Scientists discover America’s largest impact crater from 35 million years ago

About 35 million years ago, an asteroid struck the ocean off the East Coast of North America, leaving behind a massive impact crater.

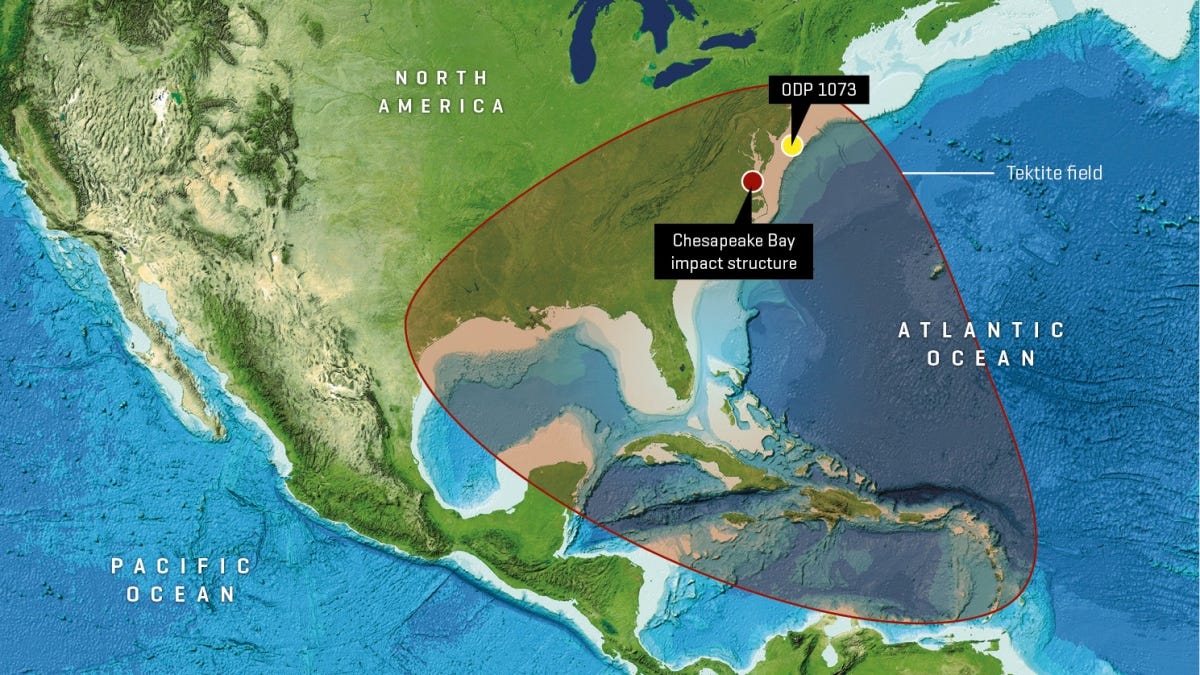

An asteroid struck the East Coast of North America 35 million years ago. Ejected material from the impact site was distributed over an area of at least four million square miles. (CREDIT: GEBCO world map 2014, www.gebco.net)

Roughly 35 million years ago, a massive asteroid slammed into the Atlantic Ocean near what’s now the East Coast. The impact struck with such force that it carved out a vast crater, later buried beneath the present-day Chesapeake Bay.

The explosion unleashed chaos across the region. It sparked enormous fires, sent shockwaves that triggered earthquakes, and hurled molten glass into the sky. A towering air blast raced outward, and a massive tsunami tore across what are now Virginia and Maryland, reshaping the landscape.

Remnant Debris and Sediment

That ancient impact crater stretches about 25 miles across. Over time, layers of sediment completely hid it from view. Scientists only confirmed its existence in the early 1990s, thanks to drilling operations that uncovered solid geological evidence.

It still holds the title of the largest known impact crater in the United States. On a global scale, it ranks as the 15th biggest ever discovered—a reminder of the asteroid’s sheer power.

The explosion didn’t just carve a hole in the crust. It launched a colossal amount of material into the sky. Among the debris were tektites, bits of natural glass created by meteorite impacts, and zircon crystals blasted by the shock.

That airborne debris rained back down across an enormous region. It formed what scientists now call the North American tektite strewn field—an ejecta blanket covering around 4 million square miles. That’s ten times bigger than Texas. While some of it fell on land, much of it hit the sea, rapidly cooled, and settled on the ocean floor.

Scale and Timing of Impact

To better understand the scale and timing of the event, researchers analyzed samples from the Ocean Drilling Project’s site 1073. Marc Biren from Arizona State University's School of Earth and Space Exploration led the effort to study these deep-sea cores.

Alongside Jo-Anne Wartho, Matthijs Van Soest, and Kip Hodges, the team used uranium-thorium-helium dating to examine the samples. This advanced method helped pin down when the impact occurred and how long it took for the materials to cool and settle, offering a clearer picture of one of North America’s most violent geological moments.

Related Stories

Their findings were recently published in Meteoritics & Planetary Science.

“Determining accurate and precise ages of impact events is vital in our understanding of Earth's history,” Biren said. “In recent years, for example, the scientific community has realized the importance of impact events on Earth’s geological and biological history, including the 65-million-year-old dinosaur mass extinction event linked to the large Chicxulub impact crater.”

The Role of Zircon Crystals

The team focused on zircon crystals, which preserve evidence of shock metamorphism caused by the high pressures and temperatures of impact events. These crystals, about the thickness of a human hair, were central to their investigation.

“Key to our investigation were zircon — or more precisely: zirconium silicate — crystals found in oceanic sediments of a borehole almost 400 kilometers (250 miles) northeast of the impact site in the Atlantic Ocean,” said co-author Wartho, who started the study as a lab manager at the Mass Spectrometry Lab at ASU.

For this study, Biren collaborated with Wartho (now at GEOMAR Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research Kiel), Van Soest, and Hodges to prepare samples for analysis and date zircon crystals using the uranium-thorium-helium method. Biren identified and processed shocked zircon fragments for imaging and chemical analysis with an electron microprobe.

“This research adds a tool for investigators dating terrestrial impact structures,” Biren said. “Our results demonstrate the uranium-thorium-helium dating method’s viability for use in similar cases, where shocked materials were ejected away from the crater and then allowed to cool quickly, especially in cases where the sample size is small.”

Effects on Planetary Development

The study not only contributes to the understanding of the Chesapeake Bay impact event but also highlights the broader significance of impact events on Earth’s geological and biological history.

The ability to accurately date such events enhances our comprehension of their effects on the planet’s development and the history of life.

Five Largest Craters on Earth

The five largest impact craters on Earth by diameter are:

Vredefort Crater (South Africa) – ~250–300 km

- Age: ~2.02 billion years

- The largest and oldest confirmed impact structure on Earth, located in South Africa. The original crater has been eroded over time, but the remaining structure provides valuable insights into ancient impact events.

Chicxulub Crater (Mexico) – ~180 km

- Age: ~66 million years

- This crater, located beneath the Yucatán Peninsula, is linked to the mass extinction event that wiped out the dinosaurs. It is one of the best-preserved large impact craters on Earth.

Sudbury Basin (Canada) – ~130 km

- Age: ~1.85 billion years

- Located in Ontario, Canada, the Sudbury Basin is one of the oldest impact structures on Earth. It has been heavily modified by erosion and subsequent geological processes.

Popigai Crater (Russia) – ~90 km

- Age: ~35.7 million years

- Situated in Siberia, the Popigai Crater is one of the largest impact structures in Russia. The impact event is believed to have contributed to a minor extinction event.

Manicouagan Crater (Canada) – ~85 km

- Age: ~214 million years

- Located in Quebec, Canada, this well-preserved crater is known for its distinct ring-shaped lake. It is one of the best-studied impact structures on Earth.

These impact craters provide critical evidence of past asteroid or comet collisions and their effects on Earth's geological and biological history.

Note: Materials provided above by The Brighter Side of News. Content may be edited for style and length.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.