500 year-old ‘Bible map’ reveals how maps reinvented faith and nations

A Cambridge study reveals how Bible maps helped shape modern borders, changing how people read Scripture and imagine nations.

Edited By: Joshua Shavit

Edited By: Joshua Shavit

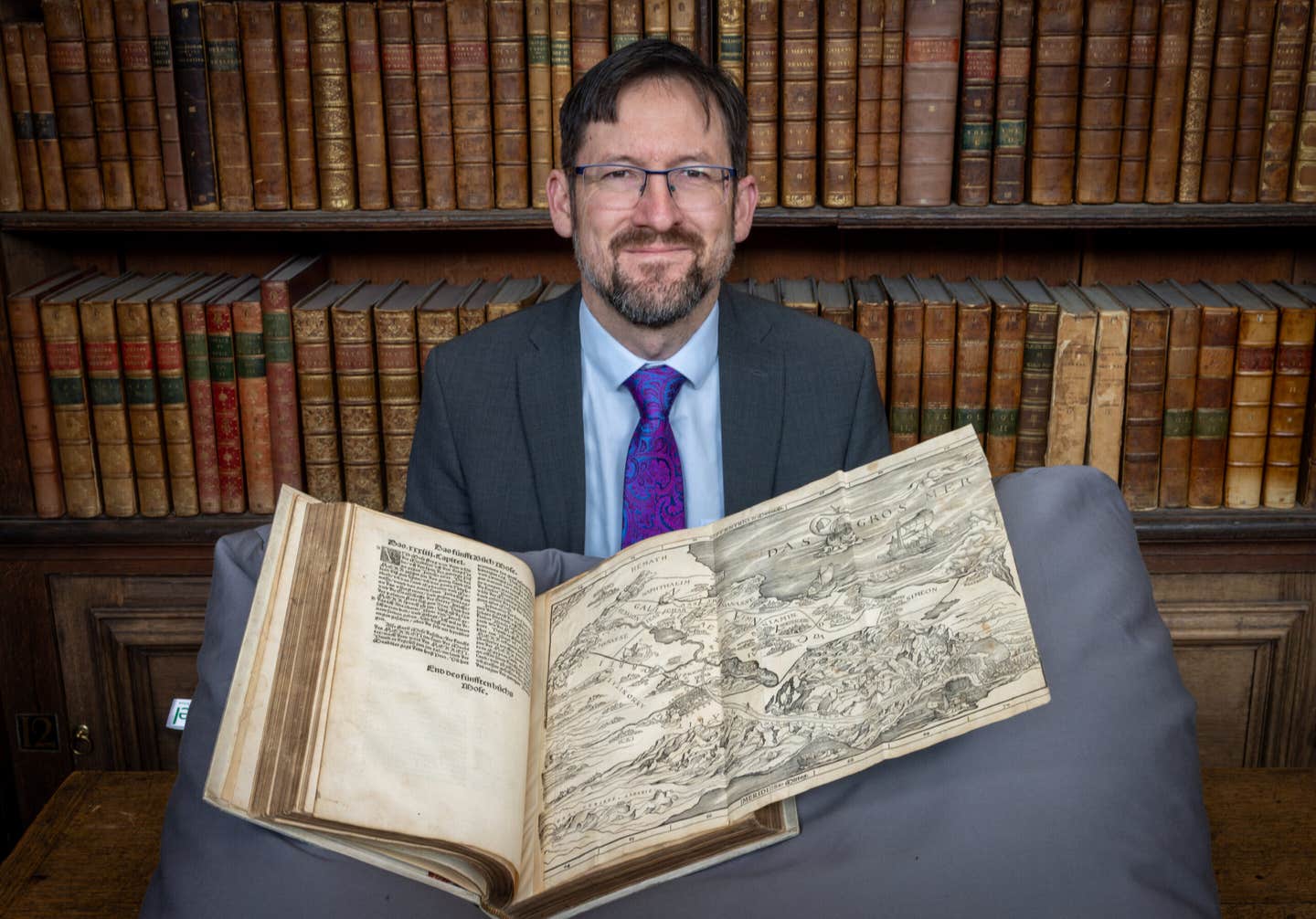

Professor Nathan MacDonald with Christopher Froschauer’s 1525 Old Testament open at Lucas Cranach the Elder’s map of the Holy Land, in the Wren Library, Trinity College, Cambridge. (CREDIT: University of Cambridge)

Coloring the world into tidy blocks with sharp edges feels natural today. Nations look solid on a classroom map. But that way of seeing the planet had to be learned, and a surprising teacher helped shape it: the Bible.

A new study from the University of Cambridge traces part of our border mindset to maps of the Holy Land tucked into early printed Bibles and atlases. Those drawings did more than guide readers. They quietly trained Europe to think in straight lines about land, faith, and power.

Nathan MacDonald, Professor of the Interpretation of the Old Testament at the University of Cambridge, says one moment stands out. In 1525, a Zürich printer released the first Bible to include a map of the Holy Land. Lucas Cranach the Elder drew it. The book did not travel far, and copies are now rare. Trinity College Cambridge keeps one in its Wren Library.

The map arrived with a blunder that might have doomed it. It was printed backward. The Mediterranean Sea appeared east of Palestine.

“This is simultaneously one of publishing’s greatest failures and triumphs,” MacDonald says. “They printed the map backwards so the Mediterranean appears to the east of Palestine. People in Europe knew so little about this part of the world that no one in the workshop seems to have realised. But this map transformed the Bible forever and today most Bibles contain maps.”

The mistake did not stop the influence. Cranach’s map showed Israel carved into twelve tribal territories and traced the wilderness route to the Promised Land. It borrowed from older medieval models, which already drew tribal lines with care. Yet when this picture entered a printed Bible, it reached readers in a new way. It put the story of Scripture onto a grid.

Virtual Pilgrimage on Paper

In the Reformation world, images in churches were often banned. Maps were allowed. They became a new focus for devotion.

“When they cast their eyes over Cranach’s map, pausing at Mount Carmel, Nazareth, the River Jordan and Jericho, people were taken on a virtual pilgrimage,” MacDonald says. “In their mind's eye, they travelled across the map, encountering the sacred story as they did so.”

The timing mattered. Swiss churches stressed literal reading of Scripture. A map made distant places feel firm and real. Joshua’s list of lands and towns, which can read like a tangle of names, suddenly looked ordered. Boundaries felt fixed.

“Joshua 13–19 doesn’t offer an entirely coherent, consistent picture of what land and cities were occupied by the different tribes. There are several discrepancies,” MacDonald says. “The map helped readers to make sense of things even if it wasn’t geographically accurate.”

The Bible was not alone in changing. Atlases of the time also evolved. A few decades earlier, maps rarely showed borders. By the mid-1600s, most did. The Holy Land led the shift. Its clean lines arrived early and stayed.

This did not begin in Zürich. Medieval Christians had been drawing tribal lines for centuries. Those lines carried a faith claim, not a political one. The land once promised to Israel, many believed, now belonged to the church in a spiritual sense. A huge late medieval map tied to pilgrim guides showed tribal names in red ink across Palestine. It did not argue for a state. It argued for inheritance.

Then printing spread the image beyond monasteries and courts to kitchens and workshops. The meaning of the lines changed with the audience.

When Lines Became Power

Over time, borders on paper started to look like borders on earth. What shifted on atlases flowed back into how readers understood Scripture.

MacDonald argues that verses far from the Holy Land slowly picked up a new sheen. Genesis 10, the “Table of Nations,” lists peoples descended from Noah’s sons. It says little about fences or frontiers. Yet by the 1600s, legal writers and preachers began to speak as if the world had once been surveyed and neatly divided.

A famous example is the jurist John Selden. In his 1635 book arguing that seas could be owned like land, he read Genesis as proof of early national ownership. The sons of Noah, he said, had set “bounds.” From that move, coastlines and waters also looked ownable.

Other writers followed. They imagined lots drawn, plots assigned, and islands claimed in ancient times. One commentator even wondered whether Britain itself had been marked out at the beginning. A chapter with few borders in the text became a model for a world of many borders in the mind.

MacDonald sums up the cycle in plain terms. “Early modern notions of the nation were influenced by the Bible, but the interpretation of the sacred text was itself shaped by new political theories that emerged in the early modern period. The Bible was both the agent of change, and its object.”

The Past in Today’s Border Talk

The echo still sounds. MacDonald points to a recent U.S. Customs and Border Protection recruitment video. A helicopter flies over the U.S.-Mexico line. A voice quotes Isaiah 6:8: “Then I heard the voice of the Lord saying, ‘Whom shall I send? And who will go for us?’”

For MacDonald, that moment shows the risk of simple answers.

“For many people, the Bible remains an important guide to their basic beliefs about nation states and borders,” he says. “They regard these ideas as biblically authorized and therefore true and right in a fundamental way.”

He worries that certainty built on slender readings can harden arguments. Even modern tools stumble. “When I asked ChatGPT and Google Gemini whether borders are biblical, they both simply answered ‘yes’,” he says. “The reality is more complex.”

The study, published in The Journal of Theological Studies, does not claim the Bible invented the nation state. It shows something subtler. Maps of the Holy Land taught readers to picture land as divided spaces. Atlases made that style normal. Then readers carried it back to Scriptures that were never meant as border manuals.

In other words, the lines taught the book, and the book taught the lines.

Practical Implications of the Research

This research gives you tools to question claims that borders come straight from Scripture. It can cool debates where faith is used to seal policy as beyond doubt. It also helps teachers explain how texts and technologies shape one another.

For mapmakers, clergy, and citizens, the work encourages care. It asks you to notice when a picture feels ancient but is, in fact, new. That awareness can open space for better conversations about land, belief, and belonging.

Research findings are available online in The Journal of Theological Studies.

Related Stories

- Pope Francis and the Vatican just created an "AI Bible" reshaping faith in the Digital Age

- Biblical chapter of Matthew rediscovered after 1,500 years in hiding

- Medieval scholar declared the Shroud of Turin a fake centuries ago

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.

Joseph Shavit

Writer, Editor-At-Large and Publisher

Joseph Shavit, based in Los Angeles, is a seasoned science journalist, editor and co-founder of The Brighter Side of News, where he transforms complex discoveries into clear, engaging stories for general readers. With vast experience at major media groups like Times Mirror and Tribune, he writes with both authority and curiosity. His writing focuses on space science, planetary science, quantum mechanics, geology. Known for linking breakthroughs to real-world markets, he highlights how research transitions into products and industries that shape daily life.