot the top of that fan. Sizes vary from pebbles you could pocket to boulders that would challenge two people to lift. Their colors range from bone white to dusty gray and tan.

One cluster stood out when the rover reached it around mission day 912. There, dozens of fragments lay strewn across an area the size of a small room. Multispectral images revealed that many glowed differently in near-infrared light, hinting at stark differences from the surrounding terrain and from each other.

Within this mix, a “hydrated” group grabbed attention. Targets called Chignik, Rainbow Curve, Elk Mountain and Coral Bay show signs of water locked inside their minerals. Their spectra include a mark near 2.21 micrometers from aluminum linked to hydroxyl groups, and another near 1.9 micrometers from molecular water. In simpler terms, these rocks still hold evidence of moisture at the atomic level.

Other fragments look different. Some appear dehydrated and contain aluminum oxides and spinel-group minerals. A few boast nickel above one percent by weight. One standout, named AEGIS 910A, is nearly pure silica and bears the fingerprint of hydrated silica. The diversity suggests more than one story fed these stones into the crater.

What the rover can read from a distance

Because many of the rocks are small, the rover could not safely press its contact tools against them. Instead, scientists relied on remote instruments. SuperCam’s laser measured elements such as aluminum, silicon and nickel, while its spectrometer searched for mineral clues. Mastcam-Z supplied context and fine color detail.

To interpret what they saw, researchers compared the Martian data with Earth examples. They studied deeply weathered soils near San Diego that formed about 55 million years ago. They analyzed a much older weathering profile in southern Africa known as the Hekpoort paleosol, dated to about 2.2 billion years. They also looked at kaolin formed by hot fluids in places such as Iran, Malaysia and Argentina.

The match that mattered most appeared between Mars and Earth’s worn landscapes, not its hot springs. The spectra of the San Diego paleosol line up closely with the target Chignik, including the telltale kaolin pattern. Chemical measures of weathering also overlap. Chignik shows strong loss of easily dissolved elements, much like the Earth soils. Another close parallel comes from the iron-poor “pallid zone” of the Hekpoort profile, which plots in nearly the same range as some of the Jezero rocks.

Titanium adds weight to that view. In long-term soil formation, titanium often becomes more concentrated because it does not move easily. Chignik and several other Martian samples contain titanium in amounts similar to the Earth soils and higher than most hydrothermal deposits. That pattern fits slow, wet weathering better than sudden heating by hot fluids.

Nickel complicates the picture. High nickel often forms in deeply weathered layers on ultramafic rocks on Earth. Yet the Martian fragments lack the iron and magnesium expected in classic laterites. If nickel entered their story, it likely did so under unusual conditions.

Searching for their original home

The float rocks did not grow where Perseverance found them. Satellite data provide a few promising leads. Instruments aboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter have mapped aluminum-rich clays across the wider Jezero region. On the crater’s southwest rim, light-toned outcrops and broken blocks show the same clay signals. One small patch sits just one to two kilometers from the rover’s route.

Farther west, a long light-colored outcrop marks part of an ancient channel. Upstream, a lonely butte also shows traces of aluminum clays. Together, these sites hint at a layered crust in which aluminum clays once lay over iron and magnesium clays. Erosion, impacts or flowing water could have freed pieces and carried them into the crater.

One scenario ties the evidence together. Volcanic rocks near the surface slowly altered into clay-rich layers under wet conditions. Over time, burial or heat hardened parts of those layers into stone. Later, flooding, ice or impacts broke them loose and sent fragments downslope into Jezero.

Signs of a wetter Mars

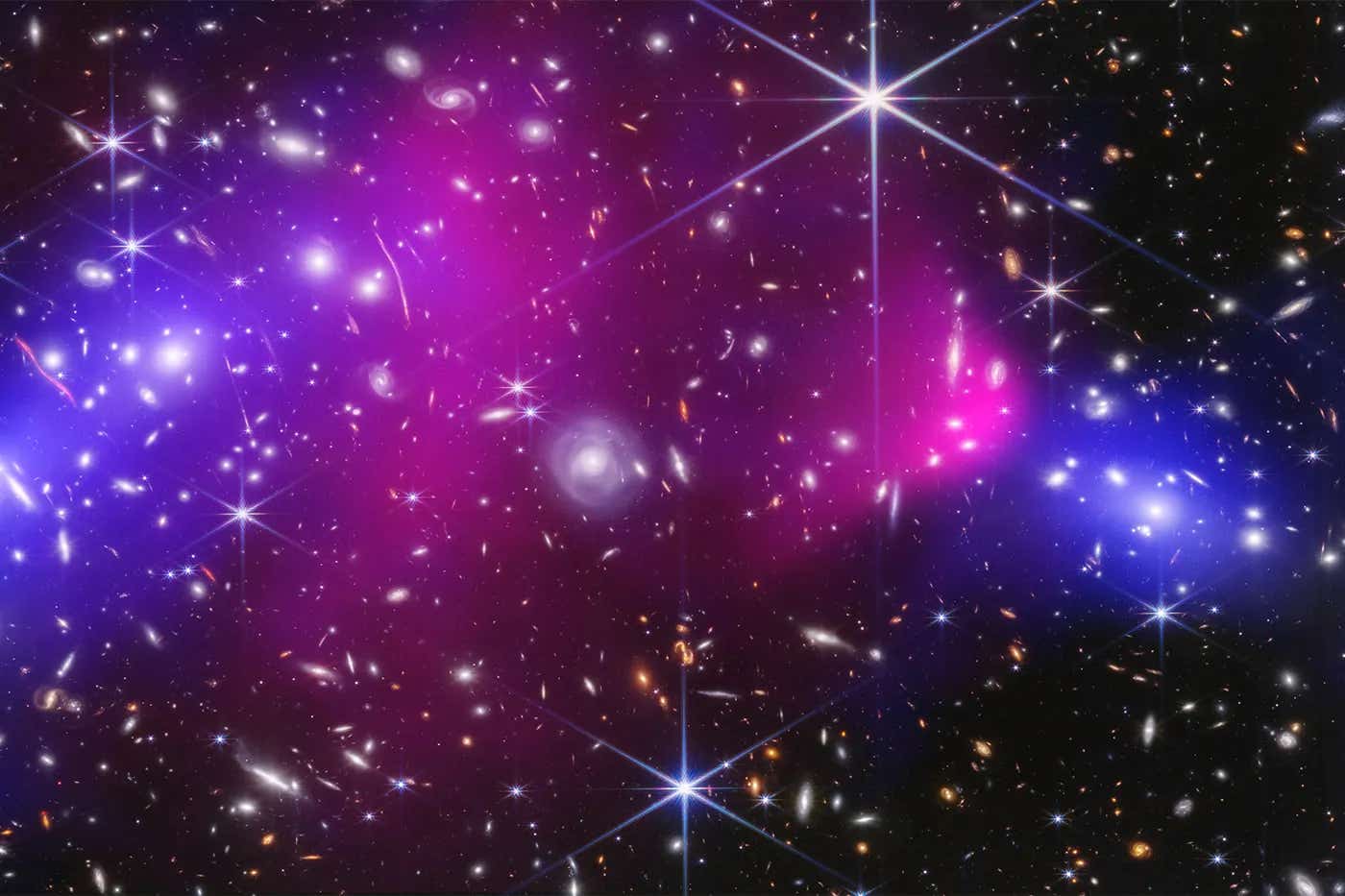

Whether born as soils or shaped by hydrothermal systems, these rocks demand abundant water. To strip away many elements while leaving aluminum and titanium behind, water had to course through the rock in huge volumes. Such conditions fit a period early in Mars’ history, when the planet was warmer and wetter than it is now.

If the rocks truly formed as soils, they imply rainfall lasting thousands to millions of years. Lead author Adrian Broz of Purdue University connects that idea to Earth’s tropics, where kaolinite often develops. “All life uses water,” Broz said. “So when we think about the possibility of these rocks on Mars representing a rainfall-driven environment, that is a really incredible, habitable place where life could have thrived if it were ever on Mars.”

Purdue planetary scientist Briony Horgan, a longtime planner for the rover, agrees that the stakes are high. “Elsewhere on Mars, rocks like these are probably some of the most important outcrops we’ve seen from orbit because they are just so hard to form,” she said. “You need so much water that we think these could be evidence of an ancient warmer and wetter climate where there was rain falling for millions of years.”

The study, published Monday in Communications Earth & Environment, also points to another twist. Minerals like kaolinite hold water inside their crystal structure. On a planet without plate tectonics, that water can become locked away for good. Over billions of years, that process may have helped dry Mars from within.

Perseverance plans to visit larger clay-bearing outcrops soon. Those sites could settle whether the pale stones are true soils, the products of heated fluids or a blend of both. Either answer reshapes the story of Mars. The scattered white rocks now whisper of rivers, rain and a world that once felt far less remote.

Research findings are available online in the journal Communications Earth & Environment.

Related Stories

- Time moves faster on Mars than on Earth, study finds

- Scientists discover 16 giant river networks on ancient Mars where life could have thrived

- Martian dust storms crackle with 'mini lightning,' revealing a hidden electric Mars

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.

Joseph Shavit

Writer, Editor-At-Large and Publisher

Joseph Shavit, based in Los Angeles, is a seasoned science journalist, editor and co-founder of The Brighter Side of News, where he transforms complex discoveries into clear, engaging stories for general readers. With vast experience at major media groups like Times Mirror and Tribune, he writes with both authority and curiosity. His writing focuses on space science, planetary science, quantum mechanics, geology. Known for linking breakthroughs to real-world markets, he highlights how research transitions into products and industries that shape daily life.