Deep magma oceans generate magnetic fields to protect planets and support life

Molten rock deep inside super-earths may generate powerful magnetic fields, reshaping ideas about planetary habitability.

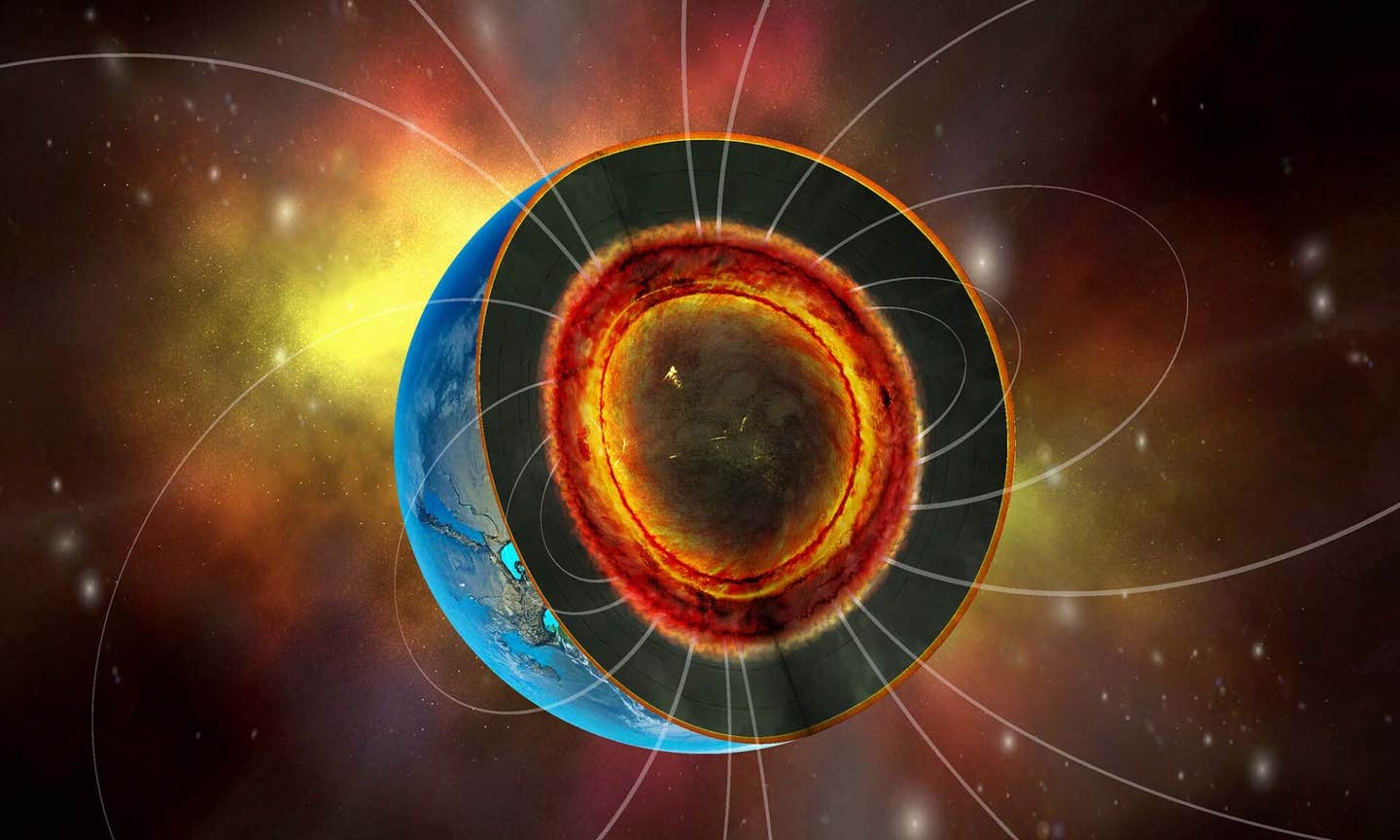

Deep layers of molten rock inside some super-earths could generate powerful magnetic fields—potentially stronger than Earth’s—and help shield these exoplanets from harmful radiation. (CREDIT: University of Rochester Laboratory for Laser Energetics illustration / Michael Franchot)

In addition to shaping the interior of rocky planets, molten rock located deep within these planets may also contribute to the creation of a planet’s magnetic fields, which protect the entire planet from radiation.

This latest discovery by scientists from the University of Rochester has shown that a basal magma ocean (a layer of molten rock) located deep within a planet may produce a long-lasting magnetic field around it. Large rocky exoplanets called super-Earths may benefit from this long-lasting magnetic field.

Magnetic fields protect the atmosphere and surface of planets from charged particles as well as cosmic radiation; therefore, they play an essential role in protecting life on planets. Our planet, Earth, has a magnetic field produced by the movement of liquid iron in its outer core; however, many rocky planets, including Mars and Venus, do not have global magnetic fields at this time because the physical conditions in their cores do not support the same processes that create our magnetic field.

Miki Nakajima, an associate professor in the Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences at the University of Rochester, describes how a strong magnetic field is vital for supporting life on a planet: “Most of the terrestrial planets that exist in the solar system, such as Mars and Venus, do not have global magnetic fields because their cores don’t contain the necessary conditions to generate a magnetic field.”

Why Super-Earths Matter

Super-Earths may be the exception, where conditions are harmonious with the formation of magnetic fields. Super-Earths are defined as planets larger than Earth but smaller than the gas giants like Neptune. They are not necessarily Earth-like; super-Earths simply refer to their size and mass, and many of these super-Earths are rocky with solid surfaces rather than being covered in a thick layer of gas.

While super-Earths are some of the most common types of planets found in our galaxy, none belong to our solar system, and they possess significantly greater internal pressure than Earth due to their size. Because of these greater pressures, large volumes of deep mantle rock can remain in a molten state for many billions of years.

Many of these super-Earths also orbit within the habitable zones of their stars, where the presence of liquid water on their surfaces is possible. Studying the interior structure of these planets will enable scientists to evaluate whether they are stable enough to have retained their atmospheres and possibly even support life.

"Our research team studied the presence of a basal magma ocean—a body of molten or partially molten rock residing at the bottom of the mantle, above the core. Early in Earth’s history, there was likely a basal magma ocean in place after the Moon-forming impact," Nakajima told The Brighter Side of News.

"However, on the larger super-Earths, this basal magma ocean may be present for much longer periods of time," she continued.

Recreating Planetary Interiors on Earth

In order to create the extreme conditions of super-Earth interiors for study, Nakajima and her team utilized a combination of laboratory experiments, quantum mechanical modeling, and planetary evolution modeling to achieve their results. The laboratory-based experimental work was conducted at the University of Rochester’s Laboratory for Laser Energetics (LLE) using the OMEGA EP Laser System.

To recreate the extreme pressures and temperatures present deep in a super-Earth, researchers used intense laser-generated shock waves to subject samples of molten rock to pressures and temperatures many times higher than those found within Earth’s core–mantle boundary.

Ferropericlase—a mineral composed mostly of magnesium oxide with a small proportion of iron—was chosen for this research because it is the closest analogue of the rock in the super-Earth mantle. Three different compositions of ferropericlase, from 100% magnesium oxide to 5% iron, were investigated.

The aim of these experiments was to determine the degree to which molten rock is electrically conductive under extreme environmental conditions. Additionally, knowing the electrical conductivity of materials such as molten rock will help us understand how the ability of a fluid to move creates a magnetic field through the dynamo effect.

What the Experiments Revealed

As pressure was increased on the molten rock sample, the measured electrical conductivity of the molten rock increased significantly more than what had been previously predicted. At the highest levels of pressure, the measured electrical conductivity of the molten rock sample was sufficient to generate a strong magnetic field.

The addition of iron had very little effect on the measured electrical conductivity of the molten rock samples.

Previous theoretical models had suggested that adding iron to molten rock would considerably increase its electrical conductivity, making it highly conductive. However, the experimental results demonstrated that magnesium oxide by itself becomes highly conductive when subjected to the high pressures resulting from increased pressure on the mantle. Under these conditions, the contribution of iron to increased electrical conductivity became negligible.

For the samples that did not contain iron and for those that did contain iron, there was no statistically significant difference in the measured electrical conductivity. The experimental results agree with results obtained from advanced computer simulations based on quantum mechanics.

“This research was a very exciting and challenging experience for me because my background is mostly computational, and this was my first experience doing experimental work,” Nakajima said. “I am very grateful to my collaborators across the spectrum of research disciplines who supported me in this interdisciplinary research.”

Rethinking Planetary Dynamos

This research raises many questions about how Earth produces its magnetic field through a process called guidance and how, through convection generated by heat and chemical changes in the outer core, Earth generates the magnetosphere.

Additionally, since there is evidence that Earth’s inner core is relatively young, what role will the growing inner core have on the movement of heat and light elements? Earth has a magnetic field today, but paleomagnetism shows that it had one as long ago as 3 billion years before the formation of an inner core that may have contributed to its size.

In the absence of a physical mechanism to explain how early magnetic fields were produced, scientists hypothesize several possibilities, such as thermal convection only, gravitational influence from the Moon, or the chemical differentiation of materials in Earth’s core.

A new theory has been proposed for the production of an early magnetic field: it was generated from the intense motion of molten rock within Earth’s mantle.

When large amounts of molten rock exist within the mantle, power can be produced from the motion of this material through the same physical processes as a dynamo powered by a conductor, such as a molten metal mass. The only requirement is that this molten rock must have a very high magnetic Reynolds number, which means that it can produce magnetism faster than the magnetism dies away due to the normal processes of diffusion.

When Molten Rock Can Create a Magnetic Field

The researchers studied experimental data and constructed experimental data models to determine when the conditions present in a basalt magma ocean will create a high Reynolds number. The results of this study depend on the size and internal structure of the planet.

For planets with at least three times the mass of Earth and with a relatively large core, the present conditions would support a higher conductivity for a dynamo.

In some theoretical models, a magma ocean dynamo will last longer than a dynamo driven by the inner core. The reason for this is that a magma ocean sits closer to the surface of a planet than Earth’s core, resulting in a larger surface magnetic field being produced.

A theoretical six–Earth-mass planet was modeled, and it was found that a magma ocean-driven magnetic field would likely dominate during the majority of the planet’s existence. This implies that a dynamo created by both the inner core and the molten lava ocean will have ceased to operate only after a few billion years.

The researchers also studied small bodies, such as young exoplanets that contain a magma ocean on their surface or bodies heated by tidal forces or intense starlight. These small bodies also possess a high magnetic Reynolds number and can briefly produce magnetic fields depending on the conditions.

Practical Implications of the Research

The research findings have provided new insight into how scientists currently view the generation of magnetic fields on rocky planets. A planet’s ability to prevent electrons and charged particles from striking its surface was thought to depend only on the presence of an iron core.

The presence of a hot, moving body of molten rock below the surface of a planet can significantly impact its ability to provide this type of protection to its surface. Thus, it has expanded the set of worlds that can be classified as possibly habitable in the search for exoplanets.

Historically, planets that had excessive erosion due to radiation and weathering were typically thought to be unable to retain a stable atmosphere. However, the study has shown that planets that can successfully produce long-lived magnetic fields from molten rock are also candidates for sustaining life.

In terms of guiding future observations, the research findings provide new ways for astronomers to test the magnetic fields of newly discovered exoplanets. When studying the first detected magnetic fields of newly discovered exoplanets, these results will help guide astronomers in their predictions concerning the strength of super-Earths.

Finally, the conclusions of this research will enable scientists to develop a better understanding of how planets evolve and the conditions required for the emergence of life-friendly environments throughout the universe.

Research findings are available online in the journal Nature Astronomy.

Related Stories

- Two hidden continents above Earth’s core may be relics of a primordial magma ocean

- ‘Slushy’ magma ocean led to formation of the Moon’s crust

- Oceans in the fire: How magma and hydrogen forge massive quantities of planetary water

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.

Joseph Shavit

Writer, Editor-At-Large and Publisher

Joseph Shavit, based in Los Angeles, is a seasoned science journalist, editor and co-founder of The Brighter Side of News, where he transforms complex discoveries into clear, engaging stories for general readers. With vast experience at major media groups like Times Mirror and Tribune, he writes with both authority and curiosity. His writing focuses on space science, planetary science, quantum mechanics, geology. Known for linking breakthroughs to real-world markets, he highlights how research transitions into products and industries that shape daily life.