Groundbreaking research study finds the upper age limit for humans

For more than a century, doctors, statisticians, and philosophers have wrestled with a timeless question: How long can people really live?

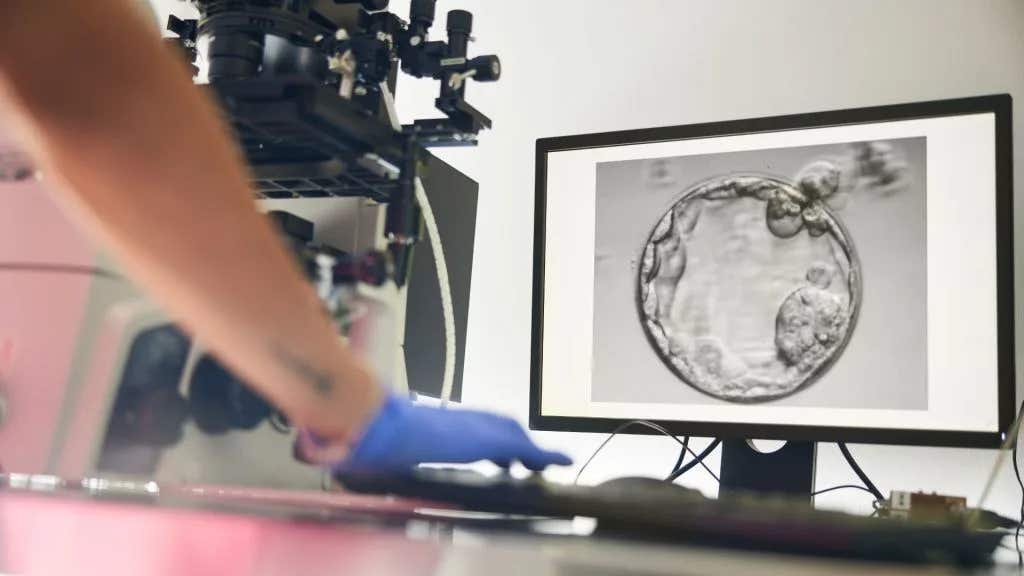

Dutch and international studies suggest humans may face a natural lifespan ceiling. (CREDIT: Shutterstock)

For more than a century, doctors, statisticians, and philosophers have wrestled with a timeless question: How long can people really live? With vaccines, antibiotics, safer childbirth, and better nutrition, life expectancy has steadily risen around the world. Yet the record ages of the very oldest among us have stayed stubbornly the same.

A team of Dutch researchers now believes they may have found an answer. Drawing on three decades of data covering more than 75,000 deaths, scientists at Tilburg University and Erasmus University concluded that women top out around 115.7 years and men at about 114.1. The finding suggests a ceiling—at least under current conditions.

“On average, people live longer, but the very oldest among us have not gotten older over the last thirty years,” explained Professor John Einmahl, one of the study’s lead authors. “There is certainly some kind of a wall here.”

Life Expectancy vs. Lifespan

To understand why this matters, it helps to separate two often-confused terms: life expectancy and lifespan. Life expectancy reflects the average age people are likely to reach within a population. It has been rising sharply thanks to fewer deaths at younger ages and better medical care throughout adulthood.

Lifespan, by contrast, refers to the maximum number of years an individual can live. If many people reach their 90s and even 100, average life expectancy grows, but if the record ages remain unchanged, then lifespan may be capped.

In the Netherlands, the number of people celebrating their 95th birthday has nearly tripled in recent decades. Still, the highest ages at death have not moved upward. This paradox—longer average lives but stable maximum age—has fueled debate among scientists. Are we brushing against a natural biological boundary?

Related Stories

- Breakthrough study reverses age-related memory decline - paving way for human trials

- Scientists discover what drives the maximum lifespan potential of mammals

Evidence Across the Globe

The Dutch findings echo research in the United States, where scientists recently proposed a similar limit. Yet some American teams went further, claiming the very oldest individuals were actually living shorter lives than before. Einmahl and his colleagues disagreed. By applying a specialized statistical tool called Extreme Value Theory—often used to study rare, extreme events like major floods or earthquakes—they showed that maximum lifespan has barely budged in decades.

Their results fit neatly with global demographic data. A larger international study reviewed records from 41 countries using three major databases: the Human Mortality Database, the International Database on Longevity, and records maintained by the Gerontological Research Group. These datasets confirmed the same picture. While survival rates at older ages improved through much of the 20th century, the gains slowed after about 1980 and leveled off beyond the age of 100.

Earlier in history, maximum age at death rose steadily. In Sweden, for example, records showed consistent increases through the 1800s and early 1900s. In Japan, France, and the United States, the maximum reported age at death also climbed through the 1970s and 1980s. Then the pattern stalled. Since the mid-1990s, maximum reported age at death has hovered around 115, regardless of country. Jeanne Calment of France, who lived 122 years and 164 days before her death in 1997, remains unmatched.

To check that this was not a fluke, scientists looked at the top five highest ages at death each year rather than only the record-holder. They also tracked the average age at death among people who lived beyond 110. All the results converged: there has been no upward trend in more than a generation. Models suggest that the odds of someone reaching 125 in any given year are less than one in ten thousand.

Why a Ceiling Might Exist

So why do lives stop stretching further? Researchers caution against the idea that humans are genetically programmed to die at a certain age. Instead, they argue that natural selection shaped our biology to focus on development, growth, and reproduction early in life—not indefinite maintenance of the body in extreme old age.

Over the decades, repair systems in cells and tissues fight off wear and damage. But these systems themselves are limited. At very advanced ages, the slow accumulation of tiny flaws overwhelms those protections. Incremental improvements in healthcare can keep more people alive into their 80s, 90s, and even 100s, but they may not be enough to break past the biological constraints at 115.

Still, the existence of an apparent ceiling does not mean humanity is stuck forever. The researchers emphasize that radical breakthroughs—like targeted genetic therapies, stem cell repair, or new cellular engineering techniques—could, in theory, extend the upper boundary. But those are very different from the broad public health measures that have raised average life expectancy so far.

For now, the message is clear. More people will likely enjoy long, healthy lives into very old age, but the odds of anyone outliving Jeanne Calment remain slim. The focus, many experts say, should be on expanding “healthspan”—the number of years lived without major disability—rather than expecting record lifespans to keep climbing.

The Debate Continues

Not every scientist agrees with the Dutch team’s conclusion. Some researchers argue that statistical methods leave room for the possibility of longer lifespans in the future. They suggest that with enough time—or by interpreting the data differently—the maximum could still rise. Einmahl and his colleagues are careful on this point. They do not claim an unbreakable barrier, only that the data show strong evidence for a practical limit near 115 years under current conditions.

Their work has already drawn attention across the scientific world and is on track for publication in a peer-reviewed journal. Whether or not other teams confirm the same plateau, the findings frame the debate more sharply: average life expectancy and maximum lifespan may not follow the same trajectory.

Practical Implications of the Research

These findings carry weight far beyond the lab. If most people can expect to live into their 80s or 90s but the record age remains steady, then governments, families, and healthcare systems must prepare for more elderly citizens but not necessarily more supercentenarians. The real challenge will be making those extra years as healthy as possible.

For researchers, the results point to two tracks. On one hand, continued investment in public health can raise life expectancy and reduce suffering in old age. On the other hand, pushing the biological ceiling itself may require a different frontier of science—genetic, cellular, and molecular tools that could one day rewrite the boundaries of aging.

For now, though, the evidence suggests humanity has reached a natural limit.

Some of the longest living humans on record

Jeanne Calment (122 years, 164 days)

- Born: February 21, 1875, in Arles, France

- Died: August 4, 1997

- Significance: Calment holds the record as the oldest verified human. She credited her longevity to a diet rich in olive oil and chocolate, as well as an active lifestyle.

Kane Tanaka (119 years, 107 days)

- Born: January 2, 1903, in Fukuoka, Japan

- Died: April 19, 2022

- Significance: Tanaka was recognized as the world’s oldest living person by Guinness World Records in 2019. She enjoyed board games, solving puzzles, and soft drinks.

Sarah Knauss (119 years, 97 days)

- Born: September 24, 1880, in Pennsylvania, USA

- Died: December 30, 1999

- Significance: Knauss lived through three centuries and was known for her calm demeanor.

Lucile Randon (Sister André) (118 years, 340 days)

- Born: February 11, 1904, in Alès, France

- Died: January 17, 2023

- Significance: A nun for most of her life, Randon attributed her long life to daily prayer and chocolate.

Maria Branyas Morera (116+ years, still living as of November 2024)

- Born: March 4, 1907, in San Francisco, USA

- Current residence: Catalonia, Spain

- Significance: Currently holds the title of the world’s oldest living person.

Jiroemon Kimura (116 years, 54 days)

- Born: April 19, 1897, in Kyoto, Japan

- Died: June 12, 2013

- Significance: The oldest verified male, Kimura credited his longevity to eating small portions of food.

These individuals' ages have been verified through extensive documentation, distinguishing them from other claims of extreme longevity that lack sufficient proof.

Note: Materials provided above by The Brighter Side of News. Content may be edited for style and length.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.