Archaeologists find Europe’s oldest known blue pigment use

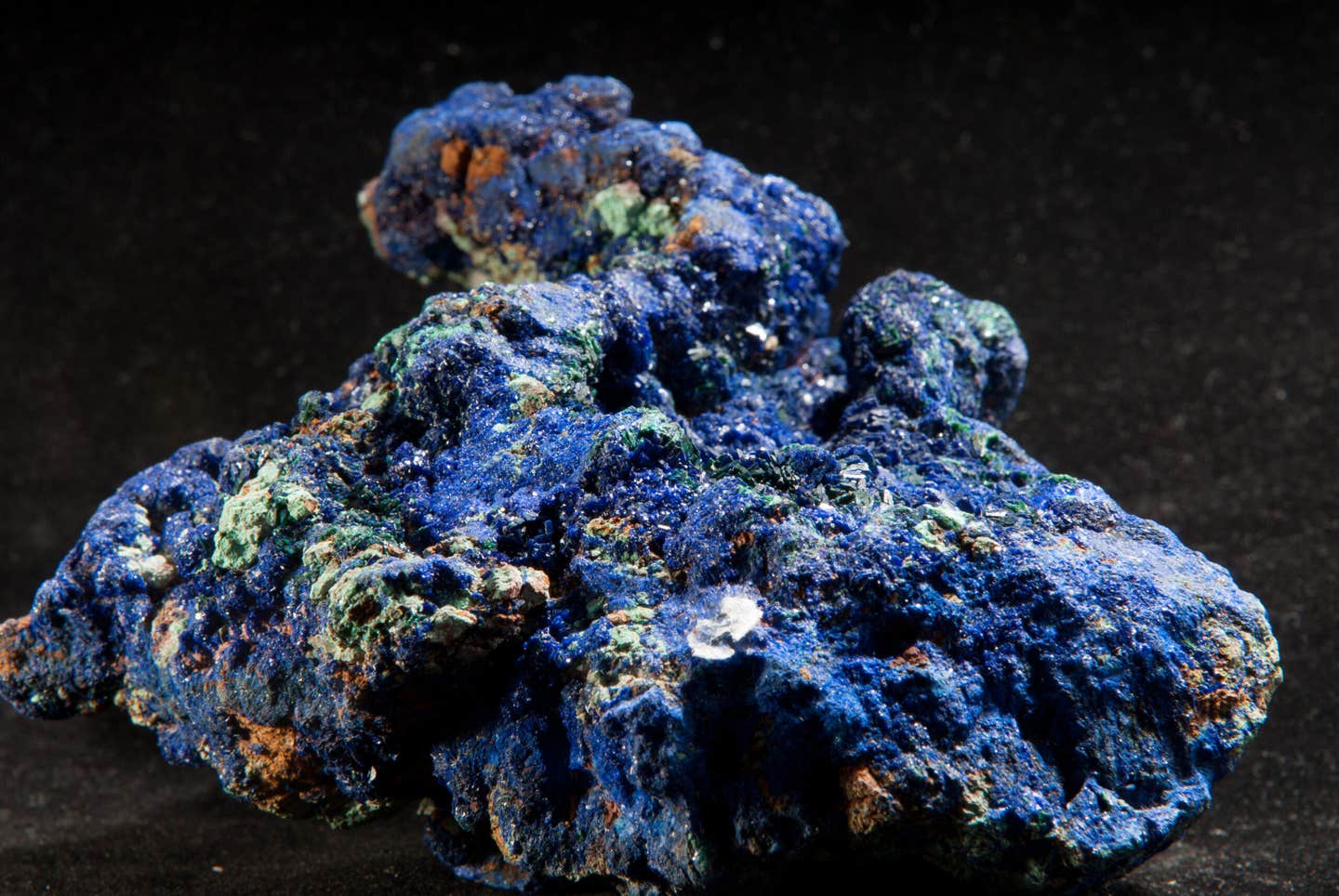

Aarhus University confirms azurite on a 13,000-year-old stone, the first known Palaeolithic blue pigment use in Europe.

Azurite traces on a Final Palaeolithic stone from Germany suggest Ice Age people used blue pigments, likely on skin or fabrics now lost. (CREDIT: Shutterstock)

A smudge of blue on an ordinary-looking stone has forced archaeologists to rethink what Ice Age people in Europe could see, make, and value. At the Final Palaeolithic site of Mühlheim-Dietesheim in Germany, researchers from Aarhus University identified traces of azurite, a vivid blue mineral pigment, on a stone artifact dated to about 13,000 years ago. It is the first confirmed evidence of azurite use in Europe’s Palaeolithic period, a time when scholars long believed artists relied almost entirely on red and black.

“This challenges what we thought we knew about Palaeolithic pigment use”, said Dr. Izzy Wisher, lead author of the study.

The find may sound small, but it carries a big message. The color blue has been essentially absent from the surviving art of this era. That absence shaped a story that Palaeolithic people either lacked access to blue minerals or did not find them appealing. The new evidence suggests a different possibility: blue existed in their world, but it may have lived on skin, cloth, or other perishable materials that rarely survive.

A Stone That Quietly Held a Secret

The artifact comes from Mühlheim-Dietesheim, a Final Palaeolithic site associated with the last stretch of the Ice Age in Europe. The stone itself is not a cave wall or a carved figurine. It is a functional object, the kind of item that can sit in a museum collection for years without raising alarms.

For a long time, the stone was thought to be an oil lamp. Its form appeared consistent with something used to hold fuel and feed a flame. But when researchers took a closer look, they noticed a blue residue on the surface. That faint coloration, easily missed by the naked eye, prompted a deeper investigation.

"Our research team did not assume the material was pigment. They treated it as a mystery. They used multiple scientific approaches to confirm what it was, and to rule out contamination or later staining. The suite of analyses identified the residue as azurite, a copper-based mineral known for its strong blue hue," Wisher told The Brighter Side of News.

"The color matters as much as the chemistry. Azurite is not a vague bluish tint. It is a striking, recognizable pigment, the kind of blue that can stand out against skin or fabric and carry meaning beyond decoration," she continued.

What Makes Azurite So Important

Before this discovery, Palaeolithic pigment use in Europe was typically framed in a narrow palette. Red ochres and black carbon-based pigments dominate well-known artworks and decorated objects from the period. The scarcity of other colors helped support the belief that Ice Age communities either did not have access to different minerals or preferred the bold contrast of red and black.

The azurite traces overturn the certainty of that view. The pigment’s presence suggests that Palaeolithic people could access a broader range of minerals than previously recognized. It also hints that their choices were deliberate.

“The presence of azurite shows that Palaeolithic people had a deep knowledge of mineral pigments and could access a much broader colour palette than we previously thought, and they may have been selective in the way they used certain colours”, Wisher said.

That last point, selectivity, is crucial. If blue pigments existed but rarely appear in durable art, it suggests the color may have been reserved for certain uses, or that it was applied to materials that did not last.

A Palette Hidden in Plain Sight

One reason the discovery lands with such force is that Palaeolithic evidence depends on what survives. Rock art lasts. Bone and stone tools last. Skin garments, woven materials, and painted bodies do not.

The researchers argue that the lack of blue in surviving Palaeolithic art does not necessarily mean blue was absent from Palaeolithic life. Blue may have belonged to activities that leave only faint traces: body decoration, dyeing fabrics, or marking organic items used in rituals and daily life.

If blue pigment was used on bodies, it could have signaled identity, belonging, status, or belief. A color applied to skin can be intimate and powerful. It moves with the person, changes in different light, and communicates without words. If it was used for textiles, it could have transformed clothing into a statement, especially in a world where many materials were earthy in tone.

The stone artifact helps make that invisible world a little more visible. If it served as a mixing surface, it points to a process. People did not just find a blue stone and admire it. They prepared it. They handled it. They likely combined it with something, perhaps to make it spread, last, or adhere.

From “Lamp” to Pigment Palette

The discovery also changes how researchers interpret the object itself. The stone was once categorized as a lamp. But the new evidence suggests it functioned more like a palette or mixing stone used to prepare pigment.

That shift matters because it suggests an organized practice. A palette implies repeated use and a controlled method. You mix. You adjust. You apply. A palette also suggests that color work could be part of a broader toolkit, even if the final painted surfaces are gone.

It also raises the chance that other museum artifacts may hold similar clues. A stone can look plain, yet carry microscopic residues that modern methods can identify. That means some of the “missing” evidence of early color use might not be missing at all. It may simply be unrecognized.

A Team Effort Across Disciplines

The study was carried out with a wide group of collaborators. It involved researchers at the Department of Geoscience at Aarhus University, including Rasmus Andreasen, James Scott, and Christof Pearce. It also included Thomas Birch, affiliated with both the Department of Geoscience at Aarhus University and the National Museum of Denmark, along with colleagues from Germany, Sweden, and France.

That mix of archaeology and geoscience was essential. Identifying pigments demands both cultural context and mineral expertise. The finding sits at the intersection of human behavior and the materials of the Earth, which is exactly where the story of early pigment use belongs.

What This Discovery Suggests About Ice Age People

The azurite traces add depth to the picture of Final Palaeolithic communities. They suggest people who paid attention to the visual world and had the knowledge to manipulate it. They also suggest that symbolism could be richer than the surviving cave walls imply.

Even a limited use of blue would speak to creativity and intention. It would mean someone noticed a mineral’s color, understood it could be processed, and decided it was worth the effort. It would mean that color, like toolmaking, involved skill passed through time.

It also adds a new dimension to how archaeologists think about expression in prehistory. If blue pigments were used in ways that disappeared, then many parts of Ice Age identity may be hidden from view. The things people did to decorate themselves, to mark life events, or to show social ties may have been more vivid than the brown and gray of surviving stone.

Practical Implications of the Research

This discovery encourages archaeologists to look again at existing collections with newer tools and sharper questions. Many artifacts excavated decades ago were classified based on shape and wear alone. If residues such as pigments remain on surfaces, modern analysis can reveal uses that were previously invisible. That could expand knowledge of how early humans used color, not only in art but also in daily life and social rituals.

The findings also broaden how researchers approach ancient creativity. Instead of judging the past only by what remains on cave walls, scientists may place more focus on perishable practices such as body decoration and textile coloring. This can lead to richer reconstructions of human identity, belief, and social organization in the deep past.

Finally, the study underscores how interdisciplinary research can reshape history. When archaeology teams work closely with geoscientists, they can connect human choices to specific materials and landscapes. That improves how researchers understand cultural knowledge, trade or travel for resources, and the development of symbolic behavior over time.

Research findings are available online in the journal Antiquity.

Related Stories

- Scientists engineer microbe that mass-produces camouflage pigment

- Breakthrough new treatment developed for retinitis pigmentosa

- Color-coded mosquitoes safely enables male-only releases to combat Dengue and Zika

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.

Rebecca Shavit

Writer

Based in Los Angeles, Rebecca Shavit is a dedicated science and technology journalist who writes for The Brighter Side of News, an online publication committed to highlighting positive and transformative stories from around the world. Her reporting spans a wide range of topics, from cutting-edge medical breakthroughs to historical discoveries and innovations. With a keen ability to translate complex concepts into engaging and accessible stories, she makes science and innovation relatable to a broad audience.