AI helps scientists read dinosaur footprints, offering new clues to ancient life

Dinosaur footprints outnumber bones, but they are hard to interpret. A new AI study reveals how machine learning can help identify who made them.

Edited By: Joseph Shavit

Edited By: Joseph Shavit

Dinosaur footprints outnumber bones, but they are hard to interpret. A new AI study reveals how machine learning can help identify who made them. (CREDIT: Shutterstock)

Dinosaur skeletons often dominate museum halls, from the towering Tyrannosaurus rex known as Sue in Chicago to Sophie the Stegosaurus in London. These fossils shape how you picture dinosaurs. Yet bones are rare compared with another kind of evidence dinosaurs left behind. Their footprints appear far more often in the fossil record and may tell deeper stories about how these animals lived, moved, and evolved.

Recently published results from a project by Helmholtz-Zentrum Berlin physicists Gregor Hartmann and paleontologist Steve Brusatte from the University of Edinburgh demonstrate how artificial intelligence can assist in developing answers to questions about the behaviors and lifestyles of dinosaurs based on their fossilized imprints. The paper uses algorithms to sort through and classify dinosaur foot imprints without the aid of human labels. This approach provides new insights into which organisms created specific tracks and how those tracks reflect potential evolutionary histories of dinosaurs.

Dinosaur foot impressions are created when an animal walks over soft, moist soil that later solidifies into hard rock and retains its shape for millions of years as it undergoes geological changes. For example, during the Mesozoic Era (approximately 252 million to 66 million years ago), dinosaurs were active on all continents, as evidenced by fossilized footprints found in geologic strata from that period. These tracks have been discovered in various parts of the world, such as the western coast of the United Kingdom, mountains in Italy, and the Cal Orcko formation in Bolivia.

Fossils Versus Footprints

Skeletons provide an incredible amount of detail regarding a dinosaur’s structure and how that dinosaur looked. In contrast, a single dinosaur’s footprint or footprint series may be formed many times during a day of the dinosaur’s life. This can result in thousands of individual imprints known as “track.”

It is easy to see why fossilized dinosaur foot tracks vastly outnumber occupied dinosaur skeletons in the fossil record. Nevertheless, abundance does not guarantee clarity. Each footprint contains evidence of an animal’s foot shape, how it moved, how fast it moved, and the condition of the surface at the time of movement.

Erosion and distortion compound the uncertainty of the resultant tracks. The debate regarding the correct track maker can, therefore, last for years as well.

Why Three Toes Cause Big Problems

Dinosaur footprints with three toes are often confused with one another and are collectively referred to as tridactyl tracks. This was true of both carnivorous theropods and herbivorous ornithopods. Dinosaurs such as Tyrannosaurus, Iguanodon, Hadrosaurus, and Albertosaurus all had footprints with three functional toes.

Therefore, when a three-toed print is found in rock, it is usually not possible to determine which dinosaur made that print based solely on the print’s shape.

Since the 1800s, paleontologists have used experience and judgment, as well as comparisons, to classify tracks. However, the process has been limited by biases that develop over time. Previous machine learning studies on dinosaur footprints used supervised systems to assist in classification. In those studies, researchers labeled tracks before training computers to repeat those decisions. If the labels were wrong or uncertain, the models learned those incorrect labels as well.

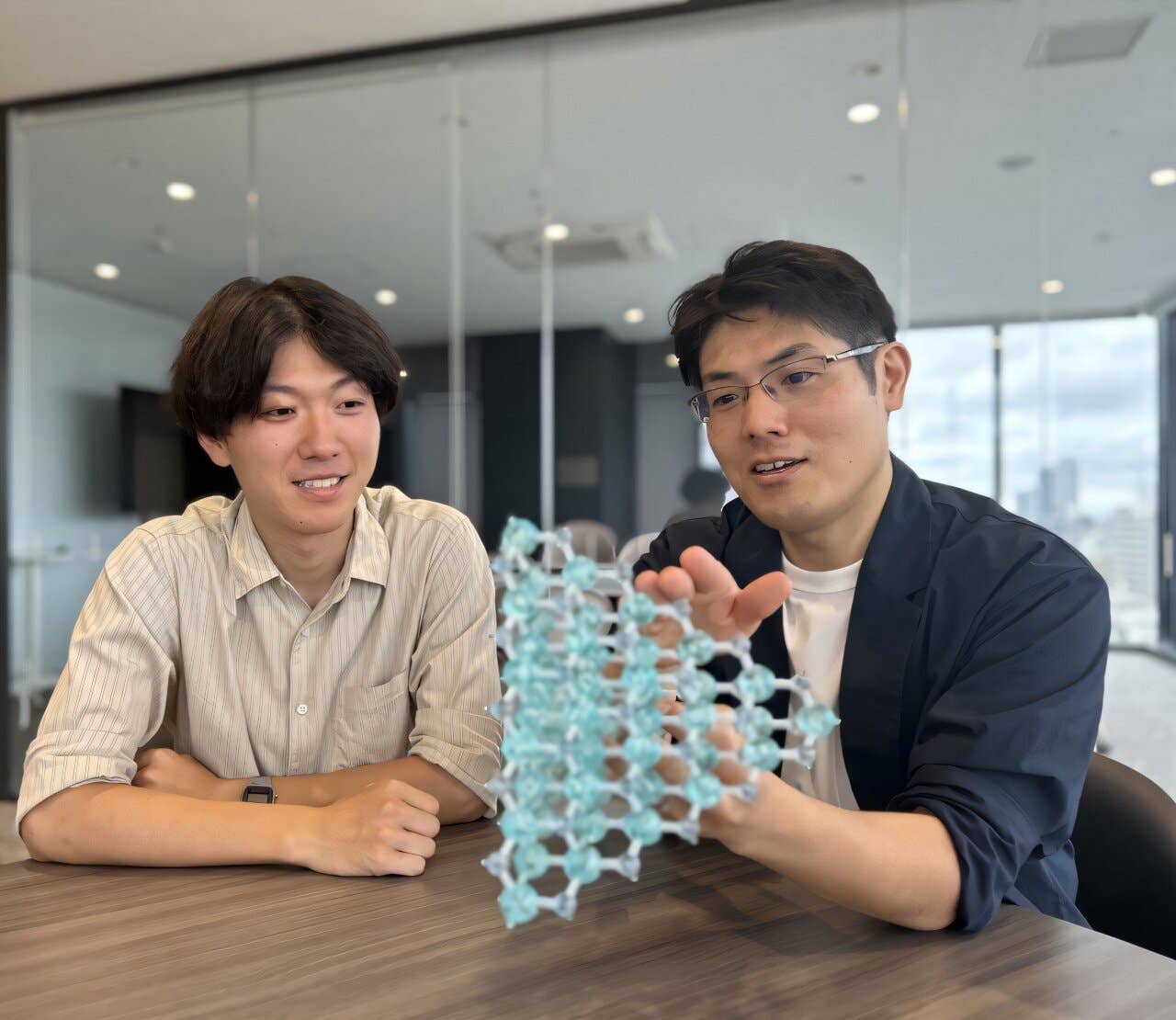

Hartmann questioned whether a different approach would be beneficial. While reading The Rise and the Fall of the Dinosaurs to his young son, Julius, he considered whether tools used in photon science might also be applicable in paleontology. Upon contacting Brusatte, the author of the book, he established an unlikely collaboration.

Allowing the Computer to Continue Learning

"Our team created an unsupervised neural network capable of identifying dinosaur tracks without knowing which dinosaur made a particular track. The network was initially trained on 1,974 actual footprints. These included tracks from extinct dinosaurs and modern birds," Hartmann told The Brighter Side of News.

"Data augmentation was performed by generating millions of altered versions of the original footprints. The augmentations were created using rotational transformations, stretching, and slight shape modifications," he added.

The researchers used a disentangled variational autoencoder (VAE) to compress each footprint into a lower-dimensional internal representation and then reconstruct it. This process forced the network to identify the most important features for classification. By evaluating multiple settings of the VAE parameters, the researchers established a balance between preserving detail and allowing clear interpretation of the VAE output.

Most importantly, the discovered patterns were generated without human input. The network identified eight major features that accounted for most of the variation in the classification scheme. These included overall shape, total load, toe spread, heel position, and weight distribution across the foot. Afterward, the researchers compared the results with expert classifications.

The agreement was found to be high. Between 80% and 93% of the tracks grouped together by the VAE were also identified by experts as belonging to the same general category. This level of agreement supports the conclusion that the VAE system is identifying meaningful biological signals rather than noise.

AI Reading and Mapping Dinosaur Footprints Over Time

To illustrate the interactions between the eight identified features, the researchers plotted all dinosaur footprints into a two-dimensional morphospace. This approach grouped similar footprints together. Quadrupedal dinosaurs, such as sauropods and stegosaurs, formed a distinct cluster, while modern and fossil birds formed two partially overlapping clusters.

Theropods, such as Tyrannosaurus, and ornithopods, such as Hadrosaurus, formed a highly overlapping cluster. This overlap has been the subject of debate for more than half a century. Although these groups show similarities, they also display differences in size and morphology.

Most disputed Middle Jurassic footprint records from Scotland clustered more closely with theropod dinosaurs than with ornithopods. In contrast, some controversial ornithiform, or bird-like, footprints showed a closer association with birds rather than nonavian dinosaurs.

Another long-standing question involves small, bird-like footprints from the Late Triassic and Early Jurassic. If these footprints were made by birds, they would place birds approximately 60 million years earlier than body fossil evidence suggests. In this study, most of these footprints fell within the bird region of the morphospace. This supports the interpretation that they were made by birds rather than other vertebrates.

Researchers caution that similar morphology can result from similar locomotion or from animals moving across wet surfaces. Only body fossil evidence can ultimately establish an accurate evolutionary timeline for the organisms associated with footprints.

From Research Tool To Publicly Available Application

The team’s intent to develop a user-friendly resource for the paleontological community led to the creation of DinoTracker. This application allows users to upload an image of a footprint, trace its outline, and compare it with a dataset of existing footprints. DinoTracker then provides information about the most similar footprints and identifies which shape features contribute most to that similarity.

DinoTracker does not claim to provide definitive answers. One major limitation is that footprint outlines must be created manually, which introduces error. Additionally, DinoTracker focuses only on two-dimensional shape and cannot account for depth or fine surface details.

Nevertheless, DinoTracker provides a useful platform for experimentation and independent data exploration. It offers researchers a way to confirm or challenge footprint classifications. For students and others interested in scientific reasoning, it also provides an opportunity to observe the scientific method in action.

Research findings are available online in the journal PNAS: Earth, Atmospheric, and Planetary Sciences.

Related Stories

- Fossil tracks in Italy record a turtle stampede from 80 million years ago

- Dinosaur tracks reveal mixed species travelled together in herds like modern mammals

- Decades old T. rex debate ends with stunning discovery

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.

Shy Cohen

Writer